Sometimes you stumble across something that just works. In option trading that is actually rare. The 21 day broken wing put butterfly sounds like a something a entomologist chef might come up with, but it is actually a trading strategy that works really well and is very repeatable. What if I told you that I have a strategy that often makes a 10% return in two weeks with a good probability of success, so good that I once had 26 winning trades in a row. Oh, and if things work out right the return could be much higher, although not likely.

I first learned about broken wing butterfly trades from TastyTrade. In fact, it is the favorite trade of two of their mid-day hosts, Nick Batista and Mike Butler. They use broken wing butterflies in a different way, which I found frustrating, and after experimenting, I came up with this very specific variation.

When I first explain this strategy to people they look at me like I’ve gone looney, and I get it- this is not a simple concept. So, let’s start by explaining what a butterfly is and what makes a broken wing. Then we’ll dig deeper from there.

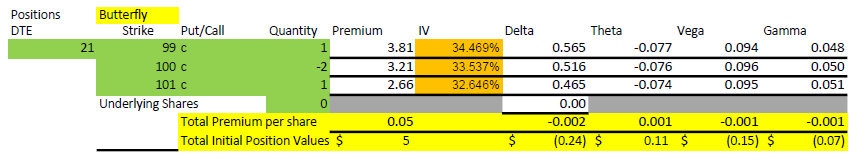

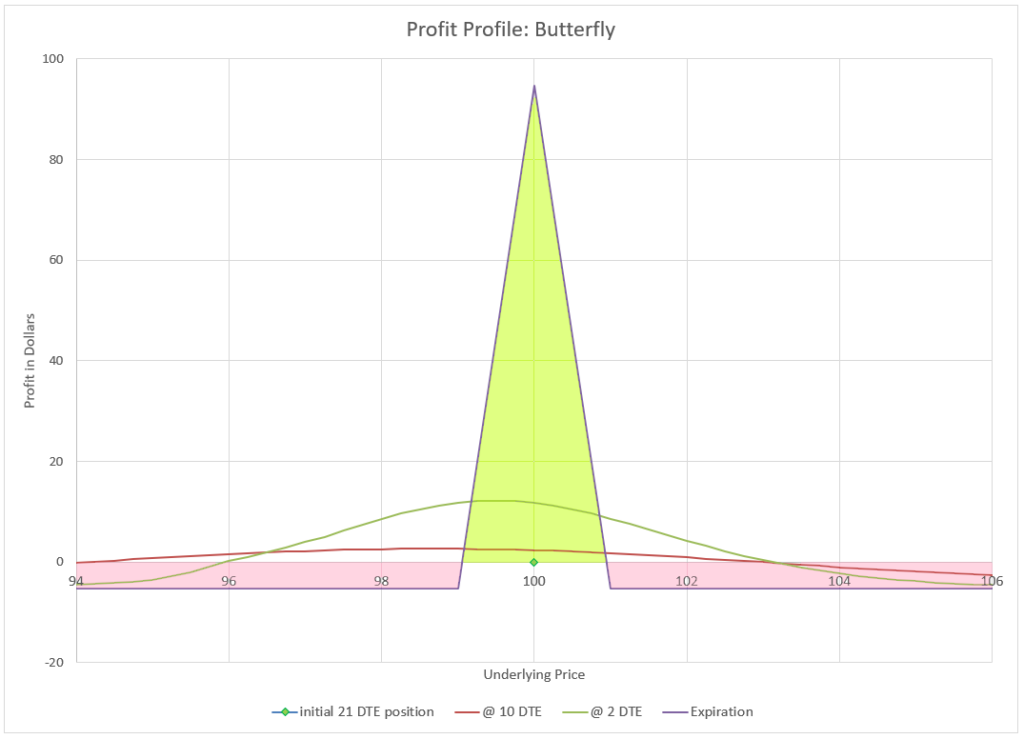

The Regular Butterfly

A butterfly is a three part option position that is made up of four contracts, two that are sold, and two that are bought. A true standard butterfly has two of the same contracts spaced equally between one contract above in strike price and one below. For example, we could sell two contracts at a strike price of 100, and buy a strike at 99 and one at 101. The 100 strikes would be the body of the butterfly, and the 99 and 101 would be the wings. This could be done with either puts or calls, it works either way. You may wonder why would anyone think this is a good trade? Well, since you buy two options and sell two options and the average strike price is exactly the same, the premium to buy this strategy is usually fairly small, maybe 2-5% of the width of the wings, or 2-5% of $1 wings in our example. So, for 5 cents you can own this position. It might be more or less depending on how many days until expiration, the current price of the underlying and the implied volatility, but generally the cost is small if there is some time until expiration. Now, if the underlying happens to close right at $100 on expiration day, it will be worth $1, a huge gain on 5 cents. However, the chance of that happening is slim. If the underlying closes between 99 and 101, the result will be positive, between 0 and $1.00, depending on how close to $100 the close is. See the profit at expiration chart. Most likely, the underlying ends outside of 99 and 101, and the premium spent is lost. It is kind of like putting a bet on a single number on the roulette wheel. It’s great if you win, but mostly a losing strategy.

One issue is that the profit from this trade doesn’t occur until right at expiration- until then the premiums tend to cancel each other out, and it is hard to get any profit early. A similar put/call combination trade is the iron butterfly, with credit put spread and a credit call spread with the same short strike. I learned early that these trades take forever to decay in value and are only good when you hit the short price right at expiration. So, I don’t like butterflies or iron butterflies, mainly because I don’t like expiration day drama and it is a low probability trade.

Introducing… the Broken Wing Butterfly!

