What’s a covered strangle? It’s a three component trade made up of long stock, selling an out of the money call, and selling an out of the money put. It’s a high probability trade that is less volatile than owning all stock, but uses a lot of capital keeping returns somewhat limited. It’s a great way to ease into strangles, which typically are reserved for very experienced traders. It can be traded in almost any account because it only requires Level 0 option permission approval, so most retirement accounts will even allow it.

Technically, a covered strangle is a combination of a covered call and cash secured put, two strategies that are a favorite of many conservative option traders. It’s “covered” by stock on the call side and cash on the put side. Let’s say we have 100 shares of the SPY ETF trading at $400 per share, a value of $40,000. We can likely sell a 420 strike call a month out for about $2.00 premium or $200 total for the 100 share contract. If we have another $38,000 cash in our account, we can sell a 380 strike put for around $4.00 premium or $400 for the contract. We’ll likely collect a little around 1.5% of our capital at risk. We have $40,000 in stock and $38,000 in cash securing our strangle. We can hold to expiration and let the chips fall where they may, or my preference of managing early and rolling out for more credit.

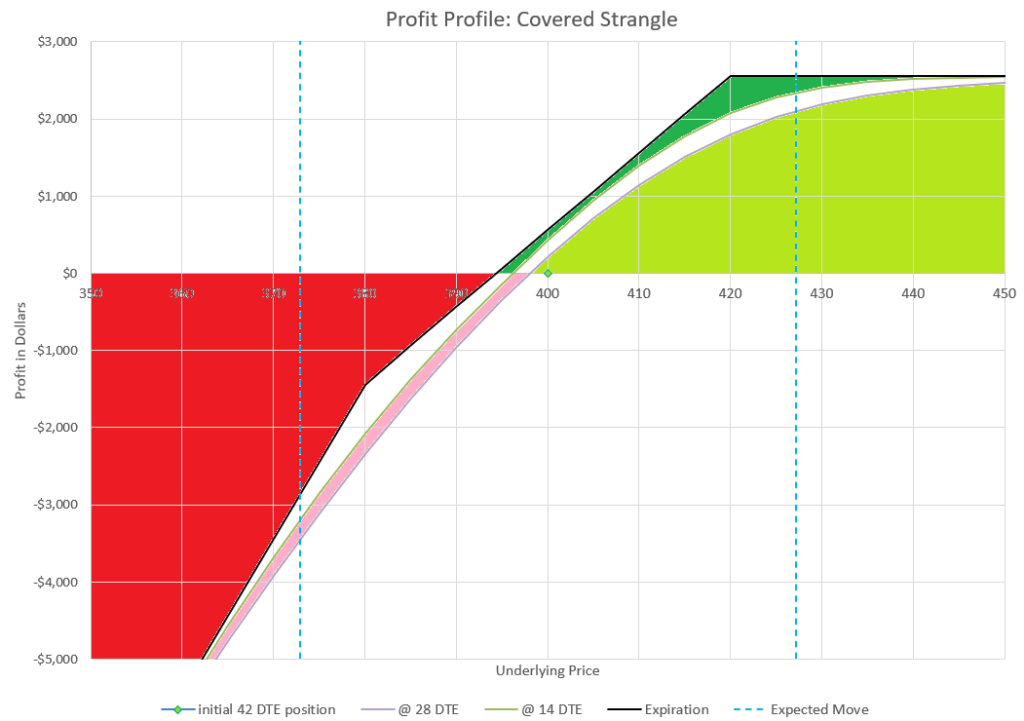

A trading friend has been talking up covered strangles to me for years. Honestly, I’ve looked past it as it seemed like a boring trade that takes a lot of capital for a somewhat small return. At first glance, there’s limited upside because gains are capped by the call, and unlimited (to zero) downside. If the stock price goes up, the call can be triggered and the stock sold for the call strike price. If the stock price goes down, the stock and the put both lose value. And we are doing this for a 1.5% return on capital? And this is supposed to be a good conservative trade? Actually, yes! Let’s dig a little deeper and see why.

Probabilities, Volatility and Manageability

There are three major factors that make this trade desirable. First, there is a better than 50% probability that this trade will deliver a profit. Second, this position is significantly less volatile than being fully invested in stock. And finally, strangles are one of the most forgiving trades to manage, allowing continual repositioning, or a variety of other trade variations if held until expiration or assignment. As a bonus benefit, we are invested in stock, often with dividends, and over time the market tends to go up for a gain. Let’s review each benefit in detail.

