Covered calls have a number of trading advantages- they reduce volatility, provide some income, somewhat cushion a position from a fall. But, to have a covered call, you have to own stock first to sell a call against it. However, we have discussed the idea of using long calls as a substitute for stock, so if we sell a call against our stock equivalent we can have a low cost equivalent of a covered call, in other words a Poor Man’s Covered Call.

One difference is that our long calls have decay, and we want to counter that decay by selling calls with the same or more decay in our favor. A great way is to create a diagonal spread, selling calls that are closer to expiration while buying calls that are further away.

By selling a call with faster decay against our long call with slower decay, we can actually get a trade that has a greater than 50% probability of profit. The trade-off is that we limit the upside. The trade has defined risk and defined maximum profit.

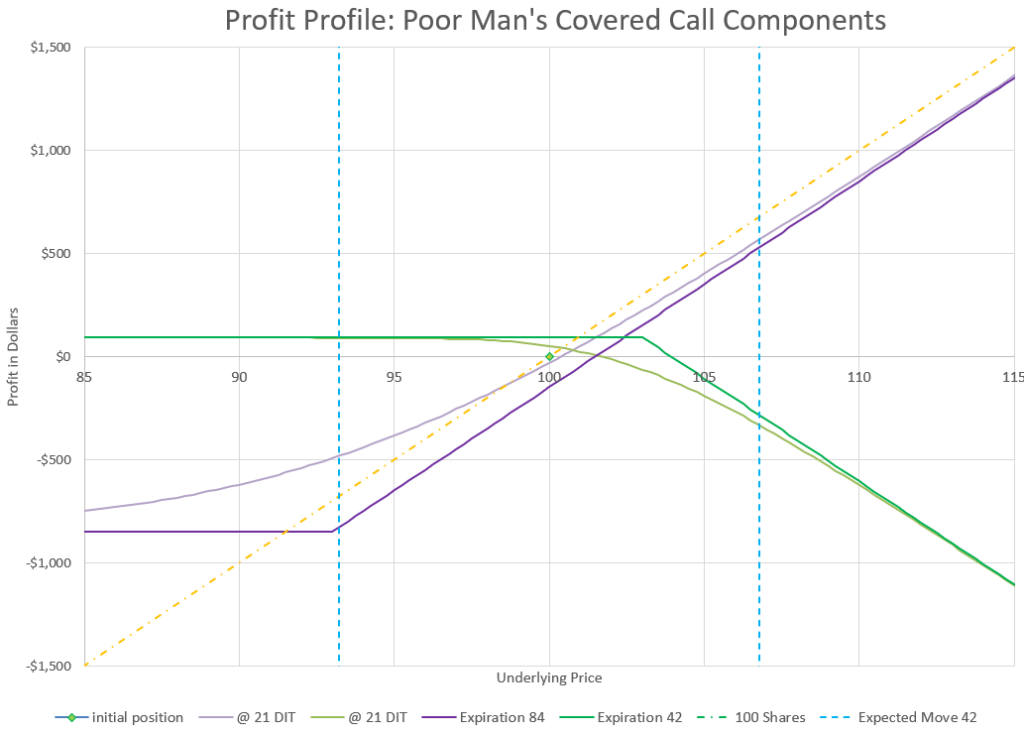

My typical setup is to buy a 75 Delta call about 12 weeks out and sell a 25 Delta call about 6 weeks out, or half the time. If we look at a chart of each of the options profit potential along with how they compare to just owning stock, we get a bit of a complex chart:

The key thing when looking at diagonal spread positions is that we really can’t think that much about expiration, especially for the long duration portion of the trade because it expires later. So, we really have to pay attention to how the projected values will behave at different points in time prior to expiration.

Another thing to notice is that the short call we sold has a strike price much closer to the current price than the long duration call. This means that there is more potential downside than upside, but that’s true with a regular covered call as well, actually even more so. At least our downside on this trade is limited.

