As a seller of options, and particularly option spreads, there is nothing that frustrates me more than losing money when the market is going up. The market goes up a lot, way more often than down. I like to play both sides of the trade with a neutral outlook, but I seem to get burned by price moves moving through my short call positions. Then I discovered the call back ratio spread.

The call back ratio spread is a position made up of a short call and two less expensive long calls. In most situations, this can be opened by collecting a credit to start the trade. This is the opposite of a traditional ratio spread, or front ratio, where a long option is financed with two cheaper short options. When done the way I do it, the position can make money if the underlying goes up or goes down. In fact, the upside to increasing underlying prices is unlimited, and the trade can sometimes close for an additional credit. You can actually sell for a credit to open, and close the trade by selling for a credit to close.

Of course, there is no free lunch. The flip side is that this trade can lose much more than the initial credit if the price doesn’t move or moves to the wrong spot. The trade is also susceptible to decreases in volatility. For many setups, time is not a friend to the position even though a credit is collected to start.

Calls don’t have a monopoly on back ratio spreads, as a back ratio spread can be created with puts as well. But, for most equities, and especially index exchange traded funds (ETFs), calls work better because of one attribute of the option chain- Implied Volatility Skew. Puts tend to have higher Implied Volatility due to often being priced higher than the risk that they represent. Calls have lower IV, and lower prices farther out of the money, making buying more attractive. Some underlying securities do have the opposite pricing situation, forward skew, where calls have higher IV than puts. In those cases, put back ratio spreads may be a good choice, instead of a call back ratio spread.

Note: While this original write-up from 2019 has had several updates, there is an additional updated write-up with more analysis written in 2025 to match with a YouTube video interview released on ThetaProfits.com. However, this original discussion has more details about variations of Back Ratio Call Spreads, so I think you’ll find both helpful.

The specifics

I typically open call back ratio spreads by selling a call out of the money, and then buying two calls that have half the Delta of the short call I sold. The logic is that the Deltas will add up to zero, and I’ll be Delta neutral. This means that initial price changes won’t impact the value of the position. Also, because of reverse skew in Implied Volatility, the long calls will be priced well under half the price of the short calls, so the net result will be a credit. So, the one short call more than pays for the two long calls.

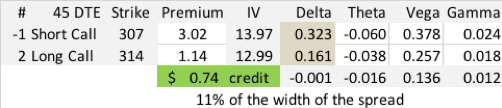

Let’s look at an example of this trade to see how it works. In late 2019, SPY was trading at $300 per share, and these options were available with 45 days until expiration (DTE).

Notice that the premium collected of $0.74 a share, or $74 per contract is 11% of the $7 width of the spread ($3.02-2x $1.14). This is generally about what I expect in these kinds of trades. Also, notice that the Delta value of the short call is almost exactly double the Delta value of the long calls. The position has a little negative Theta, which means that the value of the position will drop initially even though it is out of the money. Vega is positive, meaning that the value will go up if volatility increases.

Gamma takes on an interesting role in this position. Gamma measures the change in Delta for a one dollar change in the underlying. Since Delta is virtually zero, a move up in the price of SPY by one dollar will increase Delta by 0.012, or a decrease in price would move Delta negative by 0.012. So, Delta will move in the direction of price, and the more the price moves, the more Delta will move. If price is going down, we want a negative Delta, and if price is going up, we want a postive Delta. In this situation, we get the best of both. How is this possible?