Probabilities of Profit

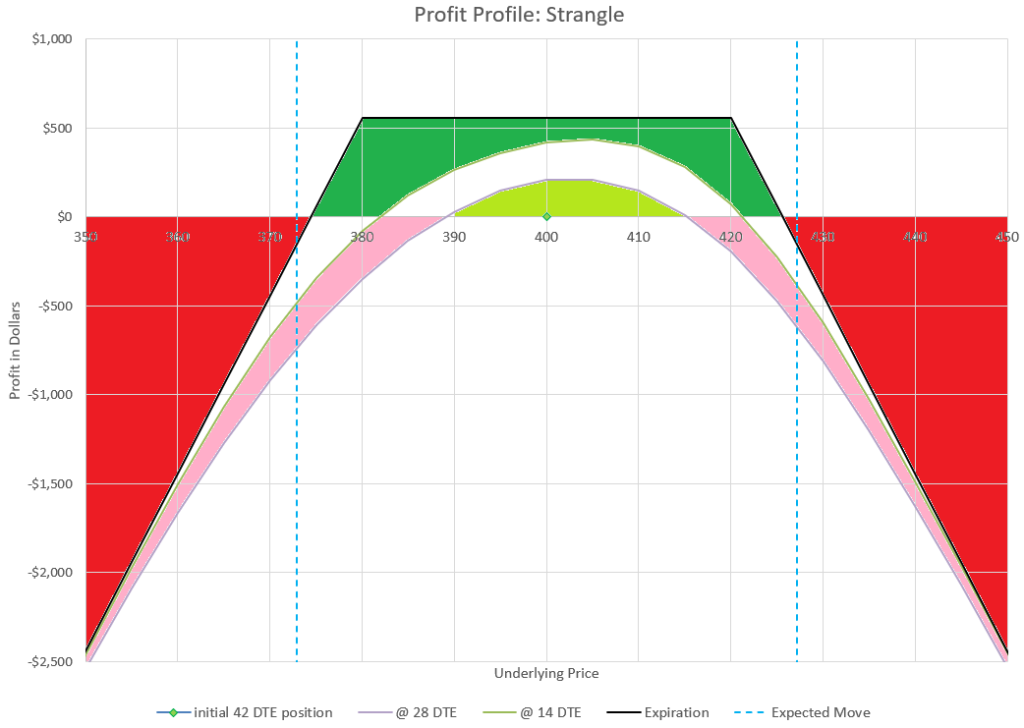

If we look at our example trade mentioned earlier, let’s assume that we are selling a 20 Delta put and a 20 Delta call. We can quickly see that if held to expiration, there’s a 40% chance of one of the options expiring in the money- 20% for the call, and 20% for the put. If the concept of Delta matching percentages is new to you, refer to my webpage on Delta. But even if an option ends up in the money, it doesn’t mean the trade loses. We can look at it from just the stock, just the strangle,or the full covered strangle.

The stock itself is a slightly better than 50/50 proposition. On average, we expect to see a bit better than 0.5% return per month. But that’s on average. Our expected move for a month tends to average about 4%. (See the page on Expected Move if this is a new concept.) So, a lot of up months and a lot of down months, but we also expect the stock to stay inside the strike prices of the options sold. Historically, our monthly probability of profit is between 55 and 60%. Individual stocks may have somewhat different probabilities than indexes, but most are in this range.

The strangle of a short put and short call have well defined probabilities. While the probabilities of ending in of the money are 40% at expiration, we also have to consider that we have collected premium that gives us an additional cushion before we actually lose money. In our example, we have collected $6 premium and have strikes $20 away from the current price. We don’t lose money at expiration until the stock price ends up over $26 away from our starting price. A quick check of options Deltas will show that we have about a combined 25% probability to expire over 26 points away from our starting price, so we have a 75% probability of at least some profit from the strangle. If we manage early, we can improve this probability to an even higher rate, reducing the possibility of an outsized move blowing through our strikes.

