While many might not consider ratio spreads to be a basic strategy, they are often used in a variety of ways to take advantage of differences in decay characteristics, or differences in delta, or differences in extrinsic/time value. These differences cause these strategies to have unique ways of behaving during the time between opening a trade and expiration. This adds an extra dimension to option trading, which takes a lot of analysis to grasp.

In this category, I’ll discuss four kinds of ratios- front ratios, back ratios, broken wing butterflies, and broken wing condors. In each type, there are countless ways to set up trades to capture premium or gains. Many of these trades can be entered by collecting a credit and exited with an additional credit if the trade goes particularly well. In other words, a trader can make money on both ends of a trade- a hard concept to even grasp.

These trades can vary dramatically in risk. Front ratios have undefined risk, but can be modified with an extra broken wing into butterflies or condors that have defined risk. Back ratios also have defined risk. As with all trades but particularly with these ratio type trades, it is critical to understand the potential risk, the possible reward, the probabilities of various outcomes, and have a trade management strategy at the outset.

The Front Ratio Spread

The front ratio spread, or ratio spread as it is normally called is what most people think of when discussing ratio spreads. If you look to the internet for ratio spread strategies, most of what you’ll find is various forms of front ratio spreads. Typically, the idea is to buy one option at or just out of the money, and sell two options further out of the money that cost a little more than half the cost of the option that was purchased. This can be done with either puts or calls, but skew helps make the short puts have more Implied Volatility than the long put, so pricing is more to the advantage in selling put ratio spreads. This trade can win two ways. First, the price moves away from all the strikes and the whole position expires worthless and the trader keeps the initial premium collected. Second, the price may move between the strikes, so that the long option is in the money and the short options are out of the money. The trader can then sell the long option for a credit or take assignment, a win on both ends of the trade. However, the dark side of the trade is if the price moves beyond the short strikes- there is no limit to the loss because the risk is undefined with two short options and one long option. Generally, this is a high probability winning trade, but a loss could be devastating in the somewhat unlikely event that the market moves way beyond the short strikes into the money. If a trader is fully trading all of an account on margin and this happens, the account will be wiped out. One solution is to buy an additional wing, creating a butterfly or condor which we will discuss next.

The Broken Wing Butterfly

What sick person comes up with these names, my wife often asks me? I don’t know, but it comes back to a graph of profit vs price at expiration. A standard Butterfly has a thin body of profit and long wings of small loss on either side. In most cases a broken wing butterfly has a thin body of profit, but one wing of profit, and one wing of loss. The broken wing butterfly can be done with puts or calls. I was first exposed to this strategy by Mike Butler and Nick Batista of TastyTrade.com, who for a time promoted this trade almost daily on their show.

The setup of a broken wing butterfly is sell two options at the same strike, usually out of the money, and buy one option closer to the money or even in the money, and sell another option twice or three times as far away on the opposite side, well out of the money. Ideally, the transaction creates a credit to open, as the two options being sold are more expensive than the total of the two options being bought.

There are a couple of ways to think about this trade theoretically that may help in understanding. One is to consider this as two spreads, a debit spread close to the money and credit spread further away from the money, and the credit spread is initially worth more than the debit spread, but will likely decay faster as it is wider and further out of the money. Another way is to think of this trade as front ratio spread with a far out of the money option bought to define the risk. Either description is accurate.