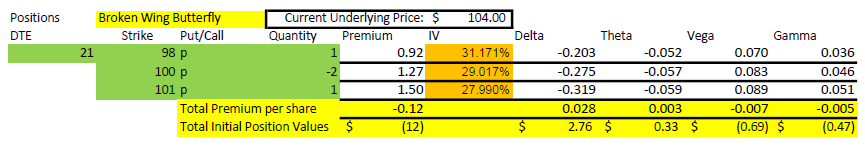

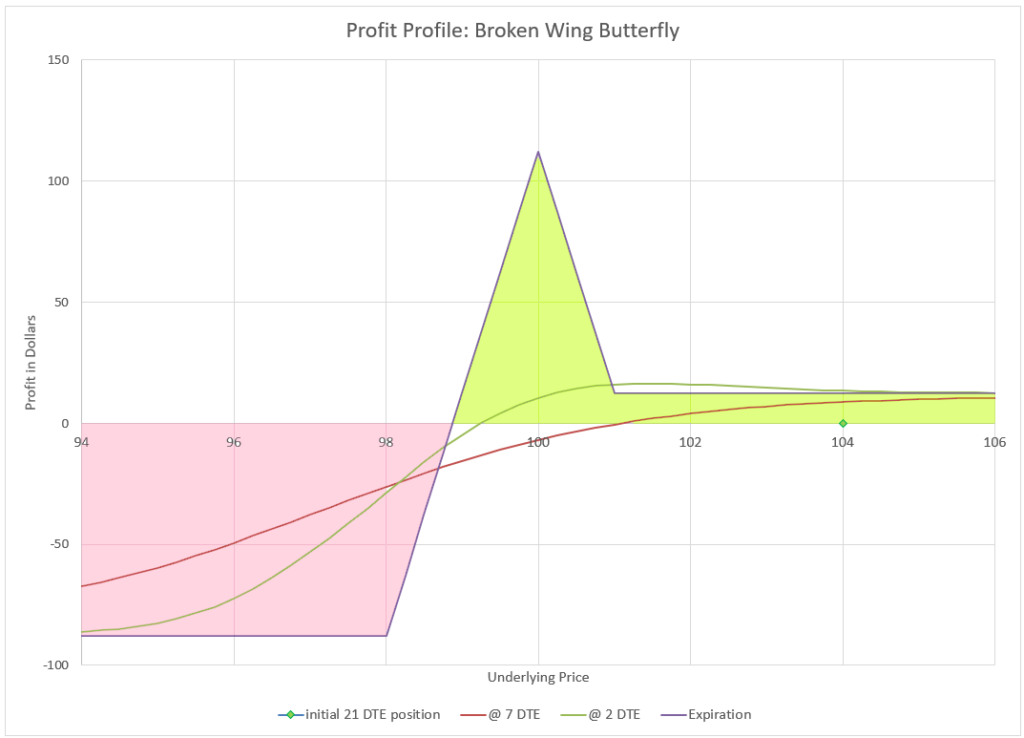

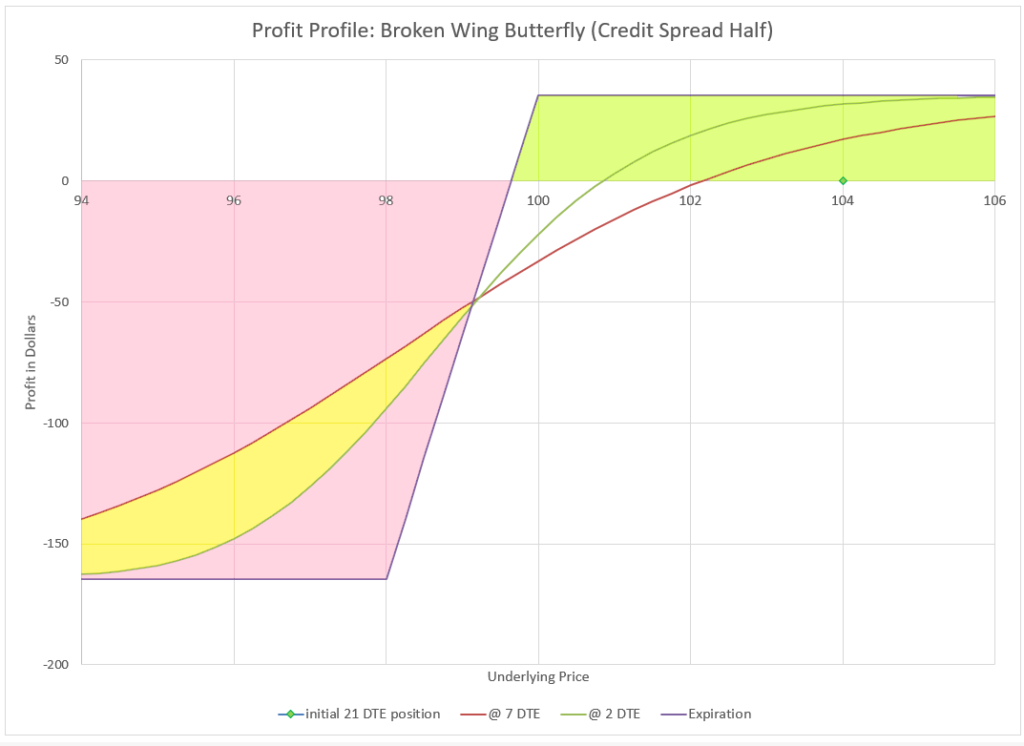

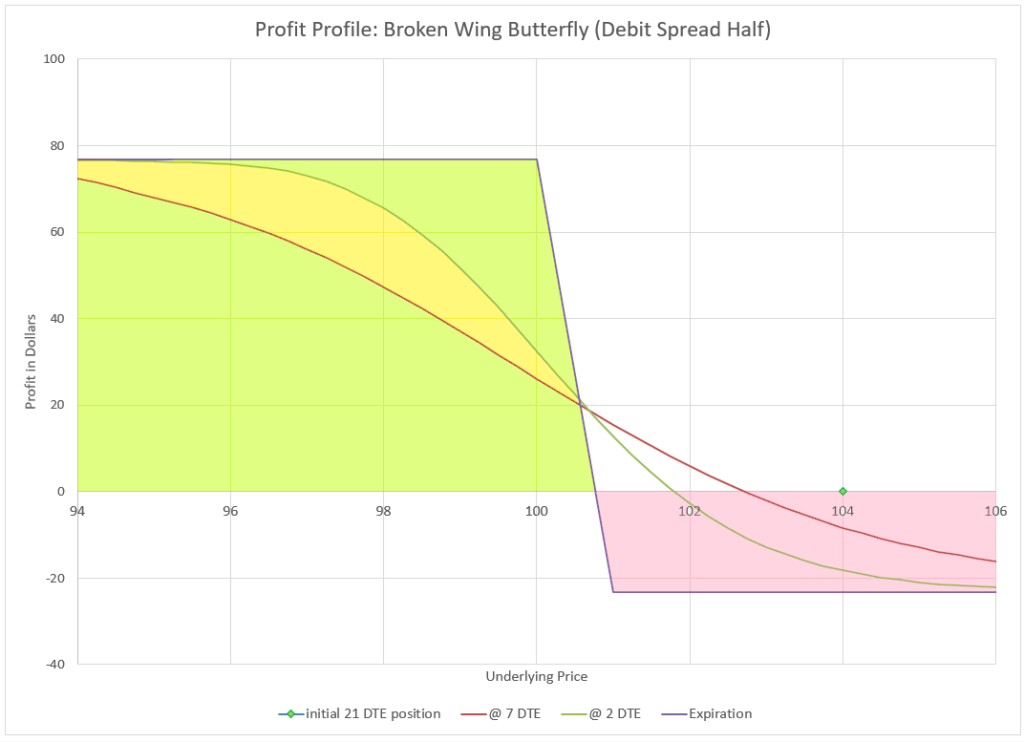

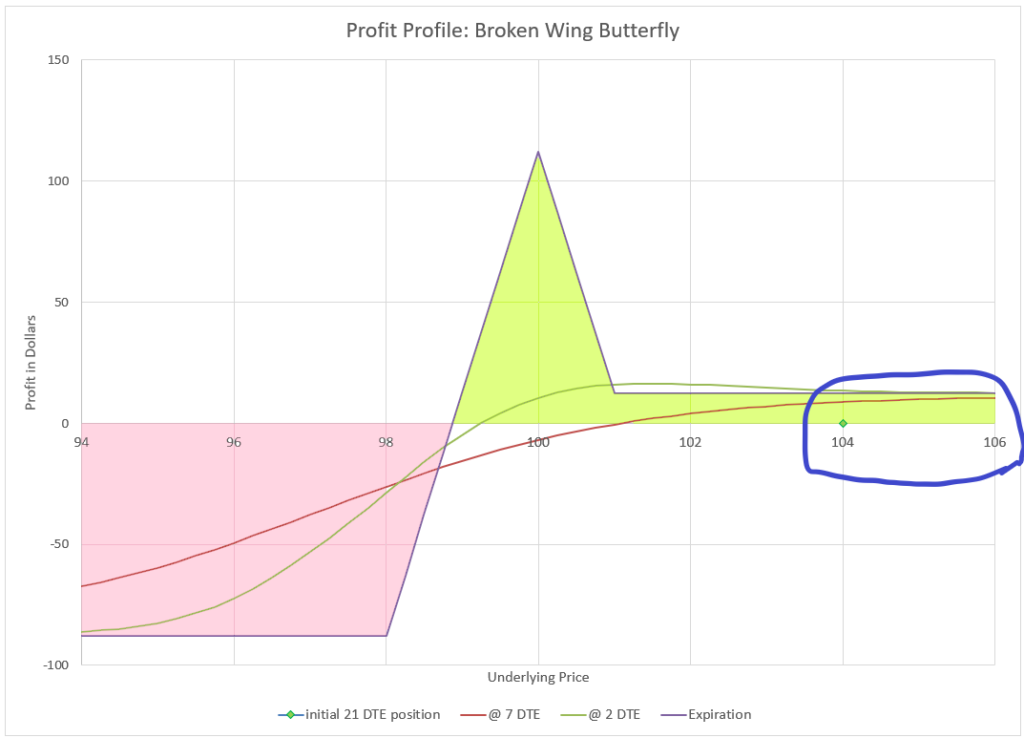

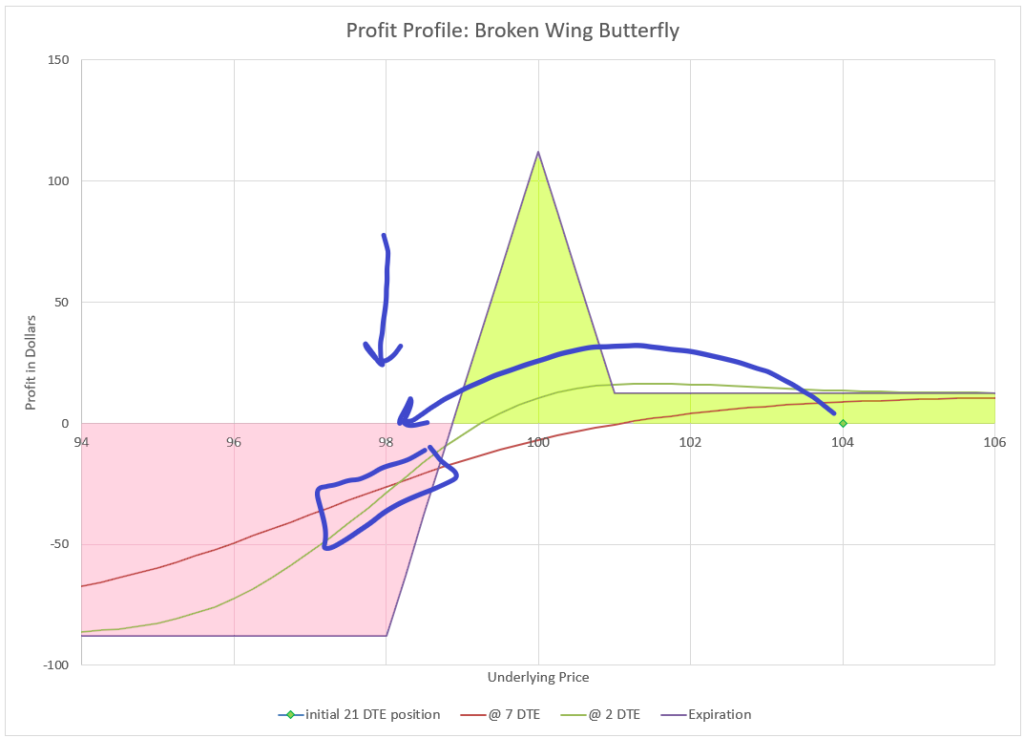

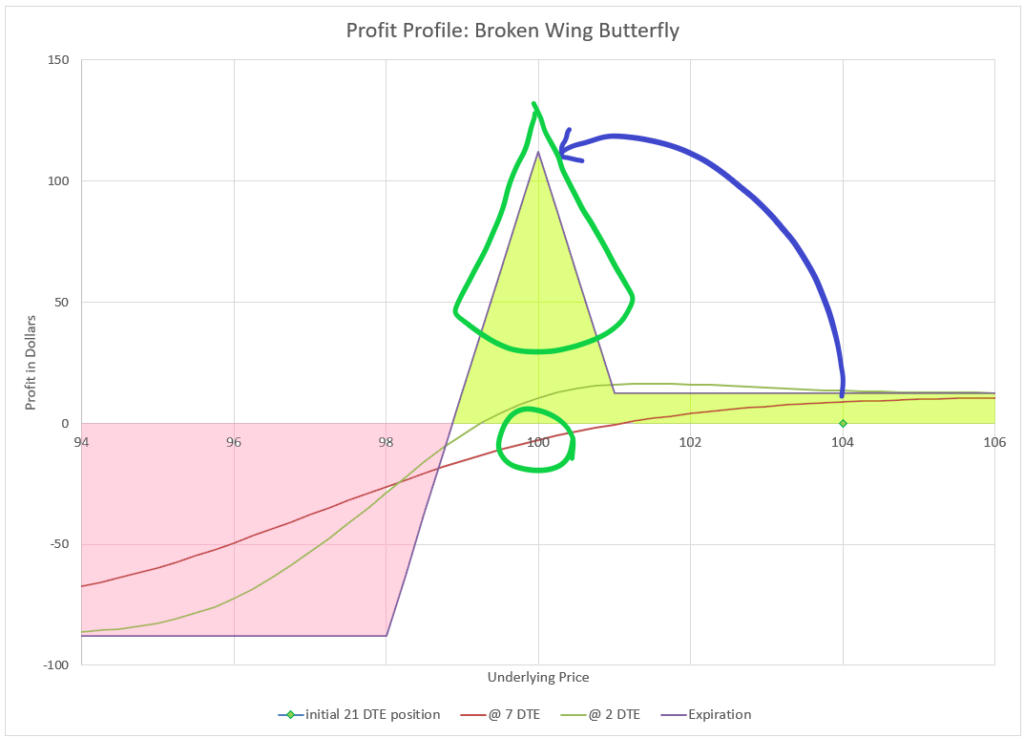

But, what if there was a way to collect a premium and take away one side of the risk completely and still have the possibility of a big return? Enter the broken wing butterfly. The way I trade this and TastyTrade recommends as well, is that instead of equal width wings, we buy the cheaper wing twice as far away from the body as the expensive wing. So, if our 99/100/101 example was a put butterfly, we’d instead buy a 98/100/101 broken wing put butterfly. We would sell two 100 strike puts and buy one 98 put and buy one 101 put. This change will move our transaction to a credit, a credit we can keep if the underlying expires above 99. And if we expire at 100, we can collect $1, regardless of what we collected when we entered the trade. The catch is that if the price expires below 98, we owe $1.