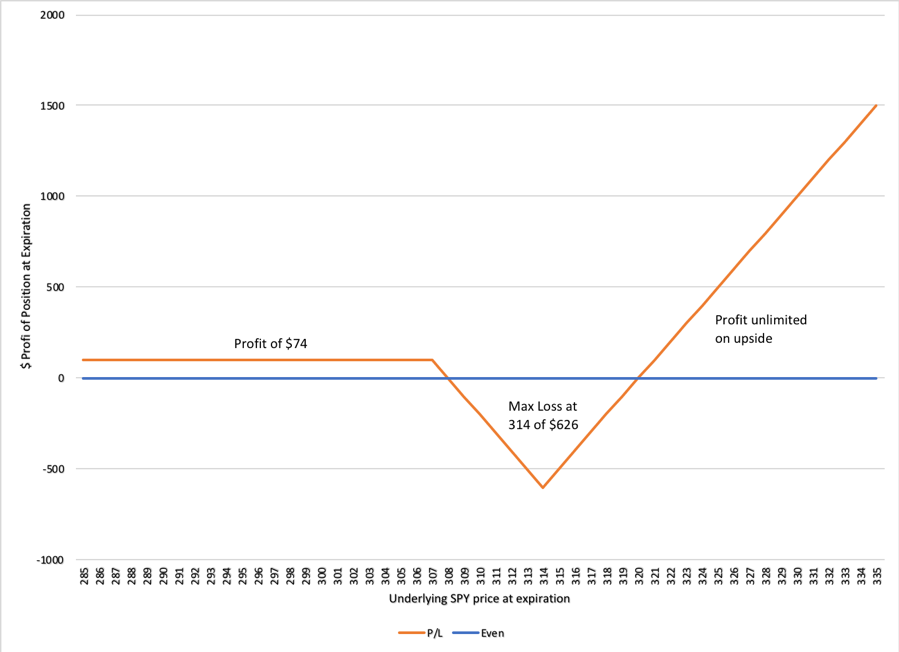

Since we are out of the money, a price decrease in SPY will make the premiums of both options decrease, and time decay will eventually drive them to zero. Moving away from the option strikes makes this happen faster. As long as the position expires out of the money, we can keep all of the $0.74 we collected when we opened the position.

On the other hand, as price increases, the two long calls start gaining in value faster than the one short option can gain. Eventually, if the SPY price goes high enough, like over 325, the position could approach going up a dollar for every dollar that SPY increases.

The problem area is if the price goes into the money and stops between the strikes. Time/Theta will eat away the value of the long calls and the short calls will have intrinsic value. If SPY closed at $314 on expiration, the value of the position would be -$7.00, a loss of $6.26 from our $0.74 credit originally collected. This is the worst case scenario.

Remember that we started this position with SPY trading at $300 per share. Our median or most likely outcome is a 1% increase in price to $303, which would keep the position out of the money. However, the expected move is 14, which would put us between 286 and 314. Since 314 is our max loss, we’ll want to avoid that. More than almost any other strategy, this position will require management.

Management of the call backspread

The goal of management is adjust strikes with rolls, mostly at the same expiration to pick new strikes that have neutral Delta, and collect a premium. This can usually be done many times, and often at a reduction of the spread. Sometimes, when the underlying drops enough, there isn’t a good roll to do, and the whole spread is worth much less than the cost basis, and it just makes sense to close the spread and start over.

Call backspreads work well with lots of time left, so that Theta doesn’t take as much from the two long calls. As expiration time approaches, it usually makes sense to roll to later expirations or close the spread, especially if the underlying price is in the middle of the spread.

In general, the more choppy the market, the more often it makes sense to adjust strikes. When prices are jumping up and down, a trader can capture gains going both up and down by adjusting back to neutral Delta, collecting additional premium all along the way.

When volatility is low, and the underlying price doesn’t move much, there isn’t a lot to do. The best low volatility situation is a steady melt up where the underlying climbs above the long strikes. This is where a call back ratio spread can make big returns. In this situation, there is a choice to make- let the profits ride and grow ever bigger, or adjust strikes to lock in gains, but somewhat reduce upside potential. There isn’t a right answer, it depends on the risk profile of the trader, and the market outlook. When I get in this situation, I generally let the market guide me by letting the position alone until something happens to really worry me- then I adjust or close.

The dreaded Death Valley

In case you think I glossed over the max loss part of the call backspread trade, this section is to address it. In our earlier example, the spread that was sold had a width of $7 between strikes, which equates to a maximum value of negative $700. Since the trade only collected 11% of the width, 89% of the width is at risk. When looking at the risk profile of the trade, there is a clear valley between the positive profit sides of the trade. I call this area the Death Valley of the backspread. To make a profit the trade has to either stay out of the valley, or get out of the valley. If a trader just lets the back ratio spread ride, it can get difficult to get out of the trade without a big loss.

However, two points to keep in mind to help reduce potential for loss. First, the maximum loss is if the position is held to expiration and the underlying is exactly at the long strikes at expiration. The odds of that happening are extremely slim- it might be close to the long strike, but to hit right on it- probably not. Oh, also remember, the goal is not to hold to expiration, so I don’t expect to ever take a max loss on a call backspread.

Second, the profit and loss at expiration only remotely resembles the profile for loss until expiration is close at hand. Initially, the position loses a small amount if price stays the same, but gains for a move in either direction. If time passes, like half the time to expiration and the price hasn’t moved, there will likely be a small loss, although if the short strike is well out of the money, the loss in premium may still be less than what was collected initially. In any case, the loss halfway between when the position was opened and expiration will likely be small, even with no adjustments to strikes. By making adjustments to keep Delta neutral, and closing early, losses should be minimized.

