What does it take to roll a short put every day for credit while hedging with a longer put to protect against big downsides? Can a long put really protect a short put in a diagonal spread? Is the reward worth the risk? In this “Daily Diagonal” Trade strategy, we’ll delve into how to optimize selling a “Poor Man’s Covered Put” and rolling it for credit every day.

This trade is a diagonal spread. The two options expire at different times and are at different strikes. Spreads with the same expiration and different strikes are called vertical spreads, and spreads with the same strike prices but different expiration dates are considered calendar or horizontal spreads. So, a diagonal spread is a combination of calendar and vertical elements.

What is the point of this, you may ask? Well, long duration options generally decay slower than short duration options. So, if we sell a short duration option, while buying a long duration option, we expect the option we sold or shorted to decay faster than the option we bought or hold long. Excluding all other impacts, time should make this a winner for us. But of course, we can’t exclude all other impacts, which is why we need to understand the ways the trade can go against us and what we can do about it.

I’ve been asked what can be done to reduce the amount of capital required and possibly increase the returns on diagonal trades, especially in comparison to the Very Long and Very Short Diagonal Put Trade, written about elsewhere on this site. As mentioned there, reducing duration will reduce the cost of buying a put, but there are some trade-offs to balance. This article is written to illustrate those trade-offs, so traders can choose optimal strikes for a diagonal put strategy.

Isn’t selling a “covered put” backwards?

Most option traders are familiar with the process of selling a covered call. Someone owns stock, and sells a call that is “covered” by the stock. If the stock goes up a lot, the call seller may have the stock “called away,” and be forced to sell their stock at the strike price of the call. The reward for this is the premium collected and the possibility of keeping the premium if the stock doesn’t go above the strike price by expiration.

Some traders find that buying a stock to sell a call against it can be expensive, so there is a well-known diagonal trade that many describe as the “Poor Man’s Covered Call,” which is written about elsewhere on this site. This trade typically buys a deep in the money call with a long duration as a substitute for stock, and then creates income by selling out of the money calls against it with shorter duration. It’s like a covered call, but the trader only pays a fraction of the cost of stock, thereby making it a “poor man’s” covered call.

One issue I’ve always had with the poor man’s covered call, and covered calls in general is that I’ve found the short call being sold isn’t a high percentage winner. In fact, in the majority of cases I’ve studied, particularly with indexes and index ETFs is the call loses more than it gains, because the underlying goes up more than the premium collected, so while I like the idea of collecting premium against a long stock or long option, it just isn’t as good as percentages would predict. Additionally, skew impacts the poor man’s diagonal version by having significantly higher implied volatility on the lower strike long call than the higher strike short call, so there is less premium to sell and more premium to buy.

What if we use puts instead of calls? What if we trade a poor man’s covered put? Just the concept of this takes some time to grasp. For this trade, we start by buying a relatively long-dated put, a bearish bet that the market will go down in most situations. You may wonder whether I need to really think the market will be lower in the future to buy a put? Aren’t buying puts the worst probability option trade there is? The answer is that we don’t plan to hold this option to expiration, and we aren’t buying this to be bearish. We are buying this as a hedge to protect us when we sell a put. We’ll tackle all the negative points of buying a put as we dig deeper into managing the trade.

If we sell a put naked, we are exposed to all kinds of risks, virtually unlimited risk. But, with the purchase of another put with more duration, we limit our risk substantially. We don’t eliminate risk, as we’ll discuss later, but we limit it.

The money maker of this trade is selling the put. As we’ve discussed other places on the site, selling puts is a high probability trade. It is a strategy that typically does better than probabilities would predict. But it comes with tail risk that needs to be accounted for. That’s what the long put is purchased for, to protect the downside. The details are in the Greeks and in the management of the trade. Let’s get to it.

The Initial Setup

In this trade, I pair buying a put 60 days from expiration with selling a put 3 days until expiration. The short option with three days left is expected to lose nearly a third of its premium value in a day, which is to our benefit. The long put is expected to lose less than 1/60th of its premium value in a day, a loss that goes against us. The net of this trade should be a daily gain due to the difference in decay, more on the short side than on the long side.

Why three days and not one? One day until expiration would lose almost all the premium, so why not? A couple of reasons- 1 DTE can be harder to manage and profit with bigger moves, and also avoiding pattern day trading. There are work-arounds for these, so if you insist on selling the shortest duration put possible, nothing is there to stop you, but I find it a bit too challenging.

On the long duration put – is there something magical about 60 days? Not really, but I find it far enough out that time decay is still slow and I don’t have to adjust it constantly, but not so far out that it gets really expensive. The long put defines the capital required for the most part, so the one chosen is important for considerations of risk and return on capital.

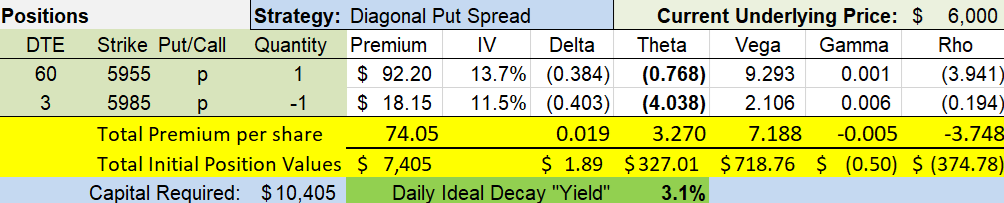

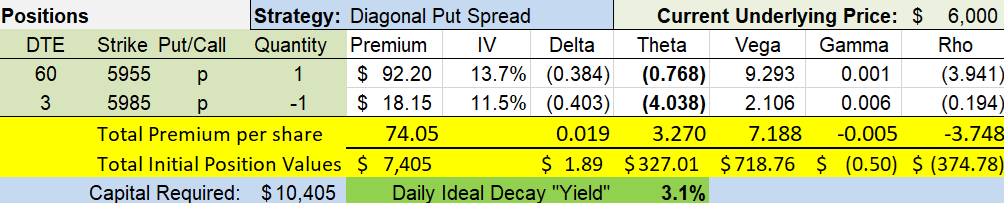

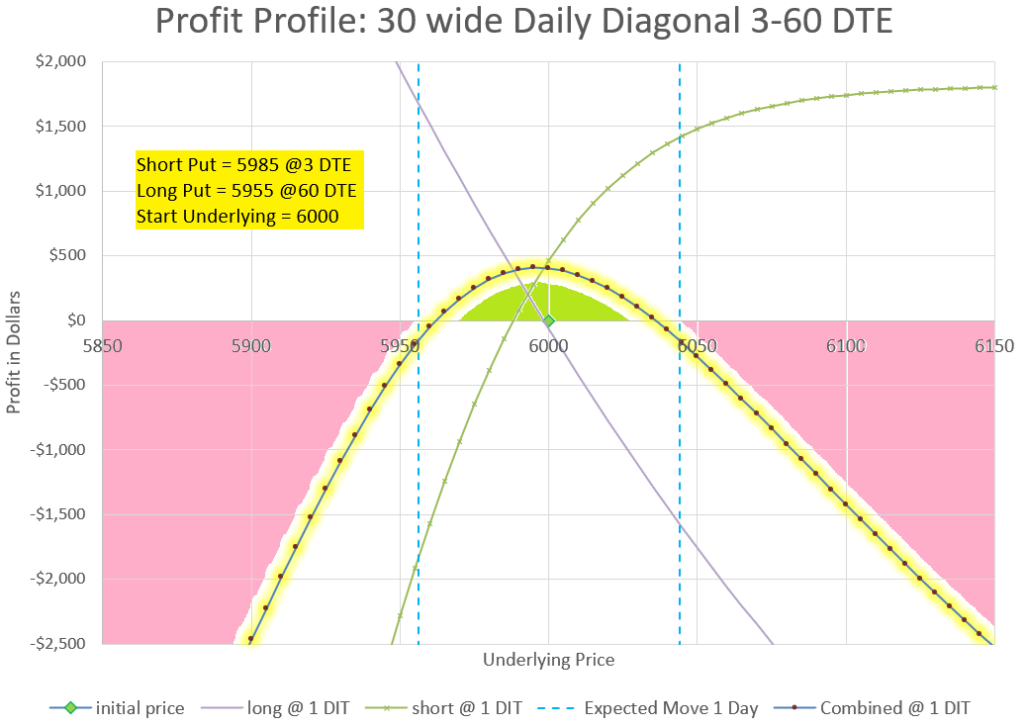

Let’s take a look at the set-up for this trade:

One thing that should jump out in this table is that Theta is $327 per day on $10,405 in capital. That’s a 3.1% potential return per day from decay. While we can’t expect to keep that much every day, it’s a big potential amount.

You might wonder why the capital requirement is $10,405. We are paying a net $7405 debit to start, which normally is the amount of potential maximum loss. However, because our long strike is lower than the short strike by 30 points, we are taking on 30 points of additional risk, or $3000. Add those together to get $10,405. Different brokers may choose to require somewhat different amounts of capital for a trade like this, as diagonal trades don’t have straight-forward risk based on strike prices due to the difference in expiration. Consult your broker for specific capital requirements. I’ve found this can be especially tricky at some brokers if you have other option positions in the same underlying that expire between the two sides of this diagonal- broker software gets confused.