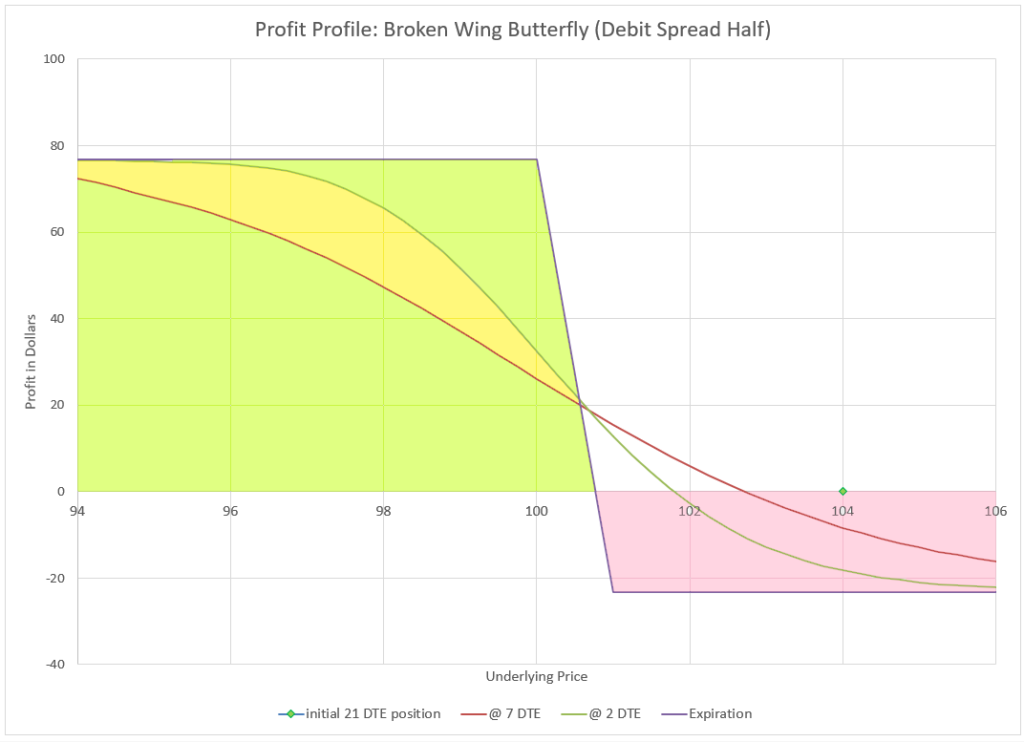

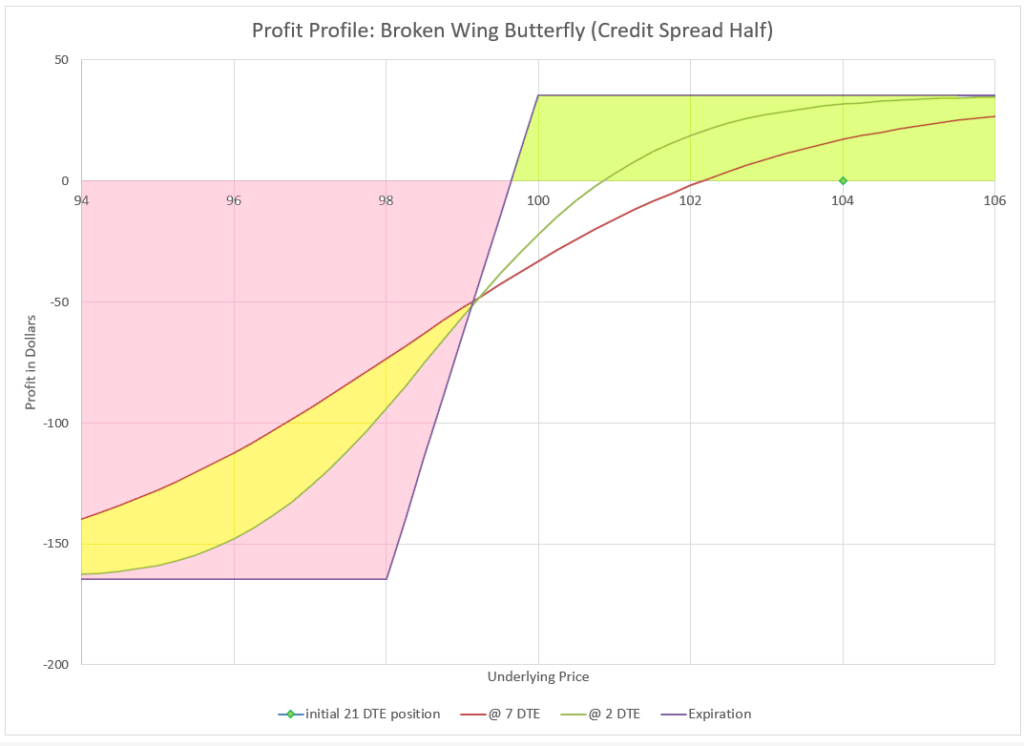

One way to think of a butterfly is to think of it as credit spread and a debit spread. Outside the wings, the two spreads cancel each other out at expiration if the wings are equal, and the smaller once cancels out half the larger one if the credit spread is twice as wide as the debit. If the spread ends out of the money, both spreads are worthless. The sweet spot is right at the body of the butterfly.

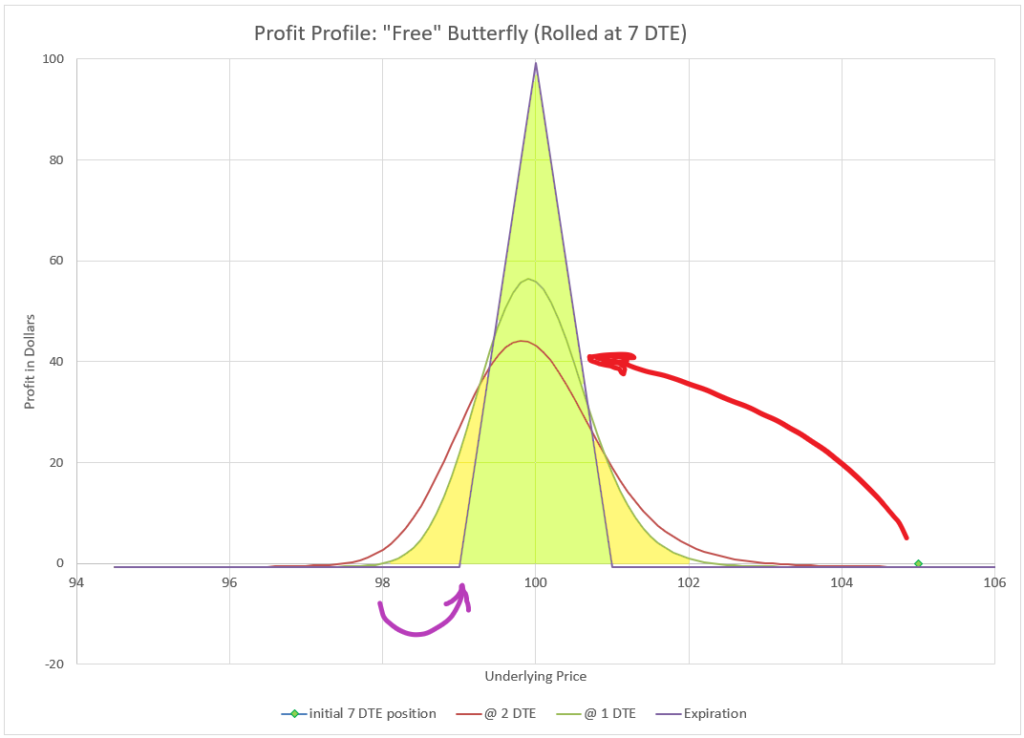

The folks on TastyTrade like to collect a premium on a broken wing butterfly and then look for an opportunity to roll the broken wing to a normal wing strike price for less than the premium they collected. With this, they then have a “free” butterfly that can not lose and could still make the max at expiration while consuming no capital. It’s a great idea, and it works, but I found it challenging to manage. To be able to roll for less than the credit received, the underlying has to move away from the wings quite a bit, making it unlikely that the strike will end up on the body at expiration. They equate it to getting a free lottery ticket. I often try to keep my premium and get out as quick as I can. And I’ve found a formula that works for me.

