Most discussions of options start with the Covered Call. The Covered Call can be done in almost any account, requires no extra capital if you own 100 shares of stock, potentially increases portfolio income, and reduces volatility of returns. What is not to like?

What is a covered call?

For those not familiar, a covered call is a trade where the owner of stock, sells a call for that same stock. This can also be done with exchange traded fund (EFT) shares. The risk of selling the call is “covered” by the shares that option owner has. The worst thing that can happen to the call position is that the stock price goes up and the call is exercised, and the shares are “called” away.

Let’s look at an example. Say we own 100 shares of a stock currently trading for $400 per share. We can sell a call with a strike price of $420 expiring in 6 weeks or 42 days for a premium of $2.00 and collect $200 (1 contract is 100 share times the premium). By selling a call, we agree to sell our 100 shares for $420 any time in the next 6 weeks if a call buyer exercises the option. We don’t have a say in it, only the buyer does. But, if it happens, we also keep the $2.00 premium we just collected, so the total profit would be $22 over the current $400 share price, a 5.5% gain in 6 weeks or less. More likely, the call option will expire worthless if we don’t do anything and we keep the $2.00 premium and the 100 shares. That’s the proposition, and the potential outcomes from holding until expiration. And most people who discuss selling covered calls end the discussion with that, but this site is written for data-driven option traders, so let’s dig in deeper.

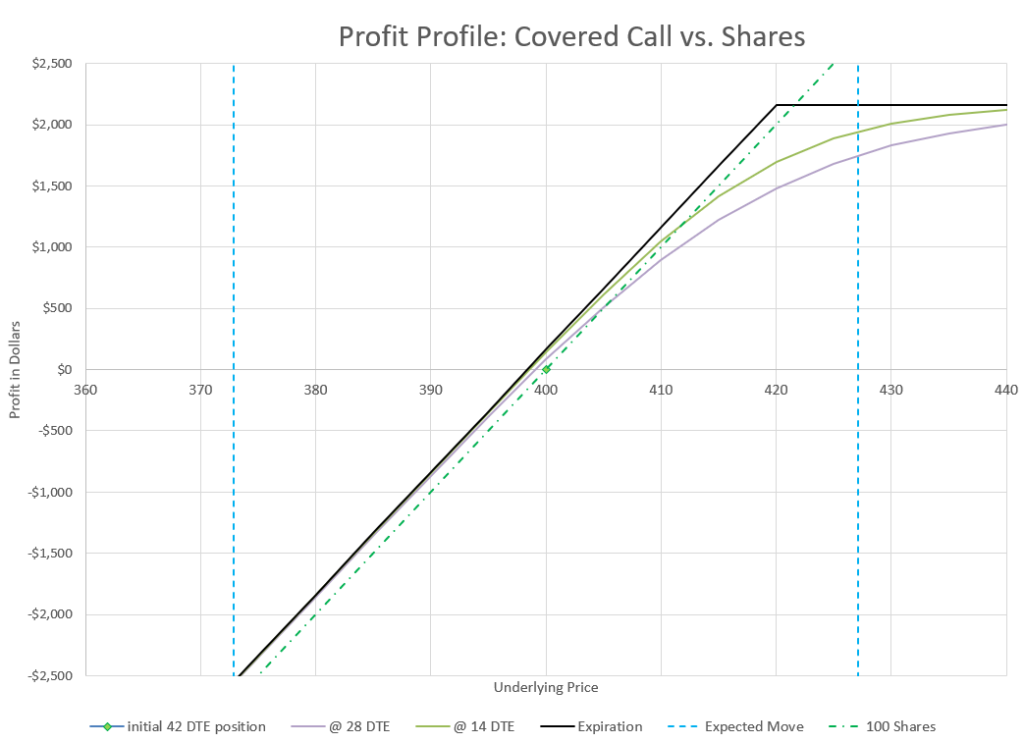

Below is a profit chart showing the profit profile at different points in time. One thing to notice is that the all the lines near the current price see to be close to parallel or tracking with the expiration profit and the profit from just holding 100 shares alone. Those two lines are parallel, with the difference being the $200 that was collected when the call was sold.