If over $10,000 capital for a single contract spread seems like a lot, there are some possible ways to reduce this cost, with some trade-offs. Probably the simplest is to use SPY, the ETF, for 1/10th the cost, but there is assignment risk and dividend issues to be concerned with. You can use long strikes that are the same or greater strike price than the short with higher Delta. Or go with shorter duration and take on a bit more decay. So, don’t let the price tag scare you away just yet- see how this trade works and why, then decide if there is another set up that you prefer. And, if you think this is a lot, compare it to its cousin, the Very Long and Very Short Diagonal Put trade that requires $60,000+.

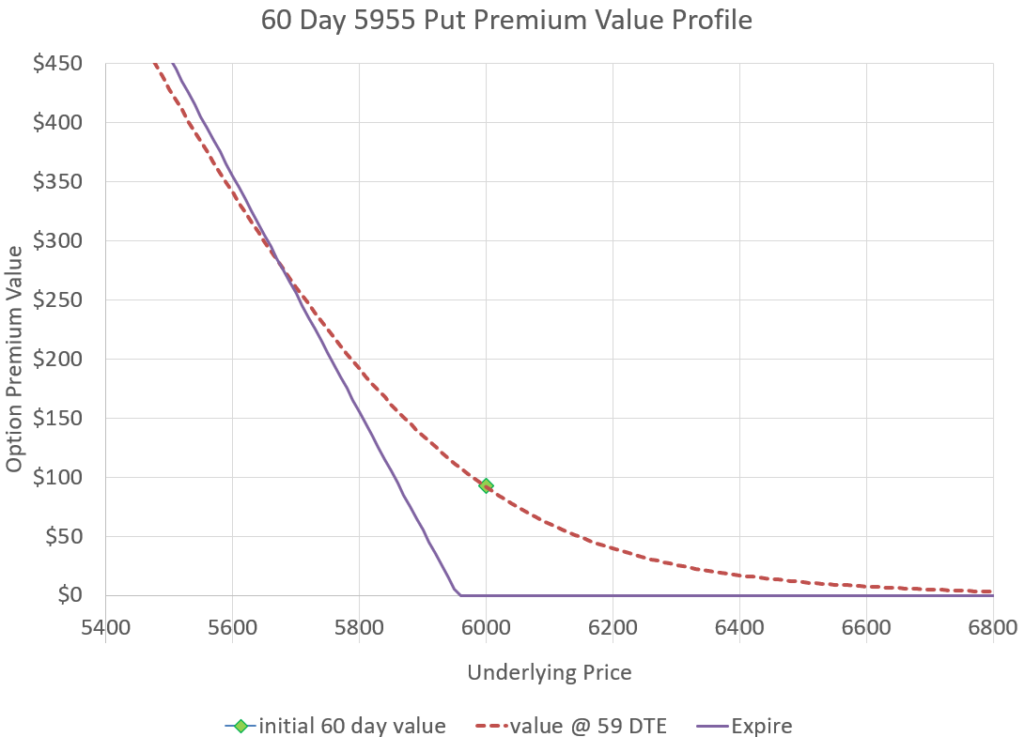

If we stick with the 60 day long strike selected in the set up, we can see the difference below in its value after a day, compared to the value at expiration. Since we don’t plan to hold until expiration, we should just note that the one day later values far from our current price tend to approach the expiration value, while the values near our current underlying price have quite a bit of extrinsic value, turning the angle at expiration into a gentle curve at 59 DTE.

Notice that the premium curve for our long strike is very different from where the premium will be at expiration. The slope of that curve illustrates the Delta value, showing that at this point in time, the option premium will only change about 40 cents for every dollar in underlying price movement. Notice that the premium curve does bend toward expiration, which means there is some Gamma influence. Delta changes when the underlying price moves a fairly significant amount, but for moves of 100 points or less, the change in Delta is fairly small. For every dollar change in the index, the long put will move around 40 cents.

One would think that implied volatility would drive the premium value of the long option, as the Vega value is very high as well in the table. Implied volatility does change, but at slightly less of the rate of changes in VIX. So if VIX moves from 25 to 15, the IV of the 60 DTE long put deep in the money might move from 23 to 17 in the same timeframe. So, Vega in this trade can boost the long strike some when we need it, but also cause the value to drop a bit extra on up moves.

When we pay over $90 premium, you might think that there would be a lot of Theta decay, you’d be right. Notice that the Theta decay on the long is about 1/5 of the Theta decay on the short, so a substantial amount, and a value to keep an eye on, but much less than the short strike’s decay.

The long put of this diagonal trade is a buy and hold position most days. The key value that I’ve only mentioned in passing is the Delta value of approximately 0.40. I’ve picked this to match up with the short strike Delta for an overall position that starts at Delta neutral. But we will see that while the Delta of the long is somewhat stable, the other option in the trade is not. The bigger reason to adjust the long strike is to manage the amount of capital needed when a short strike gets rolled. So, we’ll have to pay attention to the long on a fairly frequent basis, just not necessarily every day.

Short Option Considerations

We will quickly see that the short option, the one that we sell with 3 days until expiration, behaves differently than the long option. In many ways, that’s on purpose. With expiration just a few days away, we are trying to collect a nice premium, see a bunch of it decay, and do that over and over again, day after day.

Let’s look at the setup data again, this time focusing on the second option, selling a 5985 at 3 DTE.

We are selling an option 15 points out of the money and collecting $18.15 in premium. The Theta value says that we expect to have $4.04 of that premium decay in one day, so almost one fourth should disappear over a 24-hour period. What we will find with this side of the trade is that the key Greeks that drive this option’s premium are Theta and Gamma. Vega and Rho generally don’t matter, there isn’t time for them to do much. Delta will change as Gamma changes, and throughout the day, Delta will drive the option price up and down as the underlying index changes.

If you trade this strategy, you will quickly learn that the amount of premium available each day can vary significantly, based on what is scheduled for each day in the future. If the Fed is making a rate announcement, IV for that day will be increased and there will be a lot of premium for the day of the announcement and the days following. Same for jobs numbers announcement days, inflation announcements, and sometimes other big events that are coming with uncertain outcomes. So, while I said that Vega has little impact, the implied volatility for each day can make a big difference in prices from one expiration day to the next. Vega, the change in implied volatility, on the other hand, doesn’t typically have much impact during the trading day, except at the moment where big scheduled announcements occur. For example, once the Fed finishes its announcement, expirations after that drop in implied volatility for the next several days of expirations. This may impact your choice of which expiration day to be in before or after the announcement, and when to roll out to a later expiration.

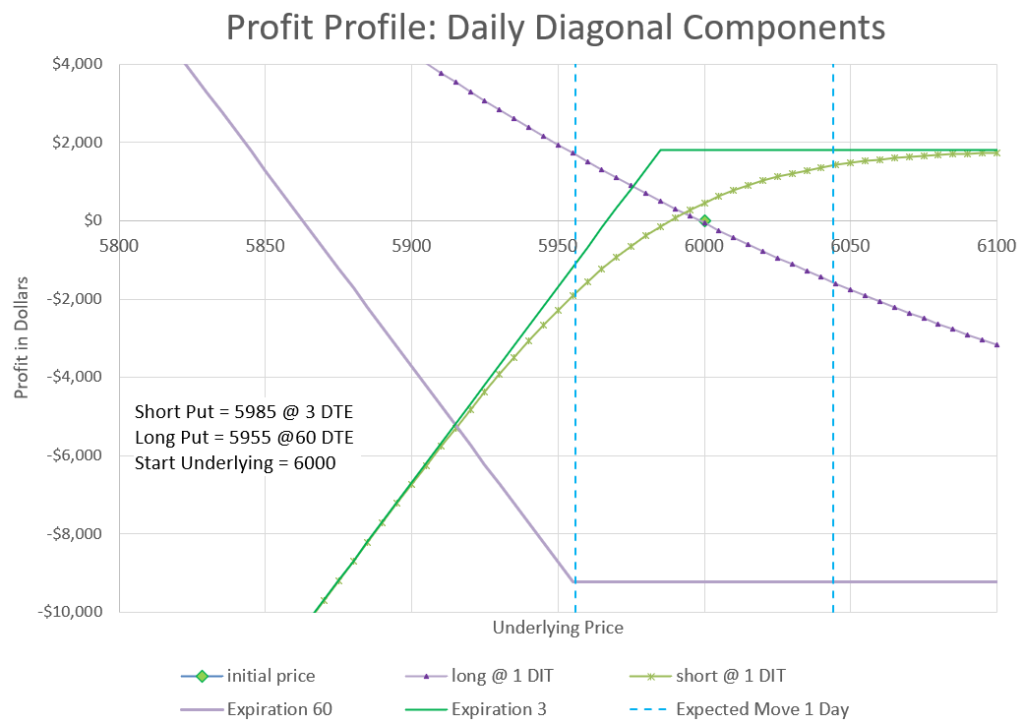

Another thing that is important every day is to understand the valuation curve of the short option and its relationship to the expiration value. While the long option seems to have almost no relation to the expiration value, the short option quickly hugs the expiration value with any significant move up or down in price. Let’s look at a comparison in this chart at prices near the money. We can zoom in a look at how the short put value profits or loses after a day, compared to the long put.