If we do some basic math, the average probability of the stock and strangle would be a little better than 65%, based on our probabilities of each part of the trade. But there’s a little more subtlety to probabilities of the covered strangle, due to the interaction of options and stock. On the upside, we could be assigned and have our stock called away if the market goes up more than 5%. We’d make $2000 on our stock plus keep the $600 option premium we collected, a $2600 profit on $78,000 capital, a 3.3% return. No matter how high the stock goes, our gain is capped at 3.3%. On the downside, our stock starts losing money immediately, but we still have our $6 premium collection that buffers our total position down from $400 to $394 before the covered strangle is at a loss at expiration. The put doesn’t add to the loss at expiration until it is in the money, but below that both the stock and the put lose equal amounts as the price declines. If we check the option table, we have somewhere around a 38% probability of our stock expiring more than $6 below our start price, so actually we have a 62% probability of profit for the full covered strangle.

If it wasn’t already clear, the covered strangle is a bullish trade. Up moves are always profitable, and the only way to lose is a market decline more than the total premium collected. That shouldn’t be a surprise, owning stock is bullish, a strangle is neutral, and the combo covered strangle is still bullish.

We’ve discussed in other posts that Delta actually overestimates moves and that probabilities are actually higher for profit, especially on the put side of the trade as put buyers buy up insurance to protect from big moves down. Since our risk is to the downside, our probabilities actually are a little better than Delta might suggest.

From this discussion, you can see that there are a number of ways to think about probabilities with a covered strangle. The takeaway should be that probability of profit is high. In a bit, we’ll talk about how management can help improve our odds even more. But first, let’s talk about how a covered strangle reduces portfolio volatility.