However, if we look closely the lines representing the value at 28 days and 21 days aren’t quite as steep. This is because the time value varies significantly over different underlying prices. Initially, the Delta of the call being sold is 0.20, signifying that its value will change by 0.20 for every dollar the underlying stock changes in price, and meaning there is a 20% chance it will expire in the money. I find it easier to think of the our Deltas in whole numbers representing 100 shares, so our 20 Delta calls that we sold combine with the 100 Delta of the underlying shares to give us a net Delta of 80. So initially, our total position is going to move up or down $80 for each dollar in price that our stock changes. That means our position is only 80% as volatile as owning stock outright.

Another thing to notice is that even after a few weeks, the position has a profit even in a small $1 decline in stock price and is ahead of stock alone for the first several dollars in price increase compared to owning stock outright. So, if the price doesn’t move much, we have a profit and a better profit than owning stock. This is a nice outcome when the market doesn’t move.

A big move down is still a big move down for our total position, we just lose $200 less than we would have if we hadn’t sold the call which is only a small consolation if the stock drops 10 or 20 percent. As the market goes up, the position makes money, but we have an upper limit based on the strike price of the call. A quick move up increases the Delta of the call and keeps the overall position value well away from the expiration value until we get to expiration. So, at big moves, we have virtually unlimited risk to the downside and limited profit to the upside, which seems a bit backward.

If you sell covered calls much, you’ll have a number of situations arise of extreme moves in one direction or the other that can be very frustrating. This situation really turned me off from this strategy for a long time until I focused into probabilities more and worked out my management strategies. Before we get into those, let’s break this trade apart to see how each component behaves individually and see how that might make you think twice about the strategy.

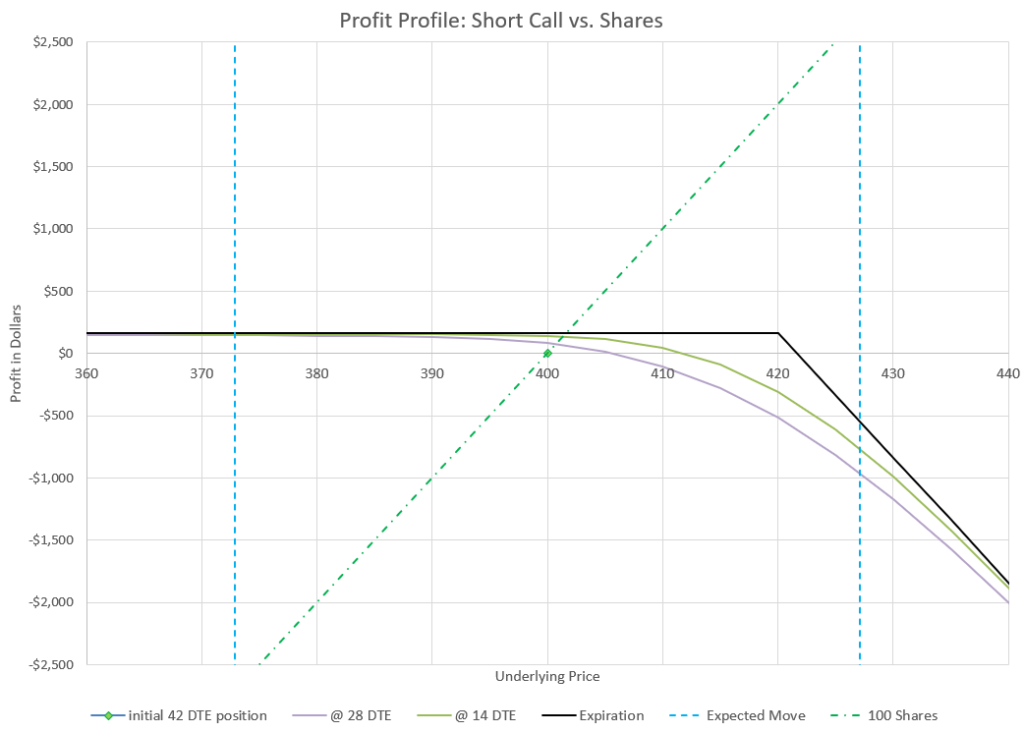

Anyone who isn’t a fan of the covered call can point to a graph like this to help explain what there is to not like about selling a call. The issue is that in a big up market the call can lose a lot of money- all the money that the stock is making, and that is money that is then gone through the short call. We could have had a big profit from owning stock, but now we don’t. Before we get to feeling too sorry for the trader in this situation, we need to back up and remember that we didn’t actually lose money, the trade is a profit, just not as profitable as if a call hadn’t been sold.