Generally, big losses come when a back ratio spread is opened close to expiration while IV is high, and the price moves to the Death Valley, and then volatility drops rapidly. For this reason, I am cautious about opening back ratio spreads when IV is high or close to expiration. If IV is high, I wait for the market to come up and IV to back down a significant amount, and then open positions with plenty of time left, so I have time to manage. No trade is foolproof, but opening at the right market condition, and managing appropriately will greatly improve outcomes.

Alternative entries

Call back ratio spreads are very flexible. While I often open them with both strikes out of the money, they also work with one strike in the money. (You can’t do a Delta neutral backspread with both strikes in the money- the longs would have a Delta over 50 and the short can’t have Delta over 100.) As an example of one strike in the money, an in the money short call with a 60 Delta could be paired with two 30 Delta long calls. This is much more of a neutral strategy than both calls out of the money. An expected move in either direction will make a nice return. Generally, these types of strikes will carry a bigger positive premium difference, so a down move can be profitable. The big advantage of this approach is that an up move gets into the unlimited profit zone more quickly. However, the position starts in Death Valley, so the price needs to move to avoid losses.

One slightly different approach is to make the back ratio Theta neutral. With a Delta neutral trade, theta is generally negative, dragging the position down at the start of the trade. Buying long strikes with half of the Theta as the short strike, Theta is neutral to start with. Specifically, I often buy strikes with the lowest IV in the option table, and then choose the short strike with twice the Theta value, often with long strike Delta of 10 and short strike Delta of 4. This trade collects a small credit, usually expiring worthless, but with the possibility of large gains on a big up move. The “valley of death” is also in play and must be managed.

Another form of Call Back Ratio Spread is the ZEBRA trade, or Zero Extrinsic Back Ratio championed by TastyTrade. This trade seeks to replace stock with options at a fraction of the price, by buying two 75 Delta calls and selling a 50 Delta call. The net result is zero extrinsic value, although the position starts with negative Theta because the 75 Delta long positions decay faster than 50 Delta shorts. The trade requires paying a debit, but starts with 100 Delta in the position or the equivalent of 100 shares of stock.

Combining with other strategies

A call back ratio spread can be combined with a credit put spread to take double advantage of risk. As long as the spreads don’t overlap, only one of the spreads can lose at expiration, similar to the logic of an iron condor. In fact, most brokerage software will see this position as an iron condor and an additional long call position.

Another way to use a call back ratio spread is to hedge a long equity position kind of like a covered call. A covered call uses one short call to collect a premium on 100 shares of an equity- a stock or ETF. In most accounts, there is no reason to prevent a trader from buying long calls as well further out of the money. Some people don’t like covered calls because covered calls limit the upside potential of an equity position. So, a call spread, or even a call back ratio spread adds upside potential without taking on any additional capital risk, and still allows premium to be collected. It is one of my other favorite trades.

Bottom line

The call back ratio spread is one of my favorite trades because it works well with my underlying view of option trading. It works well when expiration dates are several weeks to several months away. It works well for traders that don’t have a market bias up or down. It does take attention, but really, any option trade requires attention.

There are lots of other types of ratio spreads that can be useful, and other ways to set up back ratio spreads in particular. See my page on ratio spreads to explore further.

I read your description of backspreads thank you,

My question is about put backspreads, when you sell more of the higher strike and buy more of the lower strike, you get an upside down put spread. and the stock goes up you collect

the value of the decline in price of the options. I tested this on OPTIONS PROFIT COLULATOR, IT looks very good to collect those gains in the lost of the puts going down.

your knowledge please.

Second, I have watched a bunch of videos and they say different things. on the margin needed to trade backspreads.

one is that there is no collateral on a backspread

the next is that you have to put up the money of the spread. between the strikes

the next one is that you have to have in your account the money to buy the 100 shares per contract that your trading options on.

Please explain which one is correct. thank you.

Also there is the 2-1 3-1 6-4 ratio. which one is correct. is there a matter here in that if you come up with a credit, on say a 2-1 thats ok and if it shows a selling 6- and buying 1 the credit is ok or do you have to put up margin as thats really like 4 of them being nuked?

please explain.

Also if you would name the broker that allows the way of your answers. thank you.

respectfully gs

Thanks for the note.

Backspreads can be used in different ways, but the idea is that you are buying two and selling one.

If the two you buy are more expensive than the one you sell, then the trade is a debit and your max loss is the amount paid- so no additional capital requirement. A popular version of this is the Zero Extrinsic Back Ratio or ZEBRA, where you buy two 75 delta calls and buy a 50 delta call. The net is that you have 100 delta total and virtually zero extrinsic value. You have the equivalent of 100 shares of stock and all the upside, but only 15-25% of the downside. There’s a little more nuance to it, but it is the back ratio that many use. The reverse can be done with puts as well.