I’ve basically added the short put’s profit profile to the long put’s profit profile, both for a one day move, and at expiration. I’ve also added lines to show what a one day expected move is for the index. What should be clear is that the short put quickly matches the expiration values for about any move outside the expected move. Inside the expected move there are some differences as we are comparing a one day change to a two day change.

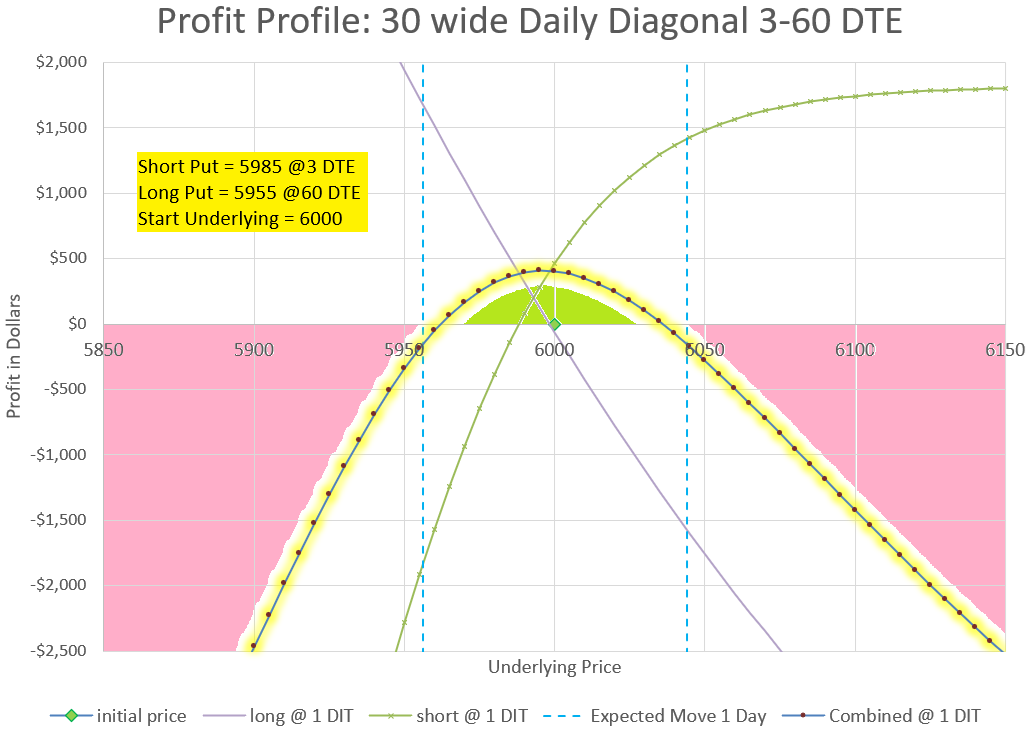

If we zoom in far enough and add a line to show the combined profit and loss of the trade after one day, we can start to see the appeal of the trade.

Now we can finally see how the profit and loss of each option combine into a strategy where we expect to profit very often. But, we can also see that moves that are bigger than expected can lead to very big losses. I’ve colored in the profit area in green and the loss area in red/pink. I’ve listed the current price, option strikes and expirations for reference, and again showed the expected move.

Next, we’ll discuss the basic mechanics of managing the trade, both on good days and on bad and very bad.

Basic Trade Management Day to Day

Because the long put is farther out in time, it requires less attention, even though its value fluctuates with changes in the underlying index, as well as implied volatility. When buying a 60 DTE option, it can be left alone for days or weeks at a time.

The main action is on the short put of the diagonal. Because it is just a few days away from expiring, it needs attention almost every day, if not twice a day. There are many choices of variant ways to manage, with trade-offs. Some trade-offs are comfort with a style of trading, while other choices have a big impact on results.

One question people often ask is what time of day should the position be rolled? It isn’t critical on inside days, days where the move is inside the expected move. But, it is good to be consistent, and there is more decay by afternoon than there is in the morning. Because we are rolling before expiration, we have some flexibility to work around other things in our schedule, especially on inside days. On big up days, it may make sense to trade in the morning and possibly again in the afternoon, as we’ll discuss when we get to that scenario.

When I first came across this trade, it struck me as a way to essentially sell a naked put, manage it by rolling, but have a hedge to protect it. After trading this strategy for a while, I find that initial viewpoint holds true. For me, this trade works well for me in every preference I have for trading. For other traders, this trade might go against every instinct they have. So, let’s get to it, starting with the easiest situation to the hardest.

Inside the Expected Move

On the profit chart above, notice the dashed lines of the expected move. This is showing the one day expected move of the index at the Implied Volatility levels that were established when the trade was started. We expect to stay inside these lines 68% of the time. Notice that we have a nice green profitable area mostly inside the expected move. We’d like the market to stay in this area every day, but that won’t happen. However, 2 days out of 3 isn’t bad.

What happens on these green days? Simply said, the short put decays and the long put doesn’t change much. You can see from the profit lines of each option, that small moves cancel each other out between profit and loss of the long and short. We start the trade with premium in the short put that will decay significantly in a 24 hour period if the market stays the same or goes up.

Managing on green days is easy. Just roll out the short put by one day. If we started at 3 DTE, we wait a day until 2 DTE, and roll back out to 3 DTE again. We should be able to collect a nice premium for the roll. So, let’s say we started with $18.15 as in our example at 3 DTE, and market barely moves. Let’s assume our short put is worth $14.00 after a day. For our roll, we buy the 2 DTE for $14 and sell a 3 DTE put for $18.00 to replace it. Let’s also assume that the long put didn’t change in value, so our net profit for one day is $4.15 premium, or $415 for the full contract. And we collected another $400 that we hope to lock in tomorrow. Since I have about $10,400 in capital tied up, my one day return is right at 4% on this ideal day- not too shabby.

Which option should we roll to? The market hasn’t moved much, so our strike price probably won’t move much. For the purpose of this trade, I’m trying to sell a put with approximately 0.40 Delta value. If the market went up a little, I might sell my next put at a slightly higher strike price, and if the market is down, I may need to see a slightly lower strike price. Why 0.40 Delta? Because the long put has a Delta of around -0.40, the combination is then Delta neutral. I’m not trying to predict which way the market will go, I just want my position to be affected as little as possible by moves in the market.

Days Up More Than the Expected Move

Normally, I’m excited and happy when the market goes up a lot. As discussed elsewhere on this site, the market has a normal upward bias, it tends to go up more over time than it goes down, so most strategies need to try to take advantage of that. One would think that since the “money-maker” of the trade is the short put losing value, and the short put loses value when the market goes up, we should make money on big up days. But we don’t. Because this is in reality, a bearish trade. Our long put is bearish and when the market goes up and up, the long put goes down and down.

The problem with big up days is that the short put only has a limited amount of premium to lose or for us to profit from. In our example, we start with $18.15 in premium with 3 DTE. That is all we can make from this contract leg. If the market jumps up 150 points over night, the market might open with our short contract worth $0.10 or $0.05, while our long contract went down in value $60 in premium. That’s a $4200 loss net. Worse yet, there really isn’t any way to get it back quickly. As I write this, I’m reminded of a recent event, the 2024 presidential election, where the market went up 15o points overnight. I had rolled down my short strikes the day before with huge IV and lots of premium in the market. The market was preparing for a long, drawn out vote count that would cause huge problems, but by early morning it was clear that Donald Trump had won the election decisively, relieving the market of all kinds of contentious scenarios. I was not prepared for the big upswing overnight. The move set me back, losing a month of profits in one night.

The good news is that big up days aren’t that frequent in nature, and often come at times that won’t hurt this trade, after a big downturn. We’ll discuss that more in the downturn section, so keep the big up day in mind for that.

How can I say that big up days aren’t frequent? The market is in bull market mode almost 80% of the time, and when it is, it sets new high marks all the time it seems. However, what we tend to see follows an old Wall Street cliche that the market “climbs a wall of worry.” What this means is that usually as the market is steadily climbing there is always an underlying concern that the market is too high and any number of things might turn it around, yet there is also a sense of complacency. The worry keeps the market from going up too fast, while the complacency can lead to big downturns without any notice. Markets crash down, not up. For this trade, a big move of 2-5% can feel like a crash- moves this big in a day or a week are almost always to the downside. The biggest up days are usually the day after the market hits rock bottom and with this trade, we should be ready and waiting for that to occur. Instead, let’s talk about how we deal with day after day of 0.5 to 1.0% gains.

One quick little stat to keep in mind- when the VIX is 19, that equates to an expected move of 1% a day up or down. As VIX goes lower, the expected move comes down as well. If you trade this strategy, you’ll quickly see that premium changes a lot day to day, along with the expected move for the next day or two. Sometimes the market is anticipating a big announcement, earnings from a major company, jobs or inflation data from the government, or interest rate announcements from the Federal Reserve. We will see short duration options have much higher premium anticipating these upcoming events. That’s good for us, because we can collect more before events that have the potential to move the markets a lot. On days when nothing big is expected, there is less premium and we have less of a move to anticipate. When trading this strategy, you’ll quickly learn to watch for these big events and be ready to make a quick roll to get more premium if there is a big move up.