Particularly in bull markets, selling calls outright is often a losing strategy over time. Even though the trade has a relatively high probability of profit, the losses of the lower percentage of losers can be much bigger than the gains. Run backtests and it is hard to find a naked call selling strategy that is profitable over time. So, one might decide to skip the call selling and just stay long. But we are talking about covered calls, not naked calls, and the stock portion of the trade make a difference.

I’ve read lots of books and articles about how selling calls is like creating a bonus dividend on stock- make an extra 5-10% per year by selling calls on stock that you already own. The actual results would say that maybe with good management, a covered call seller will beat the buy and hold seller. Just don’t expect selling calls to be a get-rich-quick scheme. It isn’t.

What can be done to improve results of selling covered calls? First, we need to have a mindset to look at the true benfits of selling covered calls. Next, we need a toolbox of management strategies for dealing with the ups and downs of selling covered calls. And finally, we need realistic expectations of the type of results that can be achieved. If we do all these things, we’ll find selling covered calls to be a satisfying strategy.

Benefits of Covered Calls

Selling covered calls has three significant benefits-reduced volatility, additional income, and improved probability of profit. Let’s take them one by one.

Trading options can be used as a way to influence the volatility of the returns of a portfolio. Most people think that options are extremely risky, but it really is a matter of how they are used. Selling covered calls is a way to reduce risk by reducing volatility. If a trader has 100 shares of stock, the position goes up or down $100 for every dollar change in share price of the stock. If the owner sells a 25 Delta call against those shares, the total position will now move only $75 up or down for every dollar change in stock price. Voila, a less volatile position! While a 25% reduction in position volatility may not be that much, it is a reduction. Taken with other steps to manage the overall Delta of a portfolio, every action contributes to the final result.

The obvious benefit of selling covered calls is additional income from the call premium collected. But it isn’t how much premium we collect when the trade is opened that matters, but how much we keep when the trade is closed. I’ve said that this trade can be tough to show a profit from the calls themselves, so what is a reasonable profit target from the sales of calls? Generally, if a covered call seller can hang onto 25% of the call premium collected on average over time, that’s a successful outcome. As mentioned earlier, the challenge is that most of the time, the amount kept will be more, but occasional moves up will take big losses on the call portion of the trade. These losses are offset two ways- the long stock goes up when the calls lose value, and the calls shield some of the losses of stock on down moves.

The nature of the trade is always one side is winning while the other side is losing. But there are also situations where both sides of the trade can win at the same time. Small increases in price allow the stock to go up and the short call option to decay in value with a little time passing. Looking at the original profit chart, we can see that the net profit is positive on both up moves and slight down moves, which makes the probability of profit greater than 50%. We can improve the probability by managing the trade early before the underlying price moves far from where the trade opened. This is one of several management strategies to consider.

Managing a Covered Call

As with all option trades, we have our typical choices for managing- hold, fold, or roll. But there are a lot of different scenarios that can impact our decision making, depending on price movements, implied volatility changes, and the approaching payment of dividends. There’s also philosophical strategy choices around whether a trader wants to let shares be called away, or avoid options being exercised. All these various considerations make it a somewhat complex menu of management choices for the trade that is often considered the most simple option trade of all.

Most covered call sellers I know or have read about consistently have covered call positions against their long stock. It isn’t something they sell for a while, then stop and start randomly. More than any other option trade, covered calls are a commitment to ongoing trades. The question is what that commitment is for each trader.

There are some traders that sell covered calls only when their stock is trading at high levels. The thought is that it isn’t likely to get much higher, and so it’s a good time to pull in some extra income. But what is high? And what is low? Whatever the market outlook, covered call traders need management strategies.