Portfolio Volatility Reduction

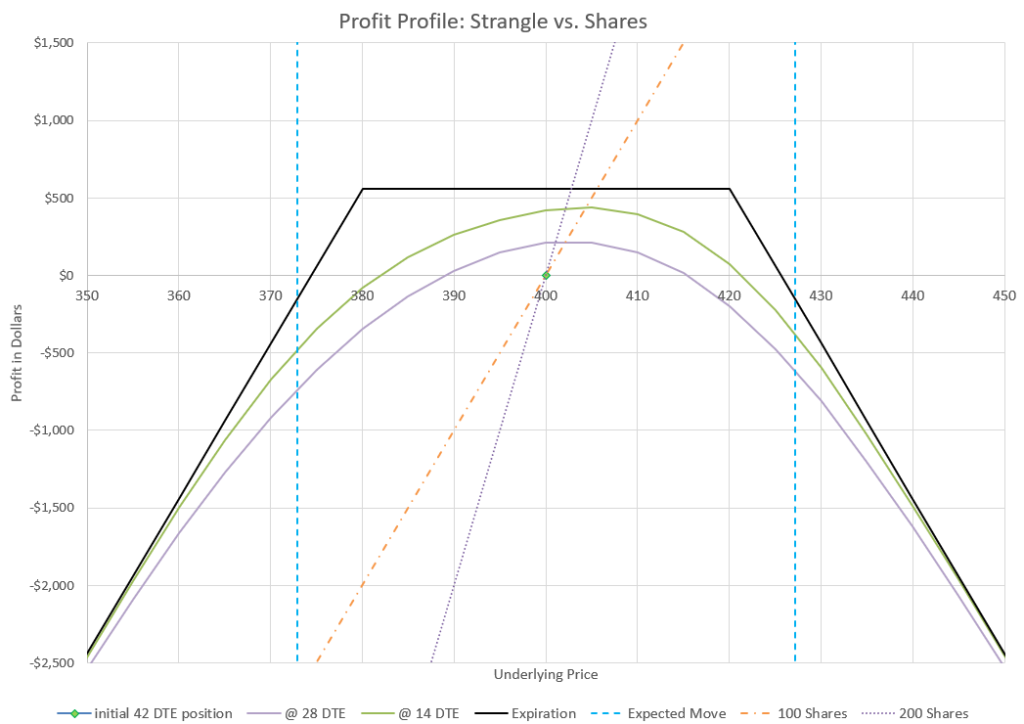

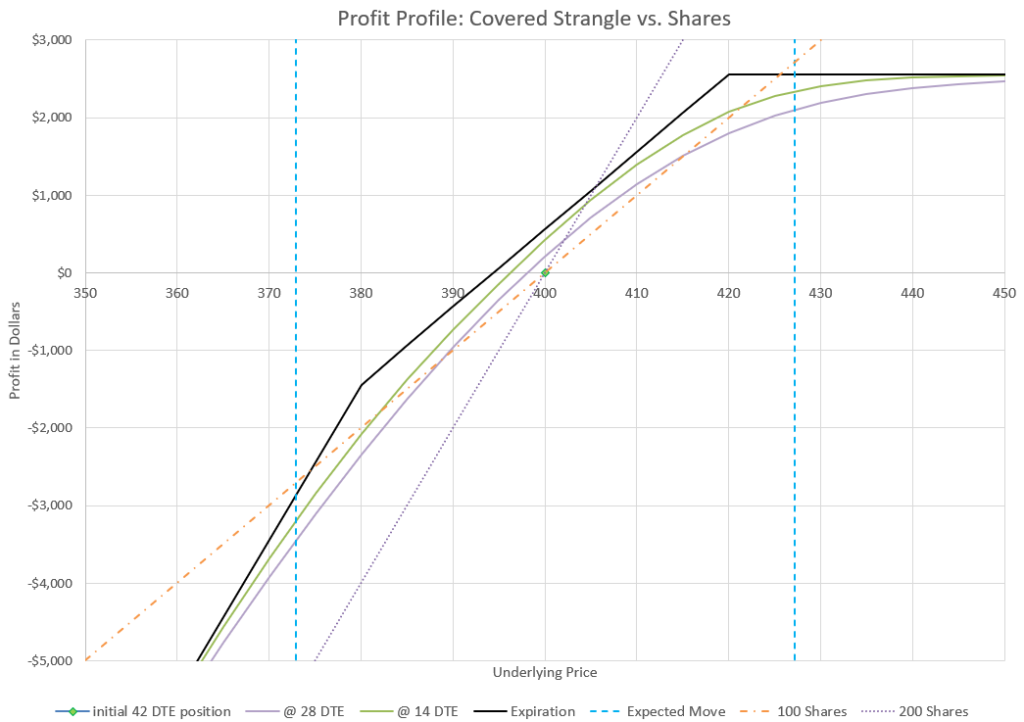

It should be somewhat obvious that when we combine a pure bullish strategy of owning stock with a neutral strategy of a strangle, we have a combined strategy that is somewhere in between. Let’s compare a covered strangle to being fully invested in stock.

Using Delta to represent equivalent stock (another way Delta can be used), 200 shares of stock has a 200 Delta value. A fully neutral strangle paired with 100 shares of stock has 100 Delta value. Both positions use the same capital, but the all stock position will move up and down twice as much day to day as the covered strangle. Delta will vary from neutral as the underlying price changes, reducing with price increases and increasing as prices go down. So, position volatility will go up if the underlying price declines, and vice versa. It should also be clear that the strangle and the stock behave differently, and that difference diversifies the price response of the covered strangle.

You might think that with a decrease in position volatility, we would be giving up a lot of potential return. But actually, we can expect as much as 0.5% average return per month from the strangle, about the same as the stock. But since one side of the covered strangle is likely to do better in each point in the trade, returns are likely to be more consistent than either by itself.

Managing Strangles

Of all option trades, strangles are about the most manageable of all strategies. Both the short put and short call can almost always roll out in time for a credit, whether the strike is in or out of the money. With spread type options, only out of the money strikes can collect credits from a roll. For single short options, there is no long strikes to buy back.

I like to use rolls to recenter my strikes around the latest prices. Going back to our example, if the underlying price went down to 390 after a couple of weeks, we should be able to roll our strikes out a few weeks more with 370 put and 410 call, and collect a credit. The idea is to use rolls out to just keep collecting credit. Compared to rolling spreads and iron condors, there’s way more forgiveness, and more likely profit even in moves that test the strike prices of either option. Sometimes, I may pay a debit on the tested side to move the strikes well out of the money, and collect a bigger credit on the untested side and move the strikes closer to the money when they are very far away. Even if my strangle position is showing a loss, I can usually still collect a credit and keep the trade alive and let time decay the increased premium.

My goal is to consistently collect credit from rolling the strangle as the underlying stock goes up and down. Using SPY at around $400 a share, I’ve recently found I can roll out weekly from around 25 DTE to 32 DTE and collect a $2 premium net credit, or about 0.5% of my cash secured capital. A year of that would be 25% return, which would make most conservative traders very happy. I can’t do that every week because sometimes a big move sends my positions into a tested area where I need to adjust strikes to recenter and the net credit is smaller.