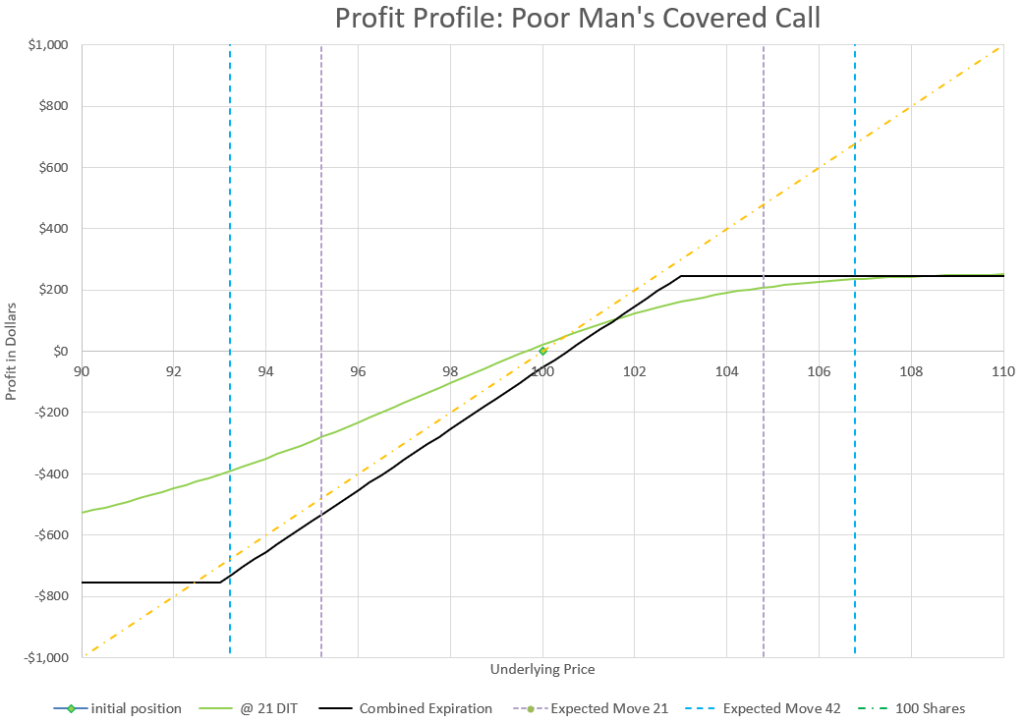

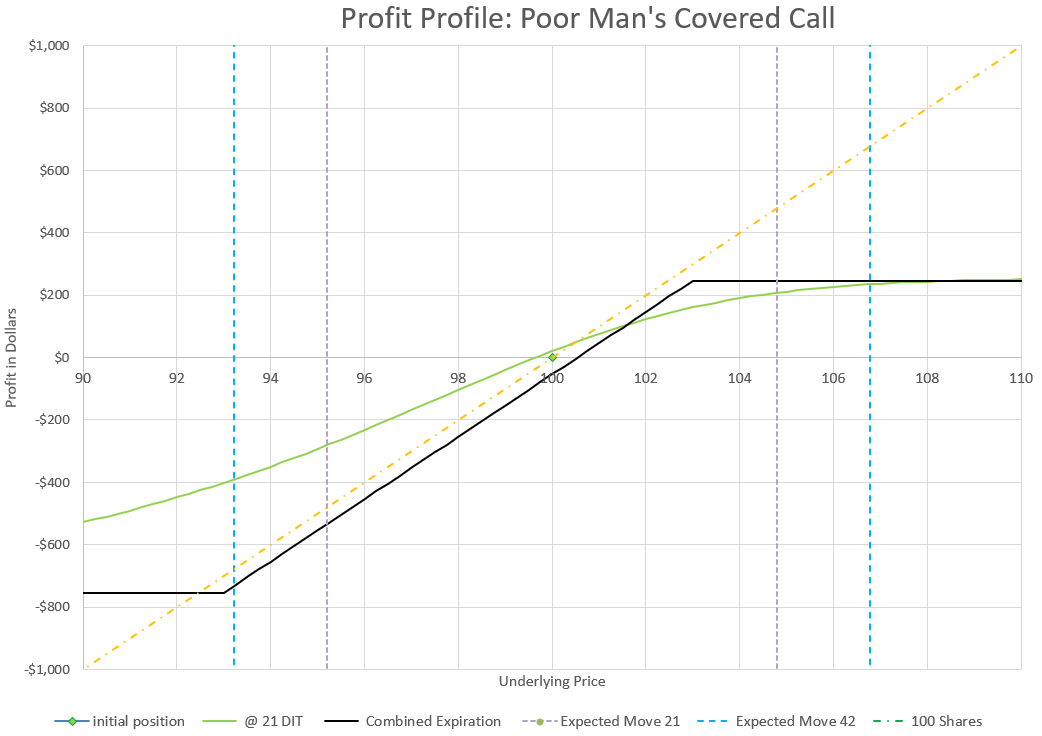

When we put it all together in a chart, we can see how the trade profits not only when the market is up, but when the market is flat as well. Profitability with no underlying price change is due to the faster decay of the shorter duration short calls.