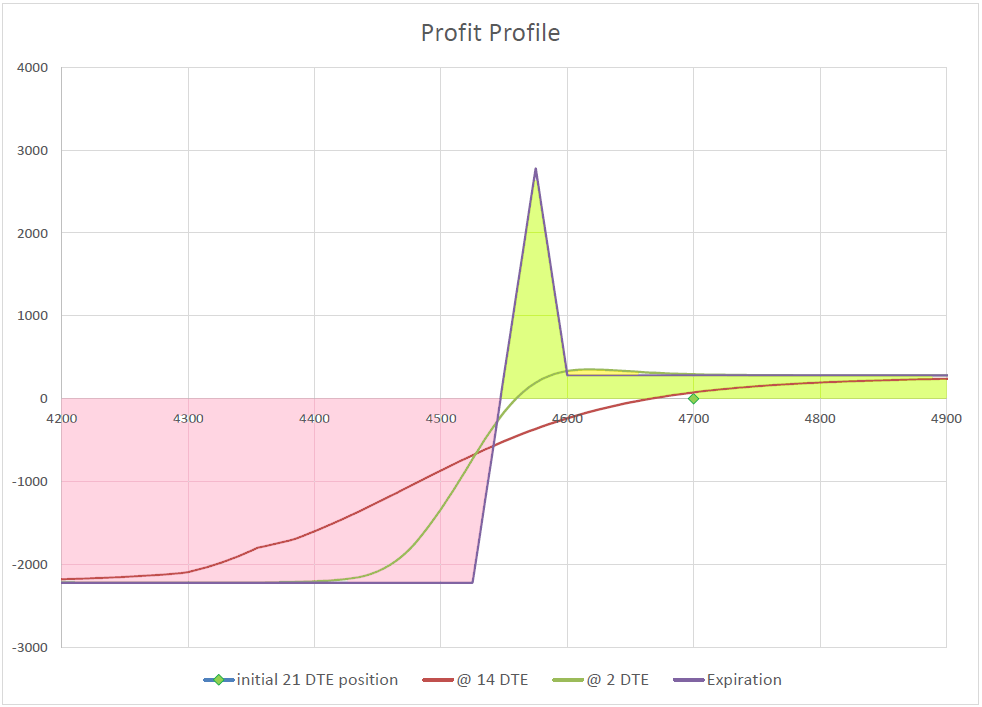

You may be able to guess from the title that the broken wing butterflies I trade are puts and I like them to have 21 days to expiration (DTE) when I enter. I also almost always trade the same Delta values at entry, 32/28/20. I also stick to index options or options on index funds. I will only enter a trade if I can collect 10% or more of the width of the narrow wing, but at this timeframe and delta, that is almost always the case. I then buy back the trade when it gets to a value of around 1.5-2% of the width of the narrow wing. Usually, this happens with around 7 DTE, if the market is flat or rising, and I have a 10% return on capital in two weeks.

This works a high percentage of the time, but not always. When the market goes down, I manage the position and hope for the price to land right at the strike price of the body, where I can make 100% on top of what I already collected. When the market really drops, I maneuver with a series of moves to try and get my money back, or I could owe up to 100% of the capital at risk. I’ll detail how I manage these drama scenarios in a bit, but first let’s break down why I chose each element of the trade to start with.

Why puts?

I mentioned at the top that butterflies could be created with puts or calls. I’ve tried this strategy with calls, and my success rate is much lower, with much more drama. I specifically use out of the money puts, because they are much more likely to expire worthless than out of the money calls. The market has a tendency to drift in a positive direction most of the time, and the times it goes negative are generally are infrequent and unpredictable. Additionally, the Delta values I use are specifically chosen for this combination of time to expiration, combined with puts and the use of equity indexes. Implied volatility skew changes these pricing and Theta decay relationships between puts and calls, so a broken-wing butterfly with calls is just different than with puts.

One over-arching option trading principle that I used to follow is to combine put risk with call risk. So, is there a similar strategy for calls that could take double advantage of the capital at risk, using the same spread width and timing? Maybe, but I haven’t found one that delivers a high probability of profit and lack of drama. I’m looking for one, modeling possibilities, and testing, but so far I am without repeatable success. When I find it, that strategy will be added as a combination. Until then, I happily trade this strategy, collecting a 10% return on capital in about two weeks.

The only call strategy that I’ve had success with is to sell a spread in the 11/6 Delta range with the same capital risk as the butterfly. I can collect another 5-10% on the same capital. However, some brokers mistakenly add this to buying power by pairing it with the twice as wide credit spread in the butterfly to make it an unbalanced Iron Condor. That defeats the purpose of double using capital for puts and calls.

Why 32/28/21?

When I tell people that I use strikes at 32 delta as the starting point, many think this is taking on a lot of unneeded risk. I get that, because under virtually any other circumstance, I avoid selling puts with deltas over 20. But by trial and error mostly, I’ve found that this level of delta provides rapid decay in this timeframe, and tends to be safe from testing the vast majority of the time.

When I first started trying this trade, I looked to just collect a positive premium, with hopes of collecting the 100% lottery payoff. Over time, I realized that the real win was keeping the premium collected up front, so I looked to maximize the premium without taking on a lot of risk. Initially, my goal was to find a combination that collected at least 10% of the width of the narrow spread. I’d click different strike combinations until I found something.

Eventually, I locked in on 32/28/21 delta. I don’t always do these deltas, because each time I trade, I have to use whatever is available at the time. So, I usually start by looking for a 32 delta strike if there is one. If not, I’ll take the next closest- the next lower delta if I have to pick between two different ones. Then I look for the 28 delta strike. I try to keep the width between these no more that 4 delta, so if I have to pick, I’ll take a width of three over five. The final strike is simply twice the distance away from the mid-strike as the upper strike. It usually works out to be around 21, but depending on how close the first two strikes are to 32 and 28, the lower strike delta can vary a bit.

I’ve found that at 21 days, these strikes consistently have a premium of well over 10% of the width of the upper spread. I get a bit more when Implied Volatility is higher, as it has been in 2020 and 2021 after Covid hit. If I pick slightly narrower width strikes, I collect more premium as a percentage than slightly wider strikes, although wider strikes collect more actual premium per contract- it just takes more buying power. So, I pick strikes generally around 32/28/21, which exactly is a choice at that point in time, trying to get the best value.

Keep in mind that the short strikes are the 28 delta strikes, and break-even is between the 28 and 21 delta strikes. So, if you use delta as a probability indicator, there is a 75% chance of the butterfly making money at expiration. However, my experience is that the trade has done much better than that probability.