As mentioned earlier, most management strategies fall into the categories of hold, fold, or roll. With covered calls, holding means holding the calls until expiration or assignment, and dealing with the outcome. Folding would imply getting out when there is a win or a loss beyond a set amount, but most covered call sellers aren’t stopping when they hit a trigger, they want to keep trading. So, that leaves us with rolling, where we move from one call to another to another, collecting all the premium we can over time. I’m going to focus on holding strategies and rolling strategies as they make the most sense for covered calls.

Holding and Wheeling

When a trader sells a covered call, the default way to manage is to hold until the option expires or gets assigned. Many traders like this way of managing because of simplicity- just let the market play out. For stocks with less liquid options, frequent trading isn’t practical. Outside the most traded 100-200 most active stocks, there are few strikes to trade and lots of stocks with only monthly expirations. Many stocks don’t have any monthly expirations beyond around 45 days, so rolling month to month isn’t a legitimate choice until expiration anyway. So, if a trader is selling covered calls on a basket of stocks, many of the options can only logically be managed by holding until expiration or very close.

If a covered call is held to expiration, there are two outcomes. It expires worthless or the call is exercised and the shares sold for the strike price. The outcome determines the next step for most traders.

If the option expires worthless, most traders will turn around and sell another call option. Since options expire at the end of the week, this means selling on Monday of the following week or soon after to get as much premium decay as possible in each expiration cycle. Perhaps a trader will choose a strike and enter a limit order to try to capture a little extra premium on a small up move. If the option expired worthless because of a big down move, it could be a good time to evaluate whether to continue owning the stock or whether it makes sense to sell calls with the stock price so low.

Most covered call sellers try to avoid selling calls at strikes less than their basis price. For example, if a stock was purchased for $100 and a $110 strike is sold for $2.00, and the stock drops to $85 a share, the option will expire worthless and the trader’s cost basis becomes $98. If the trader now finds a good option to sell has a strike price of $95, this might be a no-go because there is no way to make a profit. Or it might get some premium back against the paper loss incurred. The trader has a decision to make.

I typically look for new strikes with a Delta between 20 and 30 for covered calls. I want to get good premium, and it’s okay to take on a higher probability of expiring in the money because my call is covered. Other traders sell much lower Deltas, trying to reduce assignment risk. It’s a personal choice- how much assignment risk does a trader want to get paid for.

When a covered call gets exercised and the stock is sold at the strike price, the seller has a few ways to proceed. If the stock was one that the owner was happy to be rid of, it is a good time to do something else with the capital that was freed up. But if the trader wants to get back in the position, a common tactic is to move to the next step of a Wheel strategy.

The Wheel strategy deserves its own writeup, but the covered call is part of this common covered strategy. The wheel is a cyclical strategy of selling covered calls and cash secured puts. Here is the basis steps of the Wheel:

- Sell a cash secured put out of the money.

- As long as the cash secured put expires worthless, sell another cash secured put.

- When a cash secured put is assigned into long stock, sell a covered call against the stock.

- As long as the covered call expires worthless, sell another covered call.

- When a covered call is exercised, and the stock is sold, sell a cash secured put to restart the cycle.

Many traders like the Wheel strategy as it tends to force them to buy low and sell high. Puts get assigned when stock prices go low, and calls get assigned when stock is high. For many option traders, this is “the strategy.”

Rolling Continuously

Another approach is rolling positions regularly, well before expiration. The goal is to get a nice chunk of time decay, then close the position and open a longer-dated position for a net credit. A side benefit is that assignment of the call can be mostly avoided by frequent rolling. The strikes can also be adjusted with each roll to stay close to optimal Deltas and probabilities.

Not all stocks and options are optimal for rolling. Good underlyings for rolling calls need to have good liquidity with lots of strikes, good option volume, and frequent expirations. I like stocks that have weekly expirations because they tend to have good volume and lots of choices. These stocks tend to have weekly expirations out up to six weeks, and monthly expirations every month for several months out.