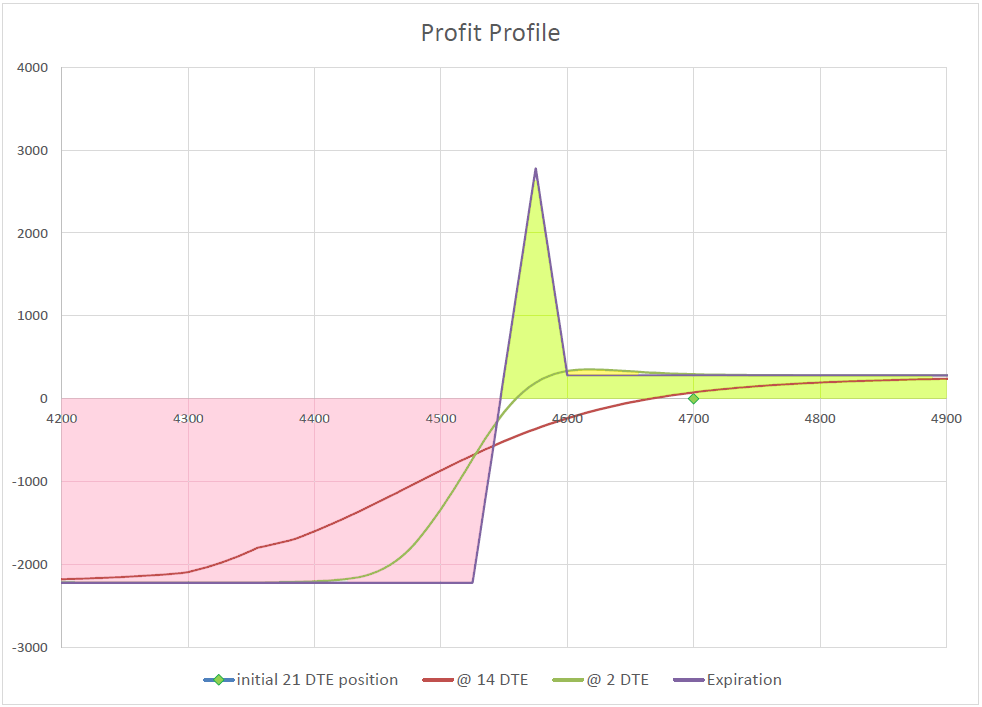

Like the front ratio spread, this trade has two ways to win. Most likely, all the strikes expire worthless out of the money, and the trader keeps the premium. There is also a peak value of profit that occurs if the price ends up near the short strikes. If price blows through all the strikes, max loss is the difference in the width of the two wings.

I’ve seen traders use the broken wing butterfly in a number of ways. I personally like to try to get as much credit as I can, watch the premium collapse and get out. Others try to position the body of the butterfly where they expect the price to move to at expiration to get a big win.

To capture the maximum profit, the trader opening this trade needs the price to end up exactly on the short strike at expiration, which is highly unlikely. However, if the price ends up close to the short strike, the payoff can be big. The big payoff only happens at expiration, or in the last hours of expiration day, so shooting for anything close to max profit can be very nerve-wracking. If price moves a little too far past the maximum profit zone, the trade can end up at maximum loss.

One management strategy that tries to get the best of both winning strategies is to roll the strike of the broken wider wing to the same width as the narrower wing. This can often be done after premium has decayed significantly, and the cost to roll the wide strike is minimal. Doing this roll takes off all risk and locks in a profit of the difference between the premium originally collected and the debit paid to roll the wide wing. What is then left is a “free butterfly” that could potentially pay off big if price moves in between the long strikes at expiration. However, this isn’t likely, because to be able to roll for a small debit, the price has to be way out of the money. The price would then need to reverse significantly in a short period of time. It is possible, but very low probability.

I’ve written a post about my favorite way to set up this trade as a 21 day Broken Wing Put Butterfly, and also a note about how I made 500% in a year with this trade.