Let’s say a monthly jobs number is viewed favorably by the market. The announcement comes on the first Friday of the month an hour before the market opens. We know the announcement is coming and generally in the hour after the announcement, we can see how the futures market is trending and can anticipate where the regular market will open. If the market is opening up 40-50 points and my strike was 15-20 points out of the money at the close the day before, I can be pretty sure that my short put will open with a lot less value- this will be due to both an increase in price and a decrease in implied volatility.

If the market opens way above my short put, my goal is to collect premium and get into a position where I can have premium to decay. So, my standard reaction would be to roll up my strikes in the same expiration as I had to the strike closest to 40 Delta. Some traders may choose to sell a slightly lower Delta in case the opening move is over done so they can avoid be whipsawed. If the option is still two days out, there’s plenty of time to continue to manage it. Another choice is to go ahead and also roll out in time when rolling up- that way there is no need to roll out later in the day to stay at the target DTE for the short position. Part of the reason I’ve selected a 3 DTE short is to avoid rolling more than once a day. There’s pros and cons to what you choose, and I’ve found that each trader will determine a level of comfort with their version of management. The key is to move from a single digit Delta value in the short put to something close to the Delta of the long put, neutralizing price movement for the immediate future.

This is probably a good place to remind traders of the Pattern Day Trader rule, which can be triggered with this type of maneuver. If you execute four or more “day trades” within five business days, you will be flagged as a Pattern Day Trader. A day trade is when you open and close the same position during the same day. Pattern Day Trader status is not a good thing to be identified as. Brokers have no choice on this, it is mandated by FINRA, a government agency in charge of these things and is intended to protect small investors from losing too much money. Any account with this status will have significant limits placed on the types of trades that can be done if the balance in the account is less than $25,000. Since this trade requires less than $25,000 in capital, a trader could be trading this in an account that could be impacted by the Pattern Day Trade rule. But the point is that if you start rolling in the morning and then roll again in the afternoon, that’s a day trade. If you do it four out of five days, you are tagged a Pattern Day Trader for that account, and brokers and regulators make it very hard to get untagged.

If a day trade is such a negative thing, why consider it? Well, with this trade, notice that the profit curve of the short put goes flat at price movements beyond the expected move while the long just keeps losing. The only way I know to combat this is to roll up the short as much and as often as is needed to keep adding premium to decay. My goal with 3 DTE is to prevent the need to roll up more than once in a day to only the most extreme of situations, aiming to very rarely day trade. I also tend to roll out each day and each trade, so that I don’t have a reason to trade again the same day. But in unusual situations, I can still do a day trade, but I make a point of putting a post-it on my computer so I don’t trigger a Pattern Day Trade violation in the next 5 trading days.

I’ve traded the short side of this trade several different ways to see how each way works out from a number of factors including profit, risk, stress, and timing. Slightly longer duration is easier, but less profitable, which is probably a common theme for most every trade discussed on this site, especially when you read the comments of readers who seem to always want the shortest duration and can’t understand why that isn’t what I have shared.

What kind of profit can this trade make? What I’ve found is that in generally up trending to flat markets, I can make around $500 net profit per week per contract trading between 3 and 2 DTE. These are averages over months of trades, considering both the long and the short side of the trade. The long side loses, but the short side gains more. Some days and weeks hit close to the maximum, but some days and weeks are losers.

However, when the market goes down, profits essentially stop, and management gets more challenging. It can be a little challenging when the market is down for a few days, or it can be very challenging when the market goes down a lot for a long time. We’ll dig into these scenarios next.

Down moves slightly in the money

If we start at any point in this rolling trade with our strikes sitting at our ideal 40 Deltas and we have a move down outside the expected move, that means our short strike will end up in the money with a Delta of over 50. Theoretically, this should happen 40% of the time-remember that Delta serves as a probability among other things. So, this is going to happen very often. Even many inside days are in this 40%, a 20-30 point move down is into the money, but inside the expected move. As we’ll see the overlap works out with the same mechanics, but the moves a little further down are what this section is concentrating on.

The good news is that sense we are treating this short strike like a naked put, we should be able to roll out for a credit. In many cases, we should be able to roll down and out for a credit. So, my goal in this situation is to roll down as far as I can for a credit to get my Delta down to as close to 40 as possible. If I don’t get to roll down much or at all, that’s okay, I’m just trying to bide time until the market comes back, and collect what I can. Remember that when the short side loses, the long side is gaining, so even though the value of the short put may start climbing, the long put is also climbing. To be fair, the short will quickly start losing more than the long is gaining, and that can be painful, especially if this happens when the trade is first opened or when adding an additional contract.

Generally, this continues to be fairly easy to manage, rolling out, or rolling down and out each day while the underlying is within 1-2% of the short strike price, or 60-120 points in our example trade. I find it easier to make rolls earlier in the day rather than waiting to the end, but it isn’t a huge difference. Again, rolling between 2 and 3 DTE also makes this type of roll fairly manageable compared to shorter durations. The further in the money, the more challenging to roll down and out for credit, and eventually it can be challenging to just roll out for credit if we get too deep in the money with our short.

Moves deep into the money

You’ve probably heard it said, and you may have even read it on this site somewhere that you can always roll out a short option in time at the same strike for a credit. Here is an exception to this “rule.” This exception is a bit difficult to comprehend and will force us to choose between a few less-than-optimal ways of managing the trade when this occurs.

The problem is the issue of negative extrinsic/time value. I discuss this extensively in the very long 5 year version of this trade and explained how this was very cool to be able to buy 5 year puts for less than their intrinsic value. That can be nice if you are buying, but not if you are selling. And this situation occurs with deep in the money puts. It’s always there, but it gets worse when the market is down and Implied Volatility rises. At that point you may find that a put $200 in the money with 3 DTE is priced at $196 or so, and a 2 DTE strike is $198. Remember, at expiration all index options have to settle for cash, so the price for an expiring option 200 points in the money has to be $200. What gives?

When the market has taken a big drop, there is some anticipation of a rebound, so option buyers don’t want to pay full intrinsic value for a deep in the money option, even one that is expiring in the next day or two. Additionally, as the options get deeper in the money with short duration, trading volume is lower, and bid/ask spreads grow, making good fills hard to find. It’s just a bad combination. This situation should occur less than 20% of the time, but when it does, there has to be a plan.

So, what to do? I’ll present two choices, roll down for a debit, or go further out in time to get a credit. Both choices have significant downsides, but there is a silver lining in each. The long-term view is to realize that eventually the long strike that is only gaining 40 cents for every dollar the index goes down will have to be cash settled as well, so if a trader is patient and can avoid paying too much debit on the short side, eventually the money will come back, less the premium paid and the width of the spread. But let’s hope we don’t have to wait for 60 days for or more for that, and in most cases we are looking at weeks or maybe a few months of tough rolls until we are back in profit mode. Let’s look at how each choice helps us get our short losses back, and you can decide for yourself which strategy is best.

I should probably mention a third choice-one that many would consider a first choice- fold the whole position. Because the long put is implied volatility sensitive, there is the dynamic that when stocks fall, IV generally goes up substantially. If this happens significantly, there is the possibility that the long may gain almost as much value as the short, which could provide the opportunity to get out with a small loss even though the short put went deep in the money. Even if the long doesn’t gain nearly as much as the short side loses, many traders may decide that the prudent thing to do is close out and avoid the two choices I’m going to detail out. After all, the market may stay down for a long time, and as you’ll see, fighting to get to a position to make everything back on the someday upswing may be more effort than many want to take on. There’s nothing wrong with folding a position and looking for a better opportunity.

For traders that are up for a fight with this position, I present two competing choices of reasoning. One concept is that rolling down, even for a debit moves the short position closer to getting out of the money and more quickly gets the short to strikes that can collect and roll premium every day to make up those debits. Since we don’t know how long it will take for the market to recover, getting our strikes at least close to the money can allow us to roll for credits that actually have daily decay. So, pay to re-position and then start making money again.

Another concept is that the goal with the short side is to always collect money from a roll, and that eventually all that premium on the short side from being in the money will be eliminated when the market comes back. Earlier, I said that markets don’t crash up. The only exception is when the market bottoms out and comes roaring back up. It’s virtually impossible to predict when a correction or bear market will end, but one characteristic of down markets is violent moves both down and UP! One of the worst moves would be to be positioned out of the money on the day the market jumps up 2-3% overnight because of some event that shows the worst is over. As we’ve discussed, when the short put of this trade is out of the money it has a limited amount of premium to contribute as profit, while the long side has almost unlimited amounts of capital to lose in a short period. Chasing the market down with this diagonal style position could end up a big loss going down, but a bigger loss coming back up. By finding ways to collect premium while the short is deep in the money, a trader will not get whipsawed at the bottom- all that premium sitting in the deep in the money short put can be gained back, eventually.

Either way, we also need to think about how to manage our long. When it gets deep in the money and time passes, we’ll need to re-position from time to time.