As mentioned earlier, I like to sell calls with Deltas between 20 and 30. With rolls, I look for new strikes in that range where I can collect a net credit. That isn’t always possible, so we need to consider the various scenarios that can arise, and have a plan for each.

Let’s start with the easiest scenario- the stock price doesn’t change. In our earlier example, we sold a 420 strike at 42 DTE for $2 when the stock was trading at 400. Two weeks later, the premium has decayed to $1 and the stock is still at 400. We can just close our current call and sell another 42 DTE call at 420 for $2, and have a net credit of $1. We made $1 profit on a $400 stock in 2 weeks- a 0.25% return while lowering risk and the stock didn’t change. If we could do that every two weeks, we’d have an extra 6.5% return in a year. We just need the stock to cooperate with our plan. But we know that it isn’t that easy, prices change.

Rolling up when the stock goes up

When underlying stock prices go up, calls increase in cost and the Delta gets higher. The goal of each roll becomes trying to move the strike price up to get a Delta a little lower while still collecting a credit. Looking at our earlier example where a call was sold at 420 when the price was 400, let’s assume that after 2 weeks, the stock price has gone up to 410, a 2.5% increase, which would not be unusual at all. Our call has gone from a value of $2 when we sold it to $4 because it is closer to the money. If we roll back out to 42 days at a 420 strike, our new Delta would now be 40, higher than we like. If we roll to 430, we would have a 25 Delta, but we would have to pay a debit because of the premium cost difference. However, we find that we can sell a 425 strike for $4.20, 20 cents more than our current call will cost us to sell, and the Delta of the new call would be 34, closer to where we’d like to be, but not all the way. It’s a compromise. We can collect a net $0.20 credit and move our strikes up a bit. This would be my choice.

One reason I don’t get wound up about getting all the way to my target Delta is that I know that stock prices go up and down. So, while my Delta is high on this roll, if the market goes down, the Delta will come back to where I was targeting. I somewhat expect that, but I really don’t hope for that, because I get much more portfolio movement from my stock than from my call. Remember that when the price went from 400 to 410, and the call went from $2 to $4 in value, the net of that move was $8 profit- a $10 gain from the stock against a $2 loss from the call. The price move up is always a good thing when we have a covered call, even if the call’s value is a loser for us.

But what if the price keeps going up and the call keeps getting more expensive and our calls end up in the money, or even deep in the money? No matter how far the stock goes, our calls are a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic (time) value. The time value of the call is always decaying. We can always roll out to the same strike for a credit, and usually we can roll up a little as well. Let’s say our call that we started with in our example gets to a point where it is $20 in the money and has a value of $22 with 28 days left to expiration. We look around our choices to roll and find that any roll up two weeks further out will not get us as much premium as we have to pay to close, so we see that we can sell a call $19 out of the money for $22.10 with 49 DTE. Is that a good deal? I think so, because we are locking in a dollar more value if the option were to be exercised while collecting 10 cents to do it. As our calls get deeper and deeper into the money, the chance that our stock gets called away goes up, so every strike price increase we can get with a roll improves the price our stock could get sold at.

How long do we keep this up if we get deep, deep in the money? At some point, we may find that there aren’t calls that are liquid around the strikes we are trying to roll to. That’s when it’s game over for me. I’ll stop rolling and let the call get exercised and sell the stock. I’ll have a nice profit on the stock from where I started, and re-evaluate what to do. Maybe I’ll wheel back in by selling a put, or maybe I’ll look for another opportunity in another stock.

Rolling down when stocks go down

Rolling down as stock prices go down is actually a little trickier and can be a trap. The issue is that while the call makes money when the stock goes down, the stock loses several times more value. As an option trader, the challenge is to step back and see the big picture. We can’t just look at our call profit, but the total position as we strategize going forward.

A key consideration in managing rolls down is looking at the cost basis of the overall position. If our earlier example was that we started by buying stock at $400 a share, we start with a cost basis of $400 per share. If we then sell a call for $2, our total cost basis is reduced to $398. Every call we sell reduces our cost basis. Let’s be clear. This isn’t our cost basis for tax purposes, but for how we might choose to think about our overall trading position. The IRS looks at the profit and loss of each individual trade, not how trade after trade impacts your total net costs. But many traders like to think about the total capital they have spent and collected to evaluate whether to continue with a strategy.