The Broken Wing Condor

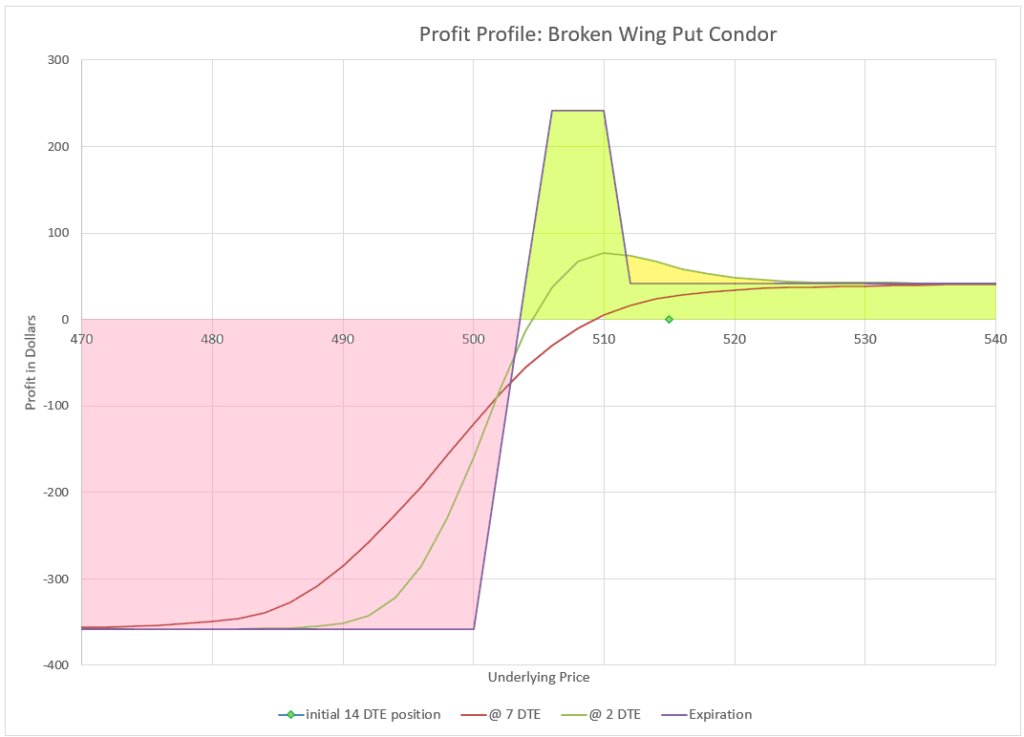

One issue with the broken wing butterfly is that the area of max profit is very narrow, and a slight miss moves the trade to max loss. But what if we could widen the area of max profit, but generally keep the other positive characteristics of the broken wing butterfly? We can, with a broken wing condor. Nick and Mike at TastyTrade also introduced my to this trade, although they like to call it a “broken heart butterfly.” It really isn’t a butterfly because the two options being sold aren’t the same.

The broken wing condor is set up by buying a debit spread somewhat close to the money and selling a wider credit spread well out of the money. The credit spread has to have enough premium and width to collect more money than the debit spread costs. Depending on where the strikes are actually selected, the ratio of the widths may need to be 2:1 or even 3:1. Like all the other ratio trades on this page, this trade can be done with either puts or calls.

Like the previous two trades, there are two ways to win with this trade, either having all the options expire worthless so that the trader keeps the initial premium collected as profit, or ending between the two short strikes where profit is maximized. The second way actually has some decent probability of occurring, compared to the broken wing butterfly. Additionally, there is a third way to profit that can often come into play- as expiration approaches with the long debit spread within the expected move of the current price, there is a window in time where this trade can become more valuable than what it was originally sold for, even while it is out of the money. What happens is that the credit spread that is further away can decay more quickly than the much closer debit spread. There can be an opportunity to close the trade for another credit prior to expiration.

Of course there is a downside to all these positive traits. If the price blows through all the strikes in the trade, the max loss can be large, although still a defined risk.

With either of these broken wing trades, or even the front ratio spread, there are defensive tactics that can be used to defend a trade that has gone wrong. When most or all of the strikes are in the money, the long strike most in the money and the short strike closest to it can be considered an in-the-money debit spread, which can be sold. Then the remaining strikes can be rolled out in time with the expectation that price will reverse and make those positions profitable.

A more detailed explanation can be found in my post on Broken Wing Put Condors.

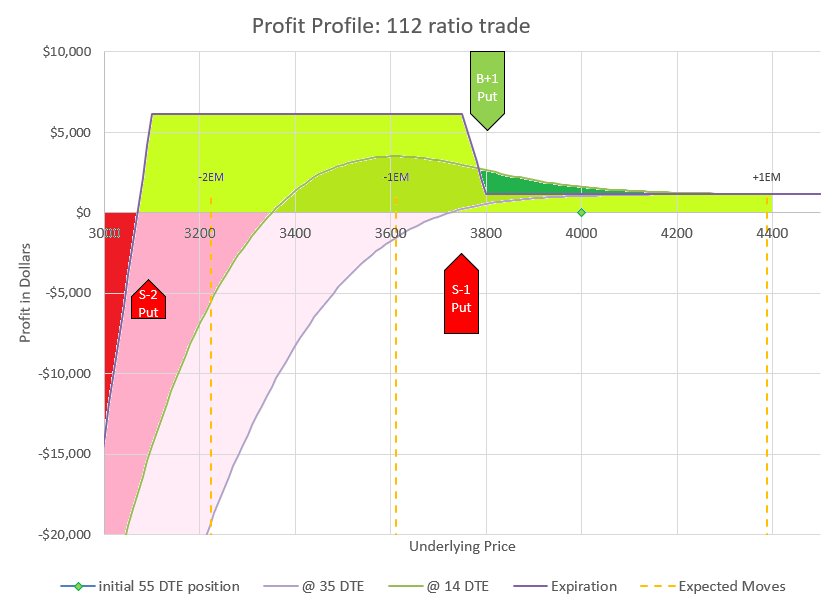

1-1-2 and 1-1-2-2 Put Ratio Trades

Why sell just one extra put when you can sell two more? Selling more puts allows a trader to sell far out of the money and still collect a credit with the right set-up. Whether this trade is done naked as 1-1-2, or defined risk as 1-1-2-2, the goal is the same- high probability of profit with rapid decay.