There’s pros and cons to each choice, so we’ll talk through the mechanics of each. There’s no right or wrong answer, just choices that are quite imperfect.

Rolling Down for a Debit

This is actually the easier choice to understand. It’s pretty simple. Every day that your position is in the money, roll out to the next day and roll down your strike 10 points. That’s 50 points in a week or just under 1% at current SPX pricing of approximately 6000. Most days this will cost around $10 debit, some days a little more, some days less, mostly depending on the market and how it impacts very short term Implied Volatility. Depending on how far down the market is, this may take a while to get the short strikes down to the current price.

You may find on big up days or days when an announcement is coming that you can roll down more than 10 points for a credit, if that’s possible, take advantage. The goal is to steadily get the short strikes down close to the current price of the index.

Once the short strikes are close to price of the index, we can go back to managing like normal. If all goes well, the short position can be ridden up and down with the market.

With market volatility high and prices down, my preference is to avoid getting very far out of the money, so I don’t mind being in the 50-60 Delta range in a down market. I wouldn’t pay a debit to get below 60 Delta. Remember that there is a possibility of a big upswing at any time and one has to be ready to aggressively roll up in that case, like we’ve already discussed. I also don’t want to have more Delta on the long put side than the short put when the market has the potential to rise quickly on a reversal, so I watch Deltas on both sides of this diagonal trade when prices are down.

If we use this strategy, we are more likely to need to roll down our long strikes as well to stay Delta neutral or close. We can also use these moves to close any gap between the long and short strikes.

So to summarize, the mechanics are to steadily roll down strikes, paying what is needed to get the short strike close to current prices. We don’t want to overshoot down. We have to always be prepared for a reversal, to aggressively defend any up moves. The difference is that on down moves, our premium serves as a big buffer for moves back up until we get close to the current price. When we have no premium buffer, we have to generate premium.

Finding a Credit to Keep Collecting

Ideally, we would like to just roll out each day and collect a little premium until the market brings the underlying price back up to our strike price. When we are less than 100 points in the money, this is usually fairly easy to do. But as we get deeper in the money, we start running into the nasty impact of negative extrinsic value. When this happens, the premium of a day longer option at the same strike is actually less expensive than the one we already own. So, rolling out would require a debit. This isn’t something we want to do day after day, as it is a losing proposition and the whole goal was to make money off of the short side of this diagonal position.

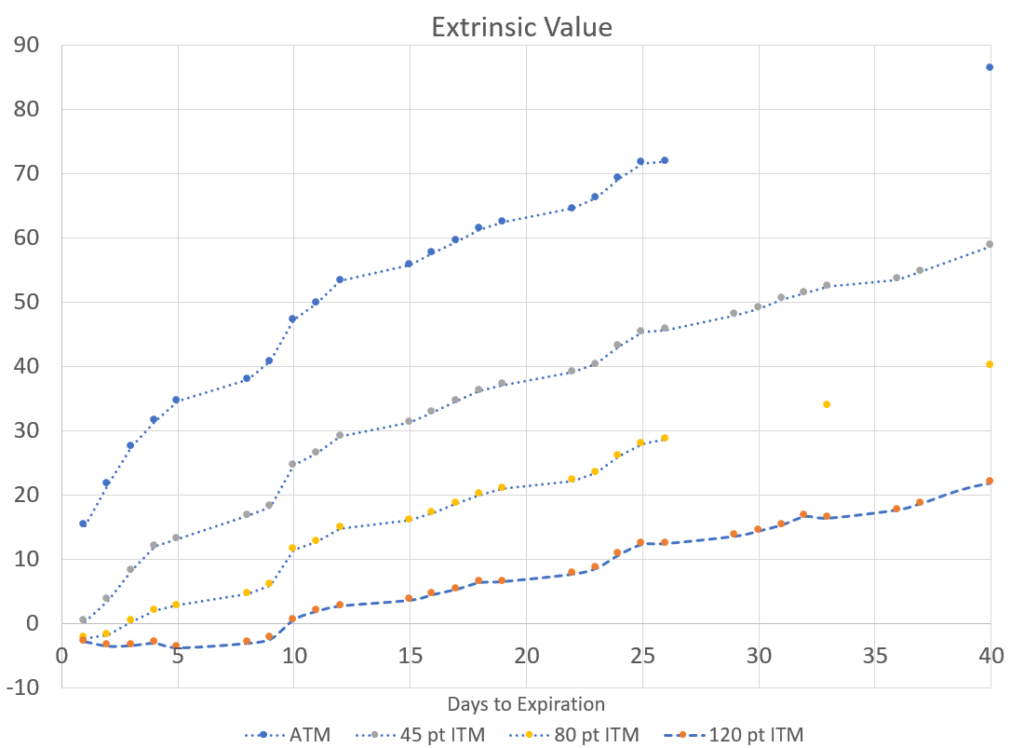

To give a sense of how this plays out, here is a snapshot of the data from actual option prices of puts at different DTE and different strike prices.

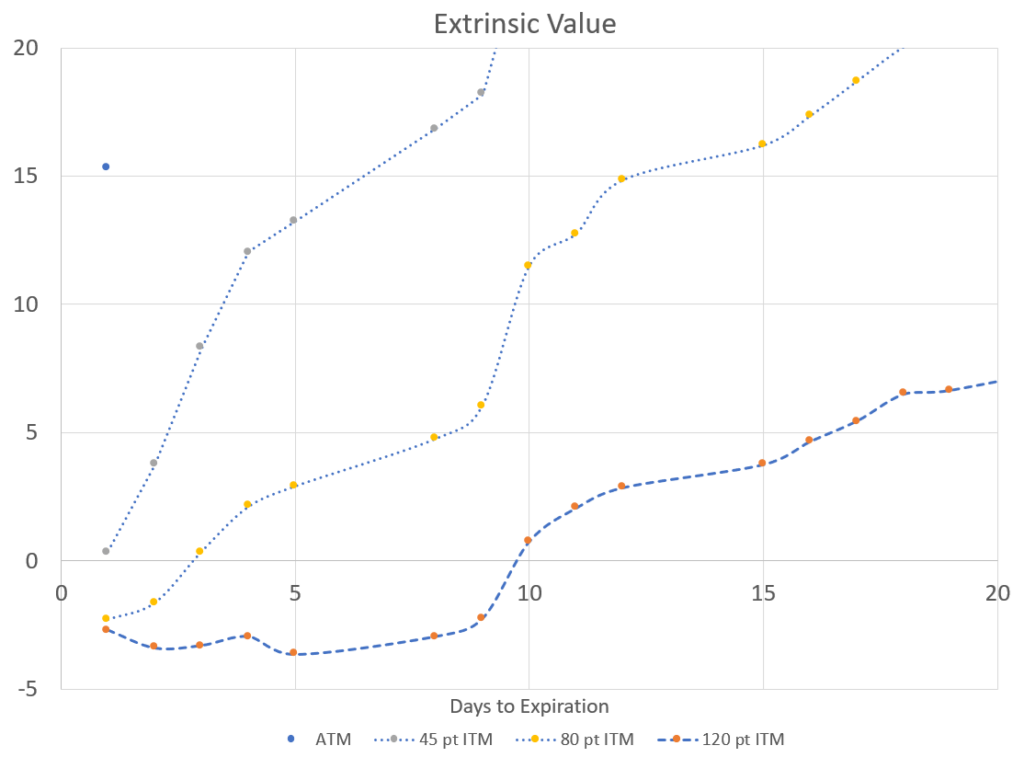

Notice that strikes at the money and a little in the money still have positive extrinsic value at all expirations, but once the strikes are 80 points in the money we start to see some negative values. Let’s zoom in for a closer look:

The further the strike is in the money, the more negative the values are, and the longer they stay negative. However, the situation we want to avoid is to hold from a negative value to a less negative value, so in this example if we sold the 5 DTE version of the 120 ITM strike and held a few days, we lose money. However, if we sold the 10 DTE strike and held until 5 DTE, we’d see decay that would be a profit for this short put.

We can see that the 80 point ITM put bottoms out at 1 DTE, while the 120 point ITM put bottoms out at 5 DTE. The deeper we go in the money the later the bottom point is for negative extrinsic value.