So putting this concept to use, let’s say our stock that we’ve been discussing throughout this write-up goes down from 400 to 390 in the two weeks after we opened the trade. Our 420 call price drops from $2 to $0.25 with a Delta of 5, almost worthless. Should we roll down? We could roll to a new 410 strike 42 DTE call selling for $2. 410 is above our cost basis, so if the stock went up beyond 410, we’d still have a nice profit, so why not. We can collect a net credit of $1.75 and reduce our net cost basis to $396.25. We’ve done great on the call, but remember our stock lost $10 per share, while we only made $1.75 on the call.

If the stock bounces back from here, we would tackle the position with a roll up strategy like we just discussed. But if the stock keeps going down, we can keep rolling down.

Let’s say that after our roll down, the stock drops to 375 after another two weeks and our call drops to 10 cents of premium. We look at 42 DTE strikes and find that we can sell a 395 strike for 2.10 because IV has increased from the drop in stock price. Is this still a good deal? If we sell this call, our net cost basis will now drop to 394.25 while our strike is 395. If the option were to be exercised at 395, we’d have a small profit, so if we still like the stock, this trade could still make money.

If we take another hit to the stock price, any rolls of similar price differences at the times we have been trading will need to be sold below our cost basis. If we want to keep our strikes above the cost basis, we can go further out in time, or take a lot less premium at lower and lower Delta values.

If we follow the stock further down with even lower strikes we enter into a lose/lose situation. If the stock keeps going down we lose, and if the stock goes up beyond our strikes we also lose because we are likely to have to sell for less than our net cost basis.

By this point most traders will either abandon selling calls on the stock, or dump the stock and find something else to trade. Every trade needs a plan, and one part of the plan is knowing what you will do in a big loss- is there a price that enough is enough? As we’ve discussed at other points, the biggest mistake most traders make is taking small profits on winners, and holding onto big losers- a recipe for a losing portfolio over time.

Big moves up and down can be tricky to manage for covered call holders, even stressful. But considering that compared to holding stock alone, a covered call seller is still in a less volatile place.

Avoiding Assignment

Is there a way to know if a call that we sold is going to get exercised by the buyer? Most of the time it’s pretty clear cut, but occasionally it is luck of the draw. Put yourself in the shoes of the call buyer-when would it be a no brainer to exercise your call option? In the money at expiration is generally automatic, but early exercise is usually driven by either an event in the next day that makes a buyer want to lock in a profit, or a need to close out a call that has become illiquid. Let’s go through these scenarios and see how to avoid being on the other side of the trade.

This section assumes that a trader wants to avoid assignment. As explained earlier, there are lots of traders and individual situations where a trader is satisified or even desires to have their stock called away. If you want to have your short calls exercised, do the opposite of this section’s advice and keep your calls in values that are subject to assignment.

A quick overview of the mechanics of assignment. Options are managed by an options clearinghouse. Option buyers have the “option” to exercise their option contract at any time prior to expiration. The buyer notifies their broker that they want to exercise an option and the broker notifies the clearinghouse. The clearinghouse then randomly matches up the requests to exercise options with short option contracts that are currently open. The clearinghouse assigns these contracts to sell their shares to the option buyers who have exercised their option. Option owners typically have until 5:30 PM Eastern Time, or an hour and a half after the market closes to notify the broker they want to exercise their call. The actual transaction generally is done around midnight while the market is closed. Key points are that it is up to the buyer, happens when the markets are closed, and is random.

Expiration Assignment

If a call is in the money when it expires, it almost certainly will be exercised by the buyer. Most brokerages automatically exercise all their customers options that expire in the money as a courtesy and also to save the administrative hassle of having every option buyer request the option to be exercised.

The logic is simple. The stock is worth more than the strike price, so it wouldn’t make sense to not exercise the option and buy the stock for less than the current price. That was the point of the buyer in purchasing the call option to begin with, to make money when the stock went above the strike price.