This trade can be a little capital intensive, and has a lot of moving parts, so it is best to read about it in detail in my post about 1-1-2-2 and 1-1-2 trades.

The Back Ratio Spread

The back ratio spread differs from the other strategies discussed in this page, because it has more long options than short. A standard strategy would be to buy two options and sell one in the same expiration.

Why would someone do this? Generally, the goal is to have the sold option pay for something that is a problem with the purchased option. Long/purchased options have time decay, positive Vega, and positive Delta for calls or negative Delta for puts. Depending on a trader’s perspective, any of these could be considered a risk that could be countered by selling an option with an opposite value. Let’s look at a couple of examples.

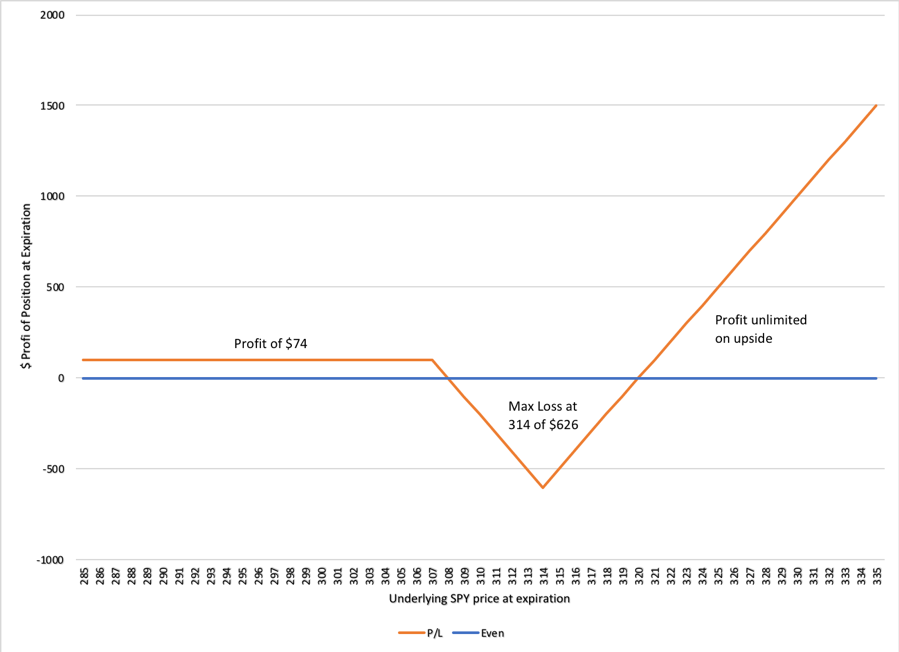

Zero Extrinsic Back Ratio (ZEBRA): When an option is purchased, part of the cost is paying for extrinsic/time value. From the moment the option is purchased until expiration, this value decays, eating away at the return. What if you could sell an option that would completely counter that time value, allowing the trade to move through time with virtually no impact from time, while getting the full benefit of price movement? This is the beauty of the ZEBRA trade, so named by Liz and Jenny of TastyTrade.com. By buying two 75 Delta options and selling one 50 Delta option, a trader can own a net 100 Delta position and have no extrinsic value. Typically, a 50 Delta option has about twice the extrinsic/time value as a 75 Delta option. However, the 75 Delta option has intrinsic value and the 50 Delta option has none. The end result is a position that moves in price the same as 100 shares of the underlying stock, but at a cost of 10-30% of the cost of owning shares. The cost depends on how far out the expiration is and the amount of Implied Volatility (IV) is present. So, this trade ends up with unlimited upside if the market goes in the direction of your long position (up for calls, down for puts), and has downside limited to the purchase price of the options. This trade can be used as a replacement for long stock by using calls, or for short stock by using puts. By itself, it is a leveraged way to own or short stock, with a limit to losses. By pairing with cash, the amount of leverage can be reduced all the way to being equivalent to stock with downside protection. This can be a compelling substitute for stock and as such is now one of my favorite trades.