Looking at the overall Delta of this trade, it opens with a net Delta of 50, or the equivalent movement of 50 shares of stock. So this position is half as volatile as owning 100 shares of stock for a cost equivalent to about 7.5% of owning 100 shares.

From a profit standpoint, our capital required was $750 and the maximum profit is $250. This shows how much upside we’ve given up by selling the call, compared to unlimited upside with the call alone. However, if we look at a “sweet spot” on the profit chart above, we can see that if price goes up from 100 to 102 in 21 days, the profit is around $150, a 20% return on capital for a 2% move. In comparison, a 2% price move on the earlier long call option only would yield about a 7% return on capital, and owning stock outright would net the owner, well, obviously 2%.

Managing the Poor Man’s Covered Call

How do we manage a Poor Man’s Covered Call? Generally, there are three ways to manage positions like this: hold, fold, or roll. Let’s take them one by one.

Hold means we just hold until expiration. But, remember these options expire at different times, so we could hold until the short leg expires and close the long. We’ll get good Theta decay and not really need to pay much attention. Probability of profit is over 50%, so it’s a viable strategy. However, if we let both options expire independently, we can see from the expiration profit chart that we need an increase in price to be profitable, so we do need to get out of the long call before expiration, preferably when we exit the short call.

Folding or getting out with an early exit isn’t a bad choice either. We can set a profit target, say half the maximum profit and set a limit order and also have an equal stop loss or slightly larger stop loss, and let the trade play out. Probability is over 50%, so hopefully we catch a modest up move and miss any big down move, collect a nice profit, and move on. As a short term strategy, this can be a good approach, especially if we were to set up a ladder of ongoing versions of this every few weeks and just let each one play out individually.

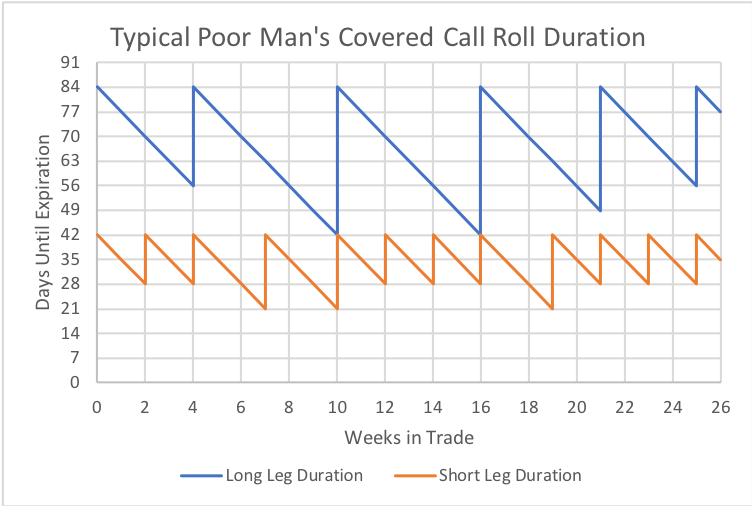

If you’ve read much of the other parts of this site, you know that I tend to favor rolling strategies, often continuous rolls. I like to roll positions out in time, over and over, adjusting them up or down with the market. Generally, the plan for this trade is to actively manage the short duration leg more than the long duration leg, but keep the long duration out in time and the short duration around half the time as the long, give or take a bit.

In the chart above, I’m illustrating the concept. The idea is that every two to three weeks the short leg gets rolled out in time. Well, which one is it, you might ask, two or three? I would look at it based on criteria, if the short has gotten way out of the money, say below a 12 Delta in two weeks, I’d roll out and establish a new 42 day position and collect a net credit. Or, if the short strike is being tested and has moved to a Delta of 40 or more, I’d roll out and try to reduce Delta and collect a credit in the process- it’s easier to roll a single short leg for a credit than to roll a spread, so I should be able to improve my position in the process. If however, the price keeps Delta between 12 and 40, let’s just keep collecting Theta and wait until 21 days left to roll. At that point, we roll out to 42 days again and pick a nice strike and get a nice credit for our effort.