Occasionally, an option might expire right at the strike price or a penny or two in the money. Some option buyers may choose not to exercise because of the costs outweighing the benefit of buying the stock at a lower price. Or some news may make it clear that the stock will be worth less when the market opens the next day, make exercising a losing proposition. However, these scenarios are very rare, and a trader shouldn’t expect or count on them.

Just because a stock expires out of the money doesn’t mean that it won’t be exercised. When there is positive news after the close, and option buyers anticipate that the stock will open above the strike price, they can still exercise the option after the market close but before the clearinghouse assigns options to be exercised. If a call option buyer has a call with a strike price of 420 and they expect the stock to open at 421 the next day, they can exercise the option buying at 420 and sell the next day for 421. If you are on the other side, you shouldn’t be surprised, it happens.

How do we avoid all these expiration assignments? Simple, don’t hold options to expiration. Close or roll out options before they expire. Even if your plan is to hold to expiration and then sell another, you can close the expiring option on expiration day and sell a later expiring one at the same time, so you can keep getting decay over the weekend, since expirations generally happen at the end of the week.

Even if a call is in the money, you can roll it out in time and not get your stock called away at expiration. There is still early assignment risk and we have ways to greatly reduce early assignment, but expiration assignment is generally automatic.

Early assignment due to dividends

Probably the most common reason for call buyers exercising an option early is dividends. On the day that a stock goes ex-dividend (when owners of stock are credited with an upcoming dividend payment) there is a big benefit to being a stock owner vs a call owner. The upcoming dividend payment is baked into the stock price prior to the ex-dividend date and comes out after it. Call values also reflect this in pricing.

If a call owner has a call with a strike price in the money or within the amount of the anticipated dividend and less than the extrinsic (time) value of the option, they will execute the option every time. In fact there are traders that will buy options at the close of the day before a stock goes ex-dividend to immediately exercise for a profit if the arbitrage opportunity exists. It usually doesn’t because the market is very efficient.

There are two ways to avoid assignment on ex-dividend day. Have a call further out of the money than the dividend amount, or a call with more extrinsic value than the dividend. Let’s look at each situation.

If you have a covered call that has a strike price close to the current stock price, you are likely to be assigned. If however, the call is well out of the money, it won’t be exercised.

For example, if a stock is trading at $400 a share and you have sold a $420 strike call with a $3 dividend being credited the next day, no call buyer will exercise because they would have to pay $420 to own a $400 stock with a $3 dividend, a value of $403. Why spend $420 when the stock can be purchased for $400?

On the other hand, if the stock price is $400 and a call buyer owns a $401 strike call when a $3 dividend is being credited, then the option can be exercised to buy a stock for $401 that has a value of $403. Good deal for the buyer, right? Maybe- it depends. It depends on the extrinsic value of the call option. And you thought covered calls were a simple topic?

The extrinsic (time) value of a call impacts whether it makes sense to exercise or not for a dividend. For example, if a stock goes ex-dividend tomorrow trading at $400 today with a $3 dividend, would it make sense to buy a $401 strike call for $4 and exercise it? The buyer would pay a total of $405 to get a $403 value, a loss. On the other hand, if there were a $401 strike selling for $1, buyers would line up for blocks to buy as many as possible to pay $402 for a $403 value. In practice, prices wouldn’t work that way, because stock prices are varying while the market is open and option prices are adapting to make capturing a dividend on a stock close to a break-even trade as ex-dividend day approaches. So, you won’t find an option priced lower than the combination of stock price and upcoming dividend, but you can find options more expensive than the combination. What determines whether it is the same or more? Time value.

Extrinsic or time value of an option can make a call option more valuable to hold than to exercise to capture a dividend, even in the money. In our previous example we discussed a $401 strike call with a value of $4 vs. $1. What determines the difference in prices? Time and to a degree implied volatility. We can’t do anything about implied volatility- it is whatever it is. But we have total control over the time value of our covered call option.

The further out our covered call is from expiration, the more time value it has. So, if we have a call with a low amount of time value, lower than the coming dividend, we can roll the call out in time to make it have more time value than the dividend. The greater the difference in time value vs the upcoming dividend, the less likely the call will be exercised.