Delta Neutral Back Ratio Spread: I first learned of this strategy from reading one of the most complete books on option strategies around, “McMillan on Options,” by Lawrence C. McMillan. What is there to do in a situation where there seems to be an equal chance of a big move up or a big move down? Maybe there’s been a big drop in the market, or the market is sitting at all time highs but could go either way quickly. How about a Delta neutral back ratio spread? In this case, we sell one option with twice the Delta as two that we buy. Perhaps we sell a 40 Delta option and buy two 20 Delta options. The option sold will collect more premium than the two options that were purchased. This works with calls or puts. The allure of this strategy is that the position starts out as Delta neutral- the two longs cancel out the one short. So whether the price goes up or down, the position doesn’t change much to start with because delta is zero. However, as the position moves further away from the starting price, delta will start to gain momentum in the direction of movement. If price goes up, Delta goes up; if price goes down, Delta goes down. Again, this is true whether the spread is done with calls or puts. The more the move, the better, but especially if price moves way beyond the strike price of the two long options. Profit is theoretically unlimited as the long strikes go into the money, and the trader may be able to collect a credit to close- a win-win. In the other direction, the goal is for the options to expire worthless, and the trader keeps the initial premium collected. The downside is if the price doesn’t move much and the short strikes are in the money and the longs are out of the money at expiration. The trader will have to buy the short option back at a loss, or the short options will be assigned at a loss.

Two very different trades, but both are back ratios with unlimited profit in one direction. Either type of trade can be done with puts or calls. The trade-off is that buying two options while selling just one generally means that Theta will be negative and the long options will decay faster than the short option. There are many considerations in choosing strikes and managing these trades, and I cover more of that in my favorite strategies section where I discuss each in more detail. There are other ways to set up back ratio spreads, but I think of these examples as the opposite ends of the spectrum of back spread strategies.

Ratio Conclusions

Ratio strategies take a lot of study to truly understand. Of all the trades that I’ve tried to explain to others, these are the ones that are most likely to stump people not familiar with them. Even this webpage of writing just scratches the surface in explaining the concepts of the various different trades. Since several of my favorite trades fall into this grouping, I’ll go into more detail elsewhere on the site to explain how I like to use these strategies, how I pick strikes, and how I manage them.

One unique attribute of these ratio strategies is that they can decay or grow much more rapidly in time than naked options or equal spreads. These differences are important to understand before trading, and it can often help to use analysis features of your trading platform to see how a specific trade will evolve between entry and expiration.

Ratios can be used to manipulate and manage specific Greeks in ways other trades can’t. Because the ratios can be used in or out of the money for different purposes, different traders may use the same base strategy in very different ways, not even considering other trades that may use the type of ratio at very different strikes. For example, I like to set up most of my strategies to have a relatively high probability of profit, while others may focus more on taking long shots that pay off much bigger. There’s no right or wrong way to use ratios, but whatever way is chosen needs to have a plan of attack to take advantage of the unique setup chosen and manage the risks of the trade.

One of the best options blog I have ever seen!!

When combined brcs and cps in your backtest, you open brcs 28dte and close 21 dte . But for cps ? Is it 45 dte close 21dte no edjustmen?

In your backrest what was the capital percentage being used? And how much for each strategy?

Tnx in advance.

Thanks for the kind words. For the back test, and for how I now like to trade this, I keep all the expirations the same, 28 DTE to 21 DTE, for both the Put Credit Spread and the Back Ratio Call Spread. That way, the two positions are using the same buying power, as they can’t both end up in the money, as long as none of the strikes overlap. If you trade them at different durations, your broker would likely require about twice as much capital.

So, for the backtest, on the two year test, I used SPX for the underlying, and it required just over $100,000. The two-year net profit was around $58,000, and the maximum drawdown was around $15,000. You should be able to get similar results with SPY for 1/10 the capital, although the backtest didn’t come out quite as strong- not sure why.

After replying, I went back to the backtest as I thought $100,000 was a lot of capital for this trade. I haven’t dug deep into Tasty’s raw data from the backtest, but the summary details show that the average buying power used during the backtest per trade was a little over $10,000. The backtest was opening a new trade every day and holding for 7 days, so that would take up an average of $50K or so. The max drawdown was around $15K, although the biggest individual trade loss was about $9K. When I get time, I’ll take all the raw data and do my own analysis, as there seems to be something a little funky about how Tasty calculates its cumulative returns and capital required.

Sorry I meant to post it on the last backratio backtest you’ve done