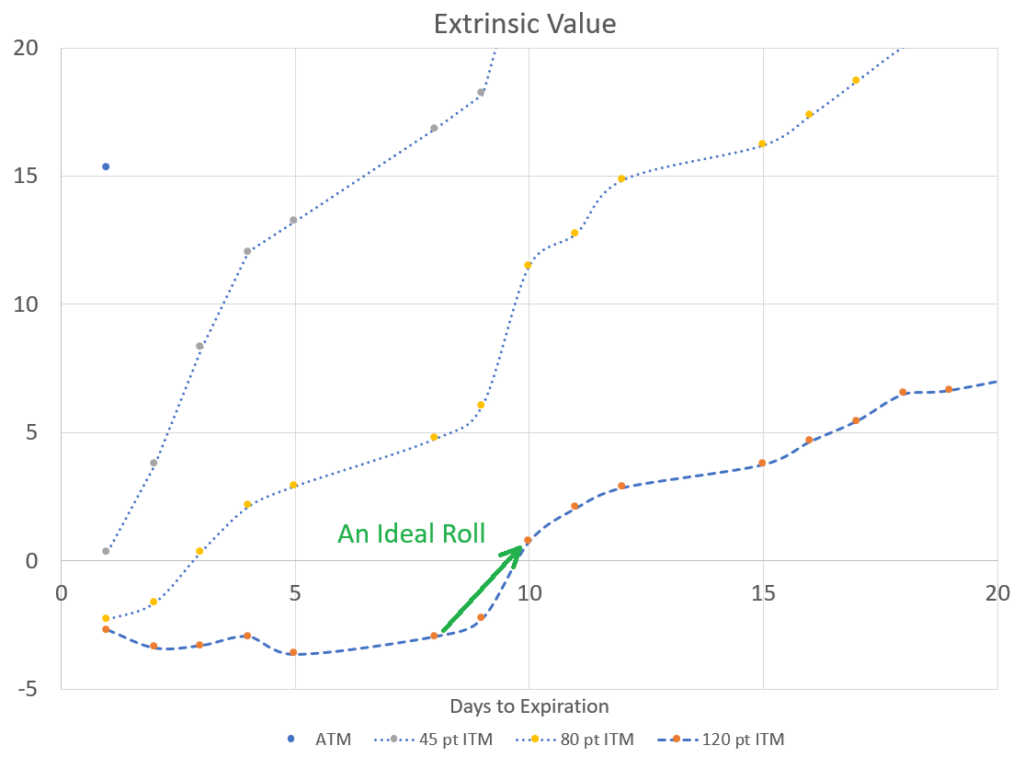

If you are still with me, our plan is going to be to roll our position to the earliest date that we can find our current strike with some positive extrinsic value, no matter how little. Then we will wait for extrinsic value to go negative and then roll back out to a positive extrinsic value. Doing this, we can collect a credit for each roll.

The goal is to roll out in time, collecting premium with each roll and avoiding being in the time frame where the negative values are starting to move toward zero for expiration. At expiration, the extrinsic value has to settle at zero as the option will be settled at its intrinsic value, no matter how negative the extrinsic value was days before expiration.

When the market is down and moving further down, the negative extrinsic value is amplified, and when the market is moving up, the negative extrinsic value is muted somewhat, so the best chance to roll out and collect a premium is finding a time during the trading day when the market is moving up. This makes this activity more of an art than a science.

The goal of each roll is to collect credit and whenever possible move from negative extrinsic value to positive. We want to avoid getting to days earlier than the point where negative values bottom out. Doing this approach may roll the strikes out days or even several weeks in time. If the market stays down, we just lose the opportunity to collect credit on a daily basis. If the market makes a quick recovery, we could end up with strikes that are a long time from expiration that we will have to wait out.

The advantage of rolling for credit is that we never give up any premium that we have collected. Meanwhile, we know that eventually the long end has to close at its intrinsic value and cover the full amount of the downturn. But how much patience does it take to hold on for perhaps weeks or even longer. Assuming the market eventually bounces back, we’ll get all the premium back that we’ve ever collected and hadn’t had a chance to bank. We also don’t have to worry that our strikes will get overtaken by a huge up move from the bottom because our strikes are deep in the money far away from that bottom.

One watchout in this scenario is that the extrinsic value of the long side will be decaying away during this time. On a big enough move, the long extrinsic value will completely disappear. So, while collecting premium on the short side, it may be hard to keep more money than you may lose by eventually needing to roll out the long for more time.

Having traded this trying to collect premium while deep in the money, I can tell you that this isn’t an easy task. One possible help is to get an idea of the roll trade you want to make and enter a limit order for the amount you think is reasonable to collect. Set up the order and go on about your day. If it fills, you win. If it doesn’t fill, re-evaluate your trade assumptions and look for perhaps a later expiration for your next roll.

Maybe this chart will help you visualize what we are trying to do. We want to move from a negative extrinsic value strike to a positive one, then wait for our new strike to turn negative and roll again to a positive one.

How do we know whether our strike is negative? Just look at the difference between the strike price and the current index price and compare to the premium for that strike. Then, when rolling, look to roll to a strike with more premium further out in time.

Example: Let’s say I have a short strike of 6000 at 10 DTE and the market is at 5800. I find my strike is priced at $190, which is $10 less than the intrinsic value of $200, so I have $10 negative extrinsic value. A quick look at other expirations for 6000 strikes, and I see that $190 is the lowest value available, so my premium will likely go up as expiration gets closer, which will lose money since I’m short on this put. It’s lost all the value it can unless the market moves. So, I want to trade for something that has a relatively higher price that can decrease. Looking through my choices I find that the 17 DTE 6000 strike is priced at $201, $11 more than my position. If I roll to that strike, I can collect $11 to stay at the same spot and have decay work for me for the next several days.

You may wonder, if I can collect $11 to roll out a week, should I instead roll down 5 or 10 points to get a credit and get a little closer to the current price? The answer is yes. Let’s say I could sell a 5990 strike at 17 DTE for $193, I’d collect $3 and also get closer to the current price. Win-win if I can find it.

If all this makes you head spin, I understand, it was a lot for me to absorb, going through downturns holding this trade. I followed this second approach of trying to keep collecting credit and ended up rolling out a bit farther than I probably needed to because I didn’t really understand the curves of extrinsic value and I was impatient and just wanted to kick the can down the road.

Which approach is better?

I have some trading buddies that also trade this strategy and we’ve compared notes on how we managed large downturns. Our comparisons could be a little flawed as we all were making up rules on the fly (never a good plan), but the traders that rolled down steadily regardless that they needed to pay a debit seem to have done slightly better than fighting to always get credit, mainly because I rolled much farther out than I probably needed to and the downturn reversed faster than my expirations. A longer downturn may have been better for me compared to my trading piers. So, to me it is just a matter of preference, assuming one knows the pros and cons of the mechanics being selected.

Managing the Long Put of the Diagonal

So far, I’ve only hinted at management of the long put in this 3-60 DTE put diagonal. The long put doesn’t take as much attention as the short put, but there are three key values to keep an eye on and manage. The long put is a balancing act between Delta value, capital requirements, and time left until expiration.

Let’s start with the value that is most obvious that we must manage periodically- time. I’ve opened this trade with 60 days until expiration. At this timeframe, we typically only have two expirations to pick from- the monthly (third Friday) expiration and the end of month expiration. So, in opening the trade I just take whichever is closest to 60 days. When I roll the long put, I roll to the expiration closest to 60 days. I just try to stay consistent.

But when should I roll out in time? I often roll my long put for one of the other reasons and that will trigger me to move out if a new strike is closer to 60 days than my current strike. If the market doesn’t move much and my long strike is at a good Delta and not eating too much capital, I wait until around 6 weeks left or 42 days to roll. I’m trying to avoid the faster decay that comes as we get closer to expiration. When I roll based on time, I also will look to adjust my strike price to the best Delta and capital buying power combination.

With a 40 Delta target, often the trigger that causes me to roll my long strike is the change in buying power required for this trade. As the market goes up, I am likely to be rolling up my short side of the diagonal, which widens the gap between the short and long strike prices. Every 5 points I roll up is essentially another $500 in buying power required. It isn’t completely, because I’m collecting some premium and the value of the long is changing, but for the most part the change in the width of the spread will be very close to the change in buying power. So, I track my buying power with each roll, and set a limit of $12,500. Once I get to above that level of buying power required, I roll up my long, back to around 40 Delta at the closest expiration to 60 days. If I’m already at the closest expiration, I just roll up as much as needed. This will cost me a debit, but my buying power requirements will be reduced in the process as the width of the spread decreases.

Delta adjustments are typically a consideration when I’m rolling down my short put because it has gone deep in the money. At this point my long will also be in the money. If I’m rolling my short put down aggressively every day as I describe in the rolling down strategy above, I will eventually get to a point where my short Delta is less than my long Delta value. For example, maybe my long has a Delta of 65 and I roll my short side down to 60 Delta. I now have set up a bearish Delta at a time where there is a risk of a big upside move. I don’t want to lose money on both the down move and the move back up. So, this would be a good time to roll my long down to a Delta value near the Delta of my short put, perhaps slightly lower. So in this example, I’d look for a strike with a Delta around 60 to match my short. You may choose to pick a strike that makes the overall strategy more bullish, or more bearish, but while I worry about the downside adding to my losses, I know that a break to the upside can lose money that I can’t recover if my short runs out of premium while my long keeps losing.