Why 21 days?

Butterfly trades are notoriously slow to collapse in value. When I first started trading the broken wing butterfly, I traded much longer expirations, like 42-45 days, but I noticed that the value of the overall position didn’t really decay much. All the decay of the different parts cancelled each other out. However, when I held on after 21 days, the value started quickly collapsing. This is true as long as the price doesn’t drop much from when the position is opened- odds are over half the time. It seems that for these strikes, these are the magic timeframe.

I’ve looked at trying to explain this by analyzing the theta and delta of the combination, but theta decay doesn’t really explain the way the position drops, nor does delta. Delta is slightly positive, and as price moves away from the strikes, the position benefits.

Why a butterfly vs a simple spread?

After I started doing this specific trade for a while, I started thinking that it was kind of silly to have the complexity of a butterfly when I could collect the same premium percentage on a simple credit put spread at a lower delta. A put spread with deltas of around 20 and 17 will net about the same premium at 21 days as the 32/28/21 broken wing butterfly. The spread is simpler, lower delta, so I expected it would work as well or better.

However, when I did a series of trades with the exact same premium at the same width of spread, a funny thing happened. The butterflies decayed faster. After doing this several times, I decided it wasn’t a fluke. The unique relationship of the different legs causes the value to evaporate faster for winning trades. So, I went back to trading broken wing butterflies exclusively in this timeframe.

Why target 2% at 7 days?

I target buying back at 2% with 7 days left for a couple of reasons. First, it seems to work almost like clockwork. I put in a good until cancelled order to close for 2% of the width as soon as I open the position. Then, most of the time, I find the order executes with either 7 or 8 days remaining. At that point, there isn’t much premium left to decay, and the buying power is best used on another position. In our example trade, I started with 12% premium compared to risk, so if I close at 2%, I would keep 10%, which is pretty awesome return for being in a trade for just two weeks.

I could get out earlier at a lower profit, but I see the decay really keep going in days 7-10, so it makes sense to get the most reasonable possible once decay starts. It tends to work out to about 5% each week, and with only 2% left for the last week, it makes sense to start a new position to get 5% the next week instead of 2%.

Why options on indexes vs stock options?

Stocks tend to have more tail risk, or make big moves beyond what is expected compared to indexes. While indexes can move down large amounts, they do it less often than individual stocks. Indexes don’t have earnings risk, and news impacts indexes less than a story about an individual company.

Many people like to trade options on individual stocks because they often have higher volatility and more premium per option. However, in spreads this advantage is much less, as both the short and long strike have increased premium, greatly cancelling the benefit. In the end there isn’t much additional premium, but a lot of increased risk of outsized moves. So, for this strategy, boring moving indexes are best.

What if the position is tested?

So far, I’ve talked up all the benefits of the trade and the positive outcomes. The trade wins the vast majority of the time from my experience, but not always. So, what is the plan when the index goes down and tests or breaks through the breakeven point?

Close for loss?

The quick answer is to simply close the spread and take a loss. The butterfly structure helps keep the loss reasonable as the price moves through the strikes. Until the last few days before expiration, you can get out without a lot of damage. For example, when the price goes below the mid-strike with more than 3 days left, the premium is about 30% of the width. Closing would be losing likely 15% (30% minus the 15% you collected initially). Or, if you wait for the lower strike to be breached, the premium will be around 40% of the width until the final few days. The loss would still be under twice the premium collected in most cases. Just set a stop loss at a point where you are okay getting out.

But, do you really want to close? The probability of touching the break-even point of half-way between the mid and lower strike is about 50% before expiration, based on that point having an initial delta of 25. And 50% of those touches will end up profitable. If you put on a stop loss, you may often find yourself stopped out right before the position turns around and profits. Still, when you are starting out, I’d suggest getting out if the lower strike is breached, saving well over half your capital for another day.

Roll the losing side?

Alternatively, you can split the butterfly into two spreads and manage them separately. The upper spread is a debit spread, and when tested, it will have a positive value. The lower, wider spread is a credit spread that loses money when tested. The upper debit spread will be more in the money and hedge the wider spread for much of the price decline. A potential action is to sell the debit spread collecting a big premium and roll the wider credit spread to a later expiration, and wait for the market to turn around and reward you. The debit spread will have over 50% of its width as premium when the mid strike is breached, and the credit spread could be rolled to a later date for a credit if the price hasn’t dropped too far, but if a debit roll is required, the part of the proceeds of the sale of the debit spread can be used to pay the debit required for the roll.

Once the credit spread is rolled, it can be paired with a call spread and create an iron condor, or be used in a number of ways. The big watch out is that since the credit spread is twice as wide, it requires twice the buying power to maintain going forward. If the price recovers, the credit spread can be bought back for less than the debit spread was sold for.

Why/how does the buying power requirement double? It may not be obvious, but in our example, initially the max loss is $100. The debit side is $1.00 wide and the credit side is $2.00 wide. If the market drops below the strikes at expiration, the debit side will be positive $100 in value, the credit side will be a negative $200, and the net will be the difference, which is negative $100. So, let’s say I sell the debit spread for $60, and roll the credit spread out for a $30 debit, my cost basis would go from $12 credit to $42 credit, while my capital at risk would go from $100 to $200, because I now only have a credit spread. In addition, the new position will require a big move up to get to our new breakeven premium value of $42. There’s a lot of moving parts in this close and roll, and it takes some study to see what has happened.

Or hold for a shot at the big win?

Finally, there is a third option, turning a potential loss into a big win. At expiration, if the price lands at the mid strike the debit spread is maximum profit at 100% of its width, and the credit spread is worthless. So, a trader could collect 10-15% of the width when opening the trade and then collect another 100% of the width at expiration. Unfortunately, the odds of this happening are really small. But, there is a decent possibility of the butterfly having a positive balance on expiration day- if the underlying index price is close to the short mid-strikes. So, it is possible to close a tested butterfly for a credit on expiration day, maybe even a day before. You could actually collect a credit to open and a credit to close!

So, what to do? It all depends on time and how convinced a trader is that the market will bounce back. Was there some big event that temporarily scared the market, or is the market trending down with no end in sight? I try not to predict where the market is headed, because generally I don’t know. But some people use technical analysis to help them decide how strong moves are and the likelihood of a reversal. If a reversal is coming and there is time, then it makes sense to let the position ride. Three weeks is actually a long time if the market moves against a position, so a snap decision isn’t critical, but an overall strategy is.

My plan is that if the market moves strongly down and through all my strikes, I close the position and move on. If it slowly drifts down, and goes through the mid-point while there is more than 7 days, I look to sell the debit side and collect as much as I can, and then roll out at least a week on the credit side and either collect additional premium or roll down a strike if possible.

If I reach 7 days and the price is sitting near the upper strike, I keep the trade on until either the price moves up far enough that I have a profit, or it drops below the bottom strike and I close. Otherwise, I hold on and wait to see if I can collect premium when the butterfly switches to positive premium. This means there are a few tense days waiting in an in between zone. At 2-3 days left, the lowest strike starts to have very little premium if the price is at or above the mid-strikes, and the butterfly can show a small positive value when price hits the mid-strikes. As expiration approaches, the amount of potential positive value increases. In these situations, I put in an order to collect a credit, perhaps 10% of the width of the upper spread with 3 days to go, and bump it up to 20% for the last two days. If I still have the position by mid-day of expiration day, I look for a reasonable exit position. While I could hold all the way to expiration, I’d rather control what I collect and avoid a late day move that turns a reasonable profit into a large loss.