For the long call, I mostly just leave it alone. I let it do its thing until it gets down around 42 days and kick it back out to 84 days. If the market is up, I can move the strikes up to 75 Delta and get a credit. If the market is down, I’ll have to pay to roll out. If there is a really big move one way or the other, I can roll out at the same time I’m repositioning the short leg.

Managing Big Moves

So, we can set up rules to guide our rolls and generally just let the data from the market dictate our actions. The only other thing to consider is what to do if the price jumps way outside our strikes? With individual stocks, this is a clear possibility, so there needs to be a plan. On a huge jump up, the choices are to close for a max profit and move on figuring that all the good news is priced in, or reset with a roll to new strikes in anticipation of further up moves. On a huge down move, we can close out both sides for whatever premium is left on the long call if it looks like the bottom has fallen out for good, or just hang on to the long call and hope for a reversal, maybe selling a new call at the same price to cushion the blow. There’s no right answer, just the right answer for each trader’s personal tolerance for risk. But, every trader needs a plan. The one strategy that many traders take by default is to cash in small gains and hang on to big losers, which pretty much guarantees a losing portfolio over time.

Overall considerations

Is there any magic to 84 and 42 days? Not really, it’s just a time frame that I find fairly manageable without a lot of stress, but with plenty of premium to collect on the short side of the trade. Longer durations have less stress, and shorter durations are more volatile with more potential profit. It’s a choice that depends on your trading preferences and risk tolerance. Many traders of this strategy like to go to much longer durations with their long strike, to six months or even a year, to keep Theta less, but the trade-off is that the cost and downside risk is more.

Similarly, is there magic to 75 and 25 Delta? Not magic, but the goal is to have more decay in the short strike than the long, so equally distant Deltas at different expirations should achieve that. Many traders will buy call strikes deeper in the money to make this advantage greater, with the trade-off of a higher premium cost and having more more capital.

Between time to expiration and the Deltas chosen, we can significantly adjust Theta of our long strike. We can also greatly control the amount of capital required for the long call, from around 5% of the cost of stock to 20%. Understand that this is the trade-off, capital cost and downside risk vs. decay. The ultimate extreme is going back to a covered call, where we own stock instead of a call. Buying a call instead saves capital, and also limits the loss. So, in choosing the long side of the strategy, consider the choice of time and Delta as part of a continuum of risk and reward.

Trade Sizing: Leverage and Risk

Finally, remember that just because a poor man’s covered call has less capital required than a standard covered call, it doesn’t mean that it is a good idea to do 10 poor man’s covered call positions instead of a single covered call. Just because a trade is affordable, it doesn’t mean it is a good idea to bet the farm on it. The poor man’s covered call is a trade of leverage. It can be a trade to reduce volatility or greatly enhance volatility.

Let’s look at our example trade on $100 underlying stock on a $10,000 account. We could buy 100 shares of stock for $10,000 as a base case and use all our capital and we have market risk all the way to zero with a Delta value of 100.

If we set up one contract of the poor man’s covered call like our above example, we risk $750 and have the equivalent of 50 shares of stock, so much less volatility and downside risk, while still controlling a notional 100 shares through our contracts. Our loss is limited to $750, which will occur if we hold our long to expiration with a stock price change of more than 7%. This becomes a very conservative trade compared to owning stock or a traditional covered call, if we keep the rest of the account in cash.

If we trade two contracts, we have 100 Delta in total portfolio for a cost of $1500. At this point, our volatility is the same as 100 shares at the current price. However, our loss is limited to $1500, not $10,000 like stock. But now, we lose 15% of the account value on a 7% down move as we are controlling 200 shares of notional value through 2 contracts. We also get double the benefit to the upside compared to one contract. We also get double the Theta of a covered call, or a single contract of a Poor Man’s Covered Call. So the trade acts like stock when the price stays close to the opening price, but shows some leverage on moderate price moves. Arguably, one could say the extra benefits of leverage are worth the potential added risk to the downside- we still are only risking 15% of the account value, not all of it.