Backtest Results

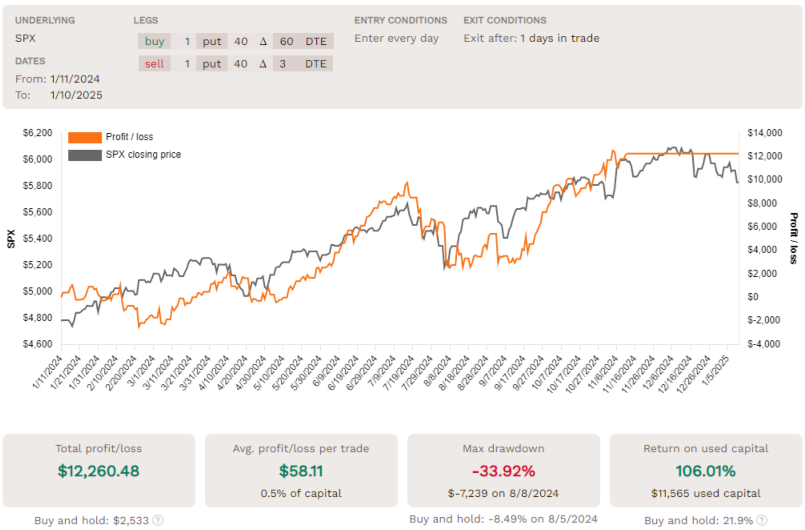

While I only put limited value in backtesting trades like this because rolling strategies can’t really be backtested with software I’m aware of, I thought I’d try to get as much of a test as possible. So, I entered this diagonal strategy into TastyTrade.com‘s free Backtesting software. I entered 40 delta for both the long and short put, and entered 60 DTE for the long put and 3 DTE for the short put. I told the software to open this trade every day and close it after 1 day in the trade. This is the best simulation I can do- essentially rolling to as close to 40 Delta on each side every day. This doesn’t include proactive rolls up, or hanging on to losing strikes on drops in the underlying index. But despite that, or maybe because of that, the results are pretty impressive:

For the calendar year 2024, up until 60 days before the end of the year, the return on used capital was 106%, compared to 22% return on the index itself. I don’t think the backtest software fully accounts for all the buying power that some brokers might require, but it is close. You can see from the chart that returns are quite volatile as the scale is about 5x as wide on a percentage basis as the underlying SPX graph and still ranges outside the index during ups and downs in the market. That matches my experience.

Note that the methodology of the backtest software is to open and close trades at 2:45 Central time or 15 minutes before the close of each trading day. Tasty’s backtest also provides a trade-by-trade log that shows profit and loss for each trade with additional information.

One could argue that the backtest methodology could be a sufficient trading strategy, but my sense from experience is that there are additional gains to be made by being more strategic in rolling as I’ve described. Perhaps the mechanical nature of the backtest points to some advantages that I haven’t recognized. In any case, it’s one additional data point. Remember that backtests are backward looking and don’t guarantee anything about the future, just as my observations of past trades also aren’t necessarily predictive. But as I often point out, some strategies tend to work better than others.

Alternatives- underlyings, different DTE?

Okay, so if you are still with me, you may be asking things like how important is it that this trade be done with SPX? Or can we use a different duration long put, or a different duration short put? Can we use strikes with different Deltas? The short answer is you can do whatever you want, this page is just an explanation of one version of this kind of diagonal trade, a middle of the road variation to show how many factors can come into play. But let’s briefly look at some of these put diagonal alternatives.

Why SPX? What else can be used?

I’ve chosen SPX options for this trade for several reasons. If you aren’t familiar with SPX as the S&P 500 index, check out my explanation about all the different ways to trade the S&P 500 index. Options on SPX are extremely liquid, have expirations every day, are cash settled, can’t be exercised early, and have relatively low commissions and fees as a percentage of the value of the options being traded. Additionally, the S&P 500 in general is very diversified as an index and has relatively low volatility compared to almost every alternative, with less outsized moves than almost any other underlying.

There are two other indexes that currently have expirations every day, the Nasdaq 100, or NDX, and the Russel 2000, or RUT. There are micro versions of those indexes with daily expirations, but they don’t have a lot of volume and can be very hard to get out of positions at good prices. If daily rolling is what you want to do, these three are probably the best. There are also Futures options on all these indexes. They can be used with a little less capital, using SPAN margin, and can be traded almost around the clock. You pay more for commissions, and liquidity is less in off market hours.

We can do diagonals with virtually any underlying, stocks, ETFs, you name it. But, most currently can only use weekly expirations at most, so no daily rolls. That’s less stress and less trades, so maybe it is a benefit to you.

Individual stocks have higher IV, so more decay to work with. If you can deal with occasional crazy moves, a diagonal on a stock can be very lucrative. I have some trading friends that make this the majority of their trades and do very well.

Is there something magic about 60 days?

In a short answer, no, there’s nothing special about 60 days. I was looking for a significantly longer duration for my short put than my long so that decay was much greater in my short put.

One could argue that shorter duration has less risk with lower premium cost. So, you could go with less time, trading greater decay for a little better capital efficiency. However, the shorter the duration of the long put, the more often it will need to be managed to stay close to the target duration you want.

Shorter duration options have more Theta (decay) and more Gamma, meaning the Delta tends to change more over time with price movement in the underlying security. Longer duration puts can maintain almost constant Delta over a longer period of time and price movement.

So, yes, you can trade different durations. As I’ve mentioned, I’ve already written another write up with a similar trade, but one that has 5 years duration on the long side.

1, 2, 3, 4 DTE? A few weeks?

Is there magic to the length of the short put in a diagonal? As we’ve already discussed, the shorter the duration, the greater the decay or Theta, but the lower the premium is, so the closer the monitoring of the position needs to be. Selling a 1 DTE and rolling back out each day on expiration day before expiration actually gives the best return on the short side. The challenge is that this means the trader has to deal with this every day, and maybe multiple times in a day and always be alert to not have the market run away to the up side. With lower total capital involved, Pattern Day Trading can easily be triggered, knocking out trading in accounts with less than $25,000.

With each day extra of duration, you get a little less decay per day, but a little less urgency to manage the trade as closely. And if you are trading a diagonal on a stock or ETF that only has weekly options, you can only trade options that are 7 days apart and you don’t worry so much about each day’s decay, just the watchout to make sure that there is always premium available to decay.

You can change the number of days the short is out in time for a number of reasons. Say you go on vacation or you have a day you know you can’t trade. Just roll out the short side as many days as you need to be away for a bunch of extra premium and hope things stay reasonable while you are away. Or, as we’ve discussed, if you want to collect a credit when the short put goes way in the money, you may have to roll out several days, or even weeks, to keep collecting credit.

The bottom line is that each trader can choose the duration that works best for them, just understand what the implications are of that decision.

Why Delta matters

Here’s maybe the most important point of trading diagonals- the Delta of each side matters more than almost any other factor in setting up and managing the trade. The Delta values of the strikes you pick determine whether the trade is bullish, bearish, or neutral, and by how much. The examples I’ve shown in this write-up have tended to have both sides of the trade with 40 Delta in each direction, making this a mostly neutral trade. You can see that I’ve tended to tweak it slightly to the bullish side, the short has more delta than the long. This is because there is more of a penalty to the upside, in that the lost decay from the short can’t be recovered, than there is on the downside where you can roll and wait to get your lost premium back.

Where I’ve seen people really underperform on this trade is when they’ve looked at the low or even negative extrinsic value of deep in the money long puts, puts with 60 Delta or higher. Couple this with a short Delta of 20 or less because the same person wants to avoid having their short get in the money, and you have a very bearish trade that does badly in any kind of uptrend, which is the majority of the time. If you are setting up for a bear market, maybe this will work, but most people I’ve seen do this set up do it without understanding how powerful the impact of Delta is on the performance of the diagonal.

So, this brings up another way that a trader can modify the trade to match their outlook. By intentionally adjusting the Delta values, you can make this setup either bullish or bearish by picking strikes at different levels on either the short or long side. I tend to not try to predict the future, so I’m more inclined to be close to neutral, with perhaps a very slight bullish setup, but to each their own.

If -40/+40 Deltas work, how about -50/+50, -60/+60, or other semi-neutral combos? Sure, I see a lot of people trade these types of strikes, especially if the long put isn’t a very long duration. Maybe someone is trading a diagonal with 1 week on the short end and one month on the long end, so they pick both strikes at the money with about 50 Delta on each put, which if the strikes are the same, it is no longer diagonal, but a calendar trade. On our longer setup on the long side, higher Deltas mean the position will be in the money more often on the short side, which can be manageable as we’ve discussed. There can be more premium to decay at higher Deltas as well.

An advantage to working with higher Deltas is that we can avoid the double risk issue that we have in the setup I’ve described with this trade setup. If we move to -50/+50 or -60/+60 Deltas on this trade, our long strike can be easily set to a high strike price than the short put, so our risk is only the difference between premiums. Higher long Delta also makes a better hedge for the long fight with down moves. So, several reasons to consider, especially as duration of the long put gets shorter in time.

As you plan how you want to set up a trade like this, pay attention to the Delta values as well as buying power requirements for the strikes you end up with. There are lots of combinations that work, but if you ignore Delta, you can end up with some really poor trades that just lose. I’ve known a number of people that ignore this and can’t figure out why this kind of trade rarely works for them, and they just don’t get it.

I’ve done more backtests and found interesting results. See my post on Backtest to Optimize Strikes and Delta of a Diagonal Put Spread.

What kind of results can this deliver?

My experience with this specific version of diagonal is that I tend to average around a 3-4% gain per week, taking into account the net profit of both sides of the trade compared to the capital required.