Fortunately or unfortunately depending on your perspective, I’ve only been in a position on expiration day a few times. My goal with this trade is low drama and low maintenance, and not to try to hit the elusive 100% profit strike. The last time I had a position on expiration day, I closed by collecting an additional 10%, so I made around 22% in three weeks. On that day the price movement didn’t look like it was headed for the point of maximum profit, so I closed when the credit opportunity was available.

The most I’ve made on one of these trades is when I closed the narrow side for a 70% credit, and bought back the wide side several days later after rolling for 30% of the narrow width, meaning a net closing credit of 40%, in addition to the 12% initial credit I collected to open the position. When things go wrong, there is actually the most potential for the most profit.

The thing that gives me confidence when the position gets tested is that the market has a positive bias. Over time the most likely direction for the market is to go up. If I stay patient, more often than not, the market will reward my patience. It also helps that this is a defined risk trade- I know my maximum loss when I start, so in many situations I’m willing to hold on waiting for a turn-around. If I end up with an in the money credit spread, I can collect money from an equal width call spread to finance rolls until I get out.

The “free” butterfly

There is one more unique choice for managing a winning broken wing butterfly. Instead of buying back the whole butterfly when the profit has been made before expiration, the bottom strike could be moved up to an equal distance away from the mid strike for a small debit. So, in our example, we would move the short 98 strike up to 99. The result is that the position is now a regular butterfly, like the one we reviewed at the beginning of this discussion.

The advantages of this approach are that:

1. All risk is removed from the position.

2.The position has a slight posibility of making a very large 100% additional profit.

3. If the broker charges a fee to close each contract, it is cheaper in fees to roll up one contract than to close all four contracts.

4. Sometimes it is easier to get an order filled to roll the lower strike than to get an order filled to close all the positions at once.

It typically costs a little more to roll up the lower strike to create a free butterfly than to close the whole thing, but usually not much more. Another consideration is that for this roll-up to make sense, the price of the underlying asset will have gone up, so the probability of it dropping back to a profit at expiration is very low. But there is a possibility, so I think of it as a lottery ticket. I’ve done this a number of times with this trade, and have never hit the “lottery” with a fall back to the profit area of the butterfly. Maybe someday.

Final thoughts

There are many ways to set up butterflies and broken wing butterflies. The methods I describe here are in line with my philosophy of trading and risk/reward expectations. Many people trade butterflies aggressively aiming for the big reward, but I’m more excited about the rapid decay when the price is away from the strikes.

I’ve been very successful with this trade, and made a 500% return in a year in one account only trading this strategy. I wrote a post on this experience that you can refer to. However, I was using most of the capital in the account, compounding my winnings, leaving myself without a lot of wiggle room. Losses can be quick in this trade when the market turns against me, and rolling requires doubling up on capital to stay in the trade. While I was able to recover every one of these positions, many times it looks weeks or even months of rolling to get out whole, tying up capital along the way. So, someone trading this strategy has to be prepared for situations where a loss can occur and have a plan of defense. I’ve explained my logic for stop, roll, or hold, but it is emotionally hard to maintain a position that is showing a loss of 50% or more of the capital at risk. I’ve learned that if I plan to roll losers, I must have plenty of capital on the sideline to add when the debit side is closed and the capital requirement doubles.

Most of the time, this trade is just easy money, but the tested positions can get very dicey especially when trying to hit the mid-strike. So, I’ve lately used the broken wing butterfly more when the market is down, and use a slightly different version, the broken wing put condor, when the market is at highs. And in true bear markets, I often use the 1-1-2-2 put ratio trade for more protection.

Of all the trades I do, this one is the hardest to explain, even to experienced option traders. So, this is one of the last trades I suggest to new option traders. Don’t feel bad if it doesn’t make sense at first. My suggestion to someone considering this trade is to set up a one contract trade and use a stop loss to prevent a big loss. After seeing how the trade works a few times, consider other management techniques.

Ideally, I open this trade on a Friday with 21 days left to expiration. Then, I close it two weeks later with 7 days left to expiration and open a new position immediately with 21 days left. It isn’t exactly continuous rolling like many of my other strategies, but the idea is the same- to profit continuously from time decay. For me, this just works.

You write very well. It would have been even better if you had used some more examples explaining how you manage losers.

I love this strategy myself as well.

I have developed a scanner and alert tool for this specific case and wrote an article about it.

https://www.ninjaspread.com/flat-spx-broken-wing-put-butterfly/

Little confused on your tp, sold one for $43 credit on xsp, what would be your tp… great site by the way 👍

Darren- Thanks for the kind words.

These days, I typically try to sell for about 10-15% of the risk/buying power required and try to close for 2%. So, if I sold an XSP BWB 3×6 ($3 risk), I’d want to sell for 0.30-0.45. I don’t know if this is the trade you put on, but since you collected $43, that sounds like 0.43 per unit. So, in total money that’s likely $43 sold against $300 risk. I’d want to buy back for 0.06/unit or $6. If I opened at 21 DTE, I’d like to be out by 7 DTE.

To be clear, when I say 3×6, that’s a debit spread of 3 and a credit spread of 6 wide, say +389 / -2×386 / +380, or something like that.

Can you explain what you mean by “close for 2%” of the width? I see we take our premium credit divided by the max loss, which should equal 10% or more of the width of the narrow wing. By “narrow wing” does that mean the upper strike minus the lower strike (101-98) or the width of profit at B/E at expiration? (B/E looks like about 98.5 at expiration). So if premium credit is 12% (credit-max loss) for example, and you buy back 2%, you keep 10%…I’m confused by what that means…how do you “buy back” 2%? I’ll try re-reading but hoping you can tell me percent of what.

Good question. The numbers and concepts can be a bit confusing. Let’s take an example to illustrate the math.

Let’s say we open with a broken wing butterfly in SPX with strikes of selling 2 put contracts of 3950, and buying a contract each of 3975 and 3900. So, there’s 25 points between the upper long strike and the short mid strikes, and 50 points between the mid strikes and the lower long strike. Some would say this is a 25×50 wide broken wing butterfly. So where is the risk in this trade?- At expiration the position is in the money below 3925, so we have 25 points at risk- we could lose up to $2500 less our premium collected. So, when I refer to the width of the trade, in a broken wing butterfly, I’m really interested in what the risk width is. It’s a bit of a carryover from simple spreads, and honestly a bit lazy on my part, because there are two widths- the width of the long spread (25) and the width of the short spread (50). The risk is the difference in the widths. Since my typical trades have the short side twice as long as the long side, it’s fairly easy to come up with a width that represents the potential losing side of the trade. So in this case, I’m saying the width is 25.

So, to collect 12% of the width, we’d want to get $3.00 premium, which assuming the strikes are around our target Delta values, we should be able to achieve. Remember, we choose the strikes that meet our targets and we decide when to enter- nothing forces us to take less or enter at a time we don’t want to.

The goal of closing for 2% of the width would mean that we would buy back all four option contracts for a net 2% of the 25 width, or $0.50. So, we want the position that we collected $3.00 with 21 days to expiration to decay to $0.50 by 7 days to expiration. Our profit would be $2.50 in premium, or $250 for the contract, which is 10% of the 25 width, or the $2500 risk.