What if we take the trade to an extreme? We can easily do 10 Poor Man’s Covered Call contracts for $7500 cost. Our Delta increases to 500, so we get 5 times the movement of owning 100 shares, and our ten contracts now control 1000 shares of stock, a notional value of $100,000! With all this leverage, we get huge Theta. We also get a lot of volatility. If the stock goes up 1%, we make 5%, but the downside is the opposite. The big risk is that we can now lose 3/4 of our account if the stock goes down just 7%. Now we’ve made this trade into a virtual roulette wheel, big wins or big losses. Our probability of profit is still over 50%, but we’ve taken on a huge risk. Our max loss is a move down of just one standard deviation, which is not that unlikely. In fact, if we trade like this for very long, we will surely hit max loss within a small number of trades. We can potentially limit worst case scenarios by cashing out when the going gets tough, but that goes against natural instinct and can be hard to follow as a plan. The bottom line is that this would be a clear example of way too much leverage.

The point of these capital use examples is to show that a trader has to really understand the advantages and risks of leverage in a trade like this. The same trade can be very conservative, or extremely risky, depending on the context of the account it is in. So it is up to each trader to evaluate how the combination of trades affects the performance of the full account. You can read more about these concepts in my write up on Portfolio Management.

Assignment Risk

Since the Poor Man’s Covered Call involves selling calls, there is always the potential for those calls to be exercised by the buyer. With an actual Covered Call, the exercise means the covered shares are sold to fulfill the contract. But with a Poor Man’s Covered Call, there are no covered shares, just a long call in the money. Assignment in this trade means that the account has to sell shares that aren’t in the account, so the account holder will end up with short shares plus cash from their sale.

From our example we have been using, let’s say that the stock goes up to $105 and the short call of our position gets exercised by the owner of the call. We wake up the next day with -100 shares of stock and $10,300 added to our account. And we still have our long call contract well in the money. It’s a mess. A lot bigger mess than just having our long stock sold, because there are more moving parts. But it’s a good mess, because our positions have made a nice gain, especially our long call.

We can untangle our mess by buying our short shares back. We can also sell our long call at the same time to get a clean slate and then decide whether we want to open new positions at Deltas that are closer to where we’d like to be. So it isn’t that hard to straighten everything out.

In my write-up on Covered Calls, I wrote a long section on how to avoid assignment. The discussion is the same for this trade, so I won’t repeat it. Read the Covered Call write-up if you want to explore those tactics. There’s really less concerns about assignment with a Poor Man’s Covered Call because eventually the long call needs to be sold or rolled and the combination of the two can be re-positioned together if needed.

Final Thoughts

The Poor Man’s Covered Call has a lot of advantages compared to owning stock and selling calls. The trade provides a bullish outlook with positive Theta decay, while limiting risk to the downside. It typically has a greater than 50% probability of profit, while being a debit trade, which is rare in options trading. The trade does provide leverage, so care must be taken in managing the size of the position within any account.

Quick introduction : as most comments left, I do like what you write! Clear, elevating me by asking the good questions and not only giving ‘recipes’. Really well done.

Now, I’d love to get your opinion on a strategy I am considering : a Not So Poor Man Covered Call. I’ve been doing for three months with quite good success but mostly because markets are bullish.

Concept : buy a very very long horizon SPX call (Dec ’29) instead of SPY and rolling a covered call on a twice a week basis (Wednesday then Friday the Wednesday again). I get a decent 150% return on margin, probably 70-80% on planned capital, I have not done the math yet.

Thing is : I also plan to get a long term bonus on SPX climbing the ladder.

The special thing is the horizon : Dec 29. As I believe in a non improbable chance of a severe crash in 2025, taking a long horizon gives me the stability to recover (though researching tells me market may not recover in 5 years). My enemy will be time decay as the extrinsic value of the Dec ’29 call is quite high.

Math are for instance :

SPX (underlying) : 6050 today

Strike : 5500

Premium : 1832

Delta : .80

Extrinsic value : 1282

Leverage : +1% of underlying = 2.6% of price call

With these numbers, I need SPX to grow by 5% per year (exactly 320 points) to match the decay on average.

What do you think of this strategy VS a rolling strategy of 6-month SPX call?

Stephane- Thanks for the kind words. Clearly, the further out you go in time, the less decay you have per day/week/month. The challenge I’ve always found is that the short calls are prone to get over-run over time by the long calls as the market goes up. However, that then makes the trade very non-volatile when both options are in the money, so maybe not all bad.

It’s interesting that you chose this strategy. I’ve just finished up an extensive write-up on essentially a counter trade to this, a very long and very short diagonal put, or poor man’s covered put that I have traded, using a long put 5 years out in time. One advantage of deep in the money puts at long duration is that they little extrinsic value, and in many cases negative extrinsic value, but that’s because everyone expects the market to go up, along with several other reasons.