I think it is important to pay attention to the performance of both the short and long side of this trade. In most cases, the short will make money while the long loses. If you only watch one side or the other, you can get a very skewed view of how the trade is performing. One trader that I know that was doing a version of this was very proud of how much premium he was making on the short side, but couldn’t understand why his account wasn’t going up. He was trading fairly low Delta shorts that he could roll every day and they were nearly worthless when he rolled, so it looked great. But, on days when the market went up, his longs were losing more money than his shorts were making because he wasn’t aggressively rolling up his shorts when the market went up. He missed that part of the management of the trade and his results showed it. I’m a proponent of logging all trades for ongoing analysis, and I think it is especially true with this type of trade. If you see that the trade isn’t making money when it seems like it should be, it is a prompt to go look at the mechanics of how you are managing the trade day by day, and look at how each side is contributing to the result.

There is a higher amount of volatility on a day to day basis on a percentage basis with less duration on the long side. What I’ve seen trading this at different durations is that the gain on both the short and long side is nearly the same with each variation, assuming that the Delta is mostly neutral. While the average gains can be very good, the flip side is that losing days/weeks can be much larger and you have to expect big percentage profit moves day to day. It’s not uncommon to show a loss of several thousand dollars in a day, so if that is troubling to you, this may be more volatile than you can manage. Pros and cons for every decision.

When the market is down for extended periods, this trade will not make money. As a result, it is fair to assume that the average of good and bad periods will be lower, perhaps at the 2% rate shown in the backtest, or even lower.

Final Thoughts

This is by far the most complicated trade to explain that I have taken on in options. There are a lot of layers of detail that aren’t immediately apparent at first glance. I’ve tried to present the good, the bad and the ugly of this.

As an update, based on the way this has traded, I did some additional backtesting on this trade vs other variations, and the results are in this linked post.

In the end, the appeal of this trade to me is that it allows me to simulate being free to sell naked puts at short duration without the true consequences of actually selling naked. This is also a trade that continuously rolls a short option (my favorite way to manage a trade), with protection on the downside, which you can’t get in other trades. Everything else is just a lot of details to enable this. Those many details are all the crazy peculiarities of option trading, kind of summarized like you don’t see in many other option strategies, so it is a great learning opportunity. So for all those reasons, I hope you can understand why I felt compelled to write this and in so much detail. Happy trading!

This was a good read, thanks for putting it together.

Question 1: have you backtested this to see which performs better (selling 60 delta, selling 50 delta, selling 40 delta)? Or mix and matching the delta (selling the 50 but go long on the 60, for instance)? Curious what an ‘optimal’ approach is.

Question 2: how did this look in the first half of 2025, when Trump tariffs took the market down basically through March, but then pushing off the tariffs lead to sharp rebound April onwards? Thanks.

1. I’ve done quite a bit of back-testing and here’s one post on the topic. I haven’t tested everything, but I tend to like selling 50-60 Delta puts and buying 35-45 Delta puts in this type of trade. I don’t want my strikes to get too far apart, because in a big move down, I want the potential to roll way out and not lock in too big of a loss.

2. If someone was able to hold the short position, the bounce back would have erased all the paper losses. However, most brokers won’t let you have a short put over 5% in the money hedged by a longer dated put. You might be able to add a put at the same expiration if you had enough capital to cover the spread risk and keep it alive and wait for a recovery. Otherwise, you’d have to roll down and take the loss, or close out completely for a bigger loss. This is the downside of this trade- it does extremely bad in bear market moves.

Hey Carl, This is one of the trades i do regularly and I loved reading your excellent post about it. i marvel at how you are able to write and explain it all. i have a couple of differences though and i would like your opinion, if you dont mind. i usually keep the short put 2 dte at 50 delta (to max extrinsic decay), and long at 30 dte, but at about 25- 30 delta, to allow for the positive drift of markets. Which obviously means that i get burned on downmoves (like last week). May I ask:

1) I read somewhere you favor positive drift. what has been your experience between delta neutral and small bullish tilt trades?

2) Did you change your long put to 10DTE (per your other post) or running some other DTE on the long

3) WHen you enter a 3 DTE short, why not take it expiry? is it to avoid gamma and smoothen the theta?

4) After a deep correction, i am often forced to roll out in time for lesser debit/some credit (like you mentioned too). i keep delta high to take advantage of a recovery. What do you do if market recovers the next day? oftentimes, the Pnl wont be made back because the gamma on the new, longer DTE isnt that large. how do you handle such recoveries?

If it’s any help to you/other readers, happy to contribute my experiences/lessons. Thats what this site feels about

Excellent questions- you are asking about the most important and difficult decisions that are required for this trade. Let’s take them in the order you asked.

1. Having positive Delta is great when the market is going up, which it does more often than not. You get outsized gains, and generally avoid losses from very large up days. However, the flip side is that this means bigger losses on big down days. Given that this kind of trade is extremely volatile already, adding volatility with unbalanced Delta doesn’t really seem prudent, so I stay very close to neutral, with perhaps a slight positive slant, but I don’t know that I can say that is preferrable, more just a personal preference.

2. I have tried the 10 DTE long and it has been helpful in reducing swings. Good days aren’t as good, but bad days aren’t as bad. The only downside I see is that I need to be on top of the trade and be ready to adjust more quickly when the market is moving a lot. I say that because I also have reduced the duration of the short put at the same time.

3. I just don’t like the drama of expiration and if a position is well out of the money, I don’t see the benefit of keeping it on where it could end up back in the money later. So, yes, I want smoother Theta and Gamma.

4. I’ve experienced exactly what you are describing. When the market recovers quickly, and my short strikes are longer than my strategy normally calls for, it just means than I gave up several days of gains that I could have had if my duration was shorter. But, by not capitulating at the bottom, I didn’t lock in losses, so I probably will come out ahead compared to that. Sometimes you have to accept that you aren’t going to always make the right decision and second-guessing is human nature. I take those situations and use them to re-evaluate my mechanics- what will I do next time? What criteria will I use?

I’m very hesitant to say much more about this trade. I’m still studying and looking for ways to reduce the incredible variation that it produces. While I’ve made more than I’ve lost, it has been extremely risky and volatile results. There is no other trade with more ups and downs that I have traded extensively than this one.

Hi Clive

Thanks for very the reply above and helpful to hear your opinion.

1. Is this strategy one of your core strategy and which others do you trade on regular basis?

2. You have mentioned above that you have shortened the short put DTE; are you trading short put at 2 DTE and long at 60 DTE?

At the time of this writing, this is one of my core strategies, although I keep it small due to the volatile nature of its returns.

Yes, I trade the short at 2 DTE, and lately I’ve reduced the long to 28 DTE. I’m still studying and testing this strategy to try to reduce the maximum drawdown, which can be severe.

HI Carl, hope been keeping well.

Now you and I are trading exactly the same deets. 2/28 :). Maybe I can get some thoughts from you and share mine as well?

1) AT my end, i dont mandatorily roll daily. if market hasnt made a large move (defined by delta explosion either direction), I let it go to expiry day to harvest the theta/extrinsic. If large move, i try to realign deltas as much as possible. Also I will draw in the long after a large move lower to reduce my pain, and thats why like to start out with some decent DTE on the long. Do you roll daily? What guides your decision? Do you shorten long’s DTE to offset loss from the short leg? any other strategy?

2) I close the long at about 8-10 DTE, when I feel its damping returns too much. How about you?

3) Lastly, you mentioned you prefer delta neutral (mild positive), but a short DTE short put’s gamma will often make you look long delta (hope that made sense). So do you have any rule for staying out of market, lets say when its bearish? i am fiddling with using some ema crossover (not because i like MAs, but to provide a framework. They are as useful/useless as any other indicator)

Cheers

Thanks for the thoughtful commentary. I’ve tried trading this type of strategy so many ways and I haven’t landed on one set of mechanics that feels really right. While my backtests pointed to two day shorts, I don’t like how easily an upmove can make the short worthless, and how closely I need to watch. So, I find myself rolling out at times to longer durations for my short side, up to 7 days. I still get decent decay day to day, but without as much Gamma. I’m giving up some Theta, so my positive days are less profitable, but my negative days are lower losses.

Whatever my short, I generally roll every day, although when my shorts are a week out, there isn’t any pressure to do so, so if I get busy, it isn’t critical. For my longs, I roll a few times a week, trying to keep my long put between 21 and 28 DTE. Again, I don’t stress about it, but if I’m going to move my short up or down, I usually move my long about the same amount. I’m finding this less rigorous trading plan a lot less stressful, but then the last month or so has been strong with the market trading in a somewhat narrow range, so there shouldn’t be any stress.

I’ve also reduced my total number of positions with this strategy as I just don’t feel like this is something I want large exposure to the next time the market drops 20% or more. I guess I’m starting to have some inclination to be at least a little risk averse.

Hi Carl,

Just found your website and diving into all the great reading. So far have read your rolling put credit spread and now this article. Seems like the rolling put credit spread is a little simpler and maybe less drawdown. With basically the same idea of taking advantages of markets staying neutral or drifting up. Is the rolling put credit spread your bread and butter for options?

Yes, rolling credit spreads is probably my favorite option strategy and the one I find easiest to manage.