Technically, we only have $2200 at risk because we collected $300 at the start of the trade and if the end value was a debit of $2500, we would still have the $300 we started with, so a net loss of $2200. But for short hand calculations, I still find it more useful to look at the width of the risk separate from the premium I collect for quick back of the envelope analysis when entering and exiting. So, if you hit the targets, your true return is $250 on $2200 risk, or 11.36%- it’s actually better! But I needed a calculator because I couldn’t do that math in my head. My shorthand calculation underestimates the upside slightly and overestimates the downside percentages. The difference in this case is fairly small, and for me it’s close enough for thinking through the mechanics of the trade.

I hope that answers your question. It gets a bit complicated, and often it often helps to make some simplifying assumptions that make the math easy. With a background in engineering, formulas can be overwhelming, and it is often useful to use rules of thumb that get an answer that is close enough when precision isn’t critical. In this case, it’s a concept- every trade is slightly different and you aim to get as close as possible to your targets, following a plan.

Hi Carl,

How much of the capital in a given portfolio do you typically use for this position – do you keep any cash in reserve for rolling/defending the credit spread?

Thanks for publishing this – I have always wanted to find a way to employ the Tastyworks butterfly but never found a “battleplan” I liked. Great read.

Thanks,

Bryan

Bryan- Thanks for the nice comments.

You bring up a great point on maintaining a cash reserve. While this is a high probability trade with defined risk, it also can lose a lot on occasion. We don’t know when those occasions will be, so we always have to be prepared. How much to set aside partially depends on how much portfolio volatility a trader can tolerate on a percentage basis, but also on the diversification of strategy and underlying securities. For the broken wing butterfly, a big consideration is management strategy for tested positions, and the capital implications. Cash reserves have to be in place to account for worst-case scenarios.

If a trader stops out a position when tested, the loss is limited to the amount set by the stop. The account has that amount less capital for the next trade. Many traders look at situations like this and back-test to look for the maximum drawdown to determine how much capital might be needed in bad times.

If a trader wants to roll a tested broken wing butterfly into a spread, the capital required approximately doubles for the trade. For example, a 25×50 wide BWBF in SPX would require $2500 minus credit received in capital, but when rolled to a 50 wide spread, it would require $5000 capital minus the credits received. So, the capital requirements can expand quickly. If an account were doing the trade exclusively, having less than 50% cash reserves is a ticking time-bomb. And that doesn’t take into consideration the maximum drawdown impact if the rolls don’t recover, or losses pile up one after another.

This is why most people try to keep 50% or more of their options capital in cash reserves. These days with short-term interest rates of 5%, we don’t need the cash to be just cash, but it can be in interest bearing cash funds that can easily be accessed in a day or less. I recently realized I had way too much cash sitting in my account not getting interest and bought no commission 5% funds that compound daily.

The higher up the risk ladder we go, the more important it is to have cash available to provide stability and buying power in a crisis. The big irony is that the time you need to be hanging onto cash the most is when everything looks great and volatility is low. Volatility spikes can really do a number on positions that are based on net short option trades. So, it makes sense to up your cash when the market is quiet, and get more active when the market is in chaos. That goes against our emotions, but all studies show that particularly for options, this is the best path for hanging onto your capital over time.

The only exception is covered option trades with covered calls and cash secured puts. These have less volatility than stock alone, so we can treat cash reserves like we would for an all stock portfolio. The cash for cash secured puts is a forced reserve, so it really isn’t extra cash from my perspective.

Long term success in the market isn’t about how much you make in good trades, but much more so about how well you can preserve capital when the losses come.

Great article, thanks for all the detail. I really like a lot of Tasty’s approaches, but not this one. I’m not crazy about the free butterfly approach, or their wanting to enter these at 45 DTE. I’ve also recently been trying putting on broken wing butterflies at around 7-10 DTE, collecting a lower credit and playing at a small shot of getting close to max profit, but that’s been inconsistent at best. It ends up being either too small an initial credit, or so close to the money that there’s a decent chance of going through all the strikes for a max loss.

I also appreciate your thoughts on sticking with puts and indices, along with the 21 DTE. I’ll be trying this for sure, thanks!

This post is awesome. When u say 32/28/20, do u mean for example selling the (2) put at 28 delta, and buying each of the put at 32 delta & 20 delta respectively? Or u meant something else? I might have misunderstood…

Thanks for the kind remarks. Yes, buy the 32 and 20 Delta puts and sell two of the 28 Delta puts. You got it!

I’m curious Allen, have u tried it on the IWM or RUT or QQQ? Does this 21 Day Broken Wind Butterfly work well on those too?

Good question. There’s a trade-off with RUT and QQQ. There is more Implied Volatility and more premium which is good. The products are lower priced, except if you use NDX for your Nasdaq 100 options. But that higher IV is because they move a lot more than the S&P 500. In a bull market, all of these things can be great, but in a choppy or bear market, a broken wing butterfly can go into the money more quickly and unpredictably- at least that’s my experience. But trading all three provides some diversification to different parts of the market, as long as you realize that they are all market indexes that have a fairly high level of correlation, and when the market goes down, they all go down.

Have you tried doing this on mini’s? I’d have to assume there’s not a lot of difference? or is that not the case? Very cool writeup.

Sure, you can do this on /ES, but brokers won’t generally allow three legged orders on futures options, so the order has to be made in two parts. Also, you can’t set a limit order to close all three legs, so only a limit order to move to a equal wing butterfly would work to take off risk early. You’ll get some span margin relief on buying power, but this is defined risk to start with and so buying power is mostly defined to start with.

You can also trade XSP or /MES, but watch trade costs and liquidity.

Also, are you still using this method? Has it been successful over time?

I still use this method and it works well most of the time. The only time it has issues is in down markets. As I write this, we’ve had a bit of a decline in the markets over the past few weeks and I had to do a defensive roll on a couple of these trades that were nearing expiration with the short strikes in trouble. But since these positions are a small portion of the account, I have capital to work with and the impact is small on my total account.

One big watchout to remember is that to roll down and out on the credit side when closing the debit side is that more capital is required. So, a trader can’t have all capital tied up in this trade, or a downturn could wipe out an account quickly. A total loss is very possible in a steep downturn, so this is not a trade to put all the eggs in one basket.

This trade can go for months and months without a single loss, and then have a situation that wipes out everything earned.

I often add positions on days when the market is down and volatility is up to have more room for future downturns. It seems like the trades that get tested most were those that were opened on days when the market was trading near an all-time high.

Fantastic. I’ve been reading a lot of your posts on this site and got into TastyTrade which is significantly more user friendly than Etrade for these because I can set the profit target and stop losses automatically. I’m curious how often you’re putting these trades in action? With the BWB and the Broken wing Condor (not quite ready for the 1122) are you liking to put in one of those (BWB or BWC) on every Friday if it looks right? Are you adding some midweek? Do you ever put a BWB and a BWC on at the same time?

I generally try to add a BWB position each week. I try to wait for a down day and then pick the Friday closest to 21 days. Lately, I’ve been using mostly BWB in SPX with 20 x 40 wings, collecting a little over $2.00 premium with a closing target of $0.35. I could probably have used BWC more in the last few months with the market so high, but hindsight is 20/20.