However, if you collect more than you pay, as in a delta neutral spread like I have described, then you are risking the difference of the strikes in the spread. This is the trade that McMillan describes in his classic book on options. So if you sell a 100 strike and buy two 110 strikes at half the delta, you’ll collect a credit, but you have $10 risk, which your broker will require in margin. However, if you have a credit put spread on the same expiration at lower strikes, you’ll only risk the wider of the two spreads, as that is the max you can lose. I find that the brokers I have used don’t recognize these trades as back spreads, but as a credit spread plus a long call, which from a margin standpoint is still correct. This caused me some grief with Schwab when I put some of these on using index options in a retirement account. When I tried to open more than one of these, Schwab’s system recognized these as calendar spreads and rejected them, as calendar spreads are not allowed on index options like SPX in a retirement account. I had to call support every time to get the trade approved, and I finally just got tired of it.

The delta neutral trade that I have written about requires a lot of movement in the underlying to make money. If not, there is a lot of extrinsic/time value that can evaporate quickly, particularly if there isn’t a lot of time to expiration. So, I’ve found that it works best when markets are crazy and you continue to expect high volatility for a while, or when volatility is at extremely low levels and you are hoping for a big move. The watch out in either case is not to get caught in the “valley of death” as many call it where you take max loss at expiration. To get profitable at expiration, the strikes need to either move away from the valley or cross it. At first, you may not lose much, but every day you lose some if the price stays in the valley. So, this version of back ratio is not a trade for every season, and I’m now much more selective in when to apply it.

Thank you for your post(s), I find setting delta neutral at start is very useful for both call/put back.

Hello,

Thank you for these valuable education materials. Could you please give an example of management where delta is made neutral while the underlying is moving up or down? Can this work in both ITM and OTM combo or only in OTM combos?

Thanks

Great question. Let’s say we open a back ratio call spread in SPY, selling a 40 delta call and buying two 20 delta calls. We collect a net credit of $2.32 to open. The position is delta neutral.

Shortly after opening, the market goes up 2.5% and our positions have increased in delta. After the move, our short strike has a delta of 52 and our two long strikes have a delta of 30. In total we now have a positive 8 delta. The position value is now $2.01, so we’ve made $0.31 from the move. To adjust back to neutral, we can close our current position and open a similar position again selling a 40 delta strike and buying two 20 delta strikes to get to delta neutral. We collect $0.33 net credit for the combined transaction.

On the other hand, if the market drops 2.5% shortly after opening the original trade, our position deltas will get lower. After the down move, our short strike has a delta of 28 and the two longs have a delta of 12, so our position is now negative 4 delta. Our position value drops to $1.99 so we have a profit of $0.33 from the move. To make this position delta neutral, we can roll down our strikes, closing our existing position and selling a new 40 delta call and buying two new 20 delta calls, getting back to neutral. In this rolling trade, we collect a net $0.36 credit.

So, either way the market goes, our neutral back ratio changes to favor a move in that direction. How cool is that? But, the downside is that if the market doesn’t move, the position loses ground because the two long calls lose value faster than the one short call. The Theta value of the initial position is -0.045. Holding the back ratio will result in significant losses if the underlying price doesn’t move.

Even if the price moves, it can be prudent to evaluate the position to decide whether to close, adjust, or let it ride. If you suspect that the move is complete and won’t move much more either way, close the trade before negative theta eats away your gain. If you expect a likely reversal, or more big, short-term moves in an unknown direction, adjust back to neutral delta. If you expect the price to continue in the direction it has already moved, let it ride with the directional delta you have acquired. This is not a trade to open and forget about. It takes active management and decision-making.

Hey there! This is an exciting strategy and I’d love to test it out!

Regarding managing due to moves in the underlying, are you adjusting the strikes to get back to neutral once the position reaches a certain delta? Or maybe if the overall price of the position changes (either increasing or decreasing)?

Regarding management by time, are you then also closing/rolling regardless of the underlying move at a fixed date (ex: 21 DTE) to keep the greek exposure relatively muted?

Thanks for the nice comment.

The thing to always remember with a back ratio spread is that time is generally not on your side, so it is important to evaluate whether you want to stay in the trade, a modified version of the trade, or get out when circumstances change. This trade works when the market moves one way or another, but not if the market stands still. There are some situations and set ups that will be profitable in the end with no movement, and I like to be in that position if time is running out.