If we have a covered call with a strike price near or in the money, we can avoid assignment by rolling to a point in time where the extrinsic/time value is more than the expected dividend. It doesn’t guarantee that a rogue call owner won’t exercise for a loss, but it becomes highly unlikely.

As an example, if we have sold a 390 covered call trading for $11, expiring in two weeks, and the current stock price is 400, and a $3 dividend is expected to be credited to owners of record the next day, we are in position to have our stock called away. Why? Because our combination of strike price and call value is $401 (390 + 11) and the value of stock plus the dividend is $403 (400 + 3). Any owner of a call would cash in their call option for stock and collect the dividend. However, if we roll out 6-8 week further in time and keep our 390 strike but have a call worth $15, we are likely safe to keep our stock. Our $15 call has a $10 intrinsic value (400-390) and a $5 extrinsic value (15 -10). The extrinsic value is more than the $3 dividend. Seen another way, the call strike price and value now total $405, $2 more than the value of stock plus dividend, so it’s not a good value to exercise the call. Generally, if we have a covered call within a few weeks of expiration at or in the money, it will be exercised on the night before an ex-dividend date. Calls significantly further out in time will be safe.

For calls deep in the money, it can get difficult to go far enough out in time to have enough extrinsic value to be greater than the coming dividend. I once had a covered call stock run away from me to the upside, and I rolled my calls over and over. Eventually, my strikes were 25% below the stock price. Even with calls 6 months out in time, I had very little extrinsic value, almost all the call’s value was intrinsic. The Delta of my call was almost 100, so I had capital tied up that wasn’t going up or down hardly at all, no matter what the stock did because my call’s price moved almost exactly opposite of my stock. I decided as a dividend approached that it was time to let my position get called away, because I didn’t want to roll out 6 months further to get more premium. Sometimes, we just run out of ways to keep the position alive.

What timeframe for Covered Calls?

Throughout this write-up I’ve used 42 DTE as an example for writing covered calls. Is this optimal, or is there better durations? Generally, I like starting around 6 weeks and not letting my positions get within 3 weeks of expiration. I can adjust every few weeks or so, and I don’t have to watch my positions constantly. There’s good decay, at least enough for me.

Trading closer to expiration means faster decay, but more volatility in prices. For traders that can manage the additional changes in price, this might be fine. This is a covered call, so the worst case scenarios aren’t that bad, especially if the plan is to hold to expiration, or if the plan is to “wheel” the position.

Trading farther out in time allows for even lower volatility in exchange for less premium decay on a daily basis. Selling covered calls with more time to expiration can allow a seller to sell strikes farther out of the money as well for the same Delta value, giving the position more cushion in an up move. More time is generally equal to less stress.

The right strike for selling Covered Calls?

In addition to choosing a timeframe for selling covered calls, a trader has to pick a strike to sell. I tend to choose strikes with Deltas between 20 and 30 for covered calls, which is inside the expected move. Because I plan to roll well before expiration, I will likely roll before the stock will end up in the money. The calls are covered by stock, so I’m not particularly worried about my calls getting into the money on occasion.

Other traders are more conservative in choosing call strikes and want to be well outside the expected move. They will give up much of the premium to keep the probability of their call from getting in the money. There’s a somewhat popular book on selling covered calls that recommends 12 as the right Delta for selling a call. The author never says it, but 12 Delta is more than a one standard deviation move at expiration, and so it is “likely” that the call will expire worthless. If that’s the goal, then that’s as good of logic as it gets.

On the other side, if a trader wants out of a position, the value can be maximized by selling a call at the money and having a high probability of having the position called away. A “wheeling” trader might want a high delta especially when prices appear to be peaking, to sell the stock before it starts going down. The higher the Delta, the more the call counters the stock, reducing the position volatility. It’s depends on the trader’s goal for the trade.

Final Thoughts

Trading options is all about making choices of trading one position for another, trying to move to a position that has better probabilities of profit, or less risk, or some other variable that is important to the trader. We can see there are lots of ways to trade what many would consider to be the most straight-forward option trade of all, the covered call.