Many traders don’t mind the assignment either way and happily wheel between covered calls and cash secured puts, but I like to try to keep both options of the strangle in this situation if I have the capital available to support a position. The strategies aren’t that different, but with a covered strangle, I can adjust easily no matter which way the market goes, and not have to buy and sell my shares of stock.

Assignment due to dividends is a possibility, which I find as a minor annoyance, but actually manageable. Remember that the calls are covered, so worst case when a stock goes ex-dividend and is close to being in the money, it will get called away. Then, a trader can use the wheel strategy and sell a put to get the shares assigned back. I avoid this by adjusting strikes so my calls are far enough out of the money that it never makes sense for an assignment to occur. I also don’t hold options that are near expiration and most likely to get assigned, especially at dividend time. But again, since the calls are covered, there is no real risk, just the selling of shares for a profit.

Level 0 Strangle?

Brokers have different levels of option trading permissions. I’ve written about this in my pages on different levels of risk and comparing risk. Level 0 is the lowest level of risk and easiest for a trader to be permitted. Most brokers consider covered trades as Level 0, although some brokers may have a different name for it. The reason most consider this option permission level as zero is because it is actually less risky than holding the same amount of stock, whether the position is a covered call, a cash secured put, or a covered strangle. That means less risk for the broker and for the trader. This makes covered option trades a favorite of conservative traders.

Since we are talking about strangles, how different is the risk of a covered strangle from a margined and naked Level 3 strangle, or a futures option naked strangle? The big difference is that there is nothing covering the risk in either direction with higher risk levels of strangles. There is absolutely no limit to the risk to the upside. Prices can keep going up, and a naked short call keeps losing no matter how high prices go. On the downside, most brokers only require around 20% of the capital at risk for a trade to be executed. So losses can greatly exceed the initial capital in a big downturn. In contrast, a cash secured put can’t lose more than the cash required at the start of the trades, because 100% of the value of the stock that would be assigned at the strike price has to be in the account. The highest strangle risk is from using naked futures options which utilize SPAN margin, and even less capital required, which also means even more potential for crazy losses if the market gets out of hand.

Because Level 0 covered strangles have several times less risk than naked Level 3 strangles, they provide a great way to get used to trading strangles. Traders can get familiar with the mechanics of strangles without the risk of naked positions. And covered strangles are still a viable way to make a return on investment that often beats the market, particularly in flat and down years.

I’ve written about different types of underlying securities, but covered strategies including covered strangles can only use stocks or ETFs, because a trader can’t own an index. Stocks and ETF are familiar to most all traders, and many aren’t even aware of index or futures options, so covered strangles mean nothing new to learn.

Probably the biggest issue for trading covered strangles is the amount of capital required. For my favorite ETF underlying, SPY, trading at $400 a share, the shares alone are $40,000 and selling a cash secured put ties up approximately another $40,000. So, for the smallest 1 contract increment of a covered strangle, a trader needs $80,000. For many traders, this is out of reach. A low priced stock might be more of a practical choice, so Ford Motor (F) trading recently at around $12 a share needs about $2,400 to get a covered strangle going.

Because individual stocks typically have more implied volatility than ETFs, there is more premium to collect, making individual stocks good candidates for covered strangles. Since the trade is covered and risk is slightly less than owning stock outright, it can be argued that covered strategies are best used with individual stock. Assignment is more likely in individual stocks because outsized moves are more likely, but the position is covered by cash and stock, so assignment is just a feature of holding a covered strangle. For traders who haven’t experienced assignment on a naked position or spread, assignment on a covered position is a much less stressful way to be introduced to the concept.

It may appear that I’m portraying the covered strangle as a beginner option strategy, but it is really a sophisticated method of reducing risk. Most people are scared of options because they are considered risky. The covered strangle is one strategy that uses options to reduce risk compared to owning equivalent shares of stock. Many conservative investors utilize covered strategies, not to speculate, but to lessen the volatility of their returns. Most financial planners will give you a deer-in-the-headlights look if you ask about this strategy even though it reduces risk and should be a common tactic. But most financial professionals are completely unaware of ways to use options to reduce risk. So for that reason alone, don’t ever think of covered option strategies, including the covered strangle, as a beginner strategy. I think of it more of a way to be fully invested and sleep better at night strategy.