I do like to get back to neutral after a big move. It serves two purposes. First, it lets me harvest most of the gain I’ve made from the move before the market has a chance to take it back from me. Second, I get back to a place where I don’t care which way the market goes and reduce volatility of my account by being neutral.

Yes, I will generally look to either roll or get out by 21 days to avoid the rapid decay at the end of this trade. However, if my strikes are both well out of the money and I’m in a trade that I would have to pay to get out, I’d lean towards letting the trade expire worthless. If my position has value that I can sell, then I definitely want to avoid time decay. So, it depends a lot on what my original set up was and where my position is as 21 days approaches. Every back ratio trade has a strike area that has a valley of loss that you don’t want to be in as expiration approaches- you need to do something: get out of the trade, move out of the valley, or get more time; or you are likely to be stuck with a max loss.

But if a trader wants to roll the dice, one can stay with an in the money position that is growing in Delta and try to ride a trend to compound a win and not adjust or close. If the long strikes get significantly in the money, Theta becomes smaller and the longs start acting like stock.

This trade can go many ways, so figuring out a plan that matches your risk tolerance and comfort with each scenario is a personal decision. If you know the metrics and the probabilities as the trade progresses, you can assess the risk and reward of the different choices you have at any point in time.

Hello good sir! Greetings from Poland. I’m big fan of your work and wisdom, you publish here. Can you write some more, how do you combine that spread with credit put spread?

Thanks for the kind words.

For a call back ratio spread in combination with a put credit spread, I like to use the Delta neutral version. I pick strikes that are above the put strikes in the same expiration. I look for a width the same as the put spread that also has a short call strike with a Delta twice the Delta value of the long call strikes. I’m hoping for a big move because Theta will be negative to start with. I then manage using the mechanics written in the page on this trade.

Thank you for your answer.

But how do you combine it to be delta neutral? Back ratio spread is already delta neutral, when you sell call for „x” and then you buy 2 calls for „half of the x”. Do you just don’t keep it that way, when you want to combine it with cps?

I like this kind of hedging at least a portion of your credit spread if the market goes down and in best case profiting twice if the market pops up. Did you ever focused on hedging your credit put spreads with going long on VIX e.g. using a debit spread? What is your opinion to that?

Kind regards!

Chris

Chris- Hedging with VIX options is very tricky. Because VIX is a derivative of a derivitive, and also based on futures for any expirations of any duration, they behave in ways that aren’t as predictable as one would expect. Add to that the issue of knowing when to cash in a debit spread when the market goes bad. If you get out early, you miss the benefit. If you get out late, you miss the profit. It’s not impossible, but there are a lot of variables that make trades like that very complex.

Hi Carl!

First of all, I love your articles, especially that they go so deep.

I run the website https://thetaprofits.com One feature there is that I do regular video interviews with other retail traders.

I would love to do an interview with you about this strategy – or one of your other favorite strategies.

Would that be of interest for you?

Feel free to email me – or respond here.

Thanks a lot for your consideration!

John Einar Sandvand

Carl, Hello. Thanks for sharing what you learned. I found you on Theta Profits. I wondering if you have had heard of the ZEEBHS trade and how it compares to CPS + BRCS (you can find it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YHggVlYlYZA&t=130s or search on youtube: Best Long Strategy with Hedge – ZEEHBS Options Trading Strategy) I didn’t back test it but I tried a few times but kept losing money. I like the idea of it and maybe it works better on your 28 –> 21 DTE vs their 7 DTE – I think you are supposed to roll it ever 2 days? Could you back test on 28 to 21 DTE and compare the other strategies in your Theta Profit video. It would be much appreciated. Thanks.

Patrick- yes, I remember watching Tony from Mexico explain this ZEEHBS trade several years ago. The concept is very similar in many ways, but with more theoretical downside protection. However, my quick look at backtests doesn’t show the trade doing that well in down markets. The Tasty backtest showed a big loss during the 2022 bear market, probably because the market was a slow grind down with no huge down crashes. It looks to have about broken even during Covid, as the put protection would have kicked in on the down moves. During bull markets it appears to have performed pretty well, which should be expected as it is primarily built for up moves. The downside of the trade is the potential for a lot of little losses from positions ending up in the valley of loss.

Like you, I tried the trade for a while, but all the mechanics became a bit much for me and the timing was not good as I took several losses in a row. I don’t really have an opinion on the trade, and I haven’t studied it in much detail, other than to do a quick backtest as you suggested. The video you linked is a really great explanation of the trade, more clear than even Tony explained it back in the time it became popular.