What level of option risk goes best with what type of underlying security? Most people reading this might wonder what in the world is the point of this topic and why should I care? Depending on the option strategy, your choice of underlying security type can have a big impact on your outcomes. This might get a little deep, but hang with me and I think it will be worth your time.

4 risk levels, 4 underlying types

Brokers typical allow customers to trade options at four different levels of risk. I’ve written about how the risk compares between these levels. As a reminder the four levels are:

- Level 0: Covered options- cash secured puts and covered calls

- Level 1: Buy options

- Level 2: Option spread trades- buy an option, sell an option

- Level 3: Naked option selling

There are also four general types of underlying securities for trading options. With each comes different advantages and disadvantages. As a reminder the four types are:

- Individual Stocks of Companies

- Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs)

- Index Options

- Futures

For example, there are three different classes of underlying securities for trading options on the S&P 500 index: ETF options like SPY, Index options like $SPX, and Futures options like /ES.

So the question and point of this post is to examine which risk permission levels work best with which types of underlyings. It’s not an obvious question or an obvious answer. Most traders would say it doesn’t really matter- more risk is more risk, and less risk is less risk. But some underlyings are better built for certain strategies more than others. It doesn’t mean you can’t trade a strategy for a certain underlying, it is more of a question of what is optimal for the type of risk and potential return you are seeking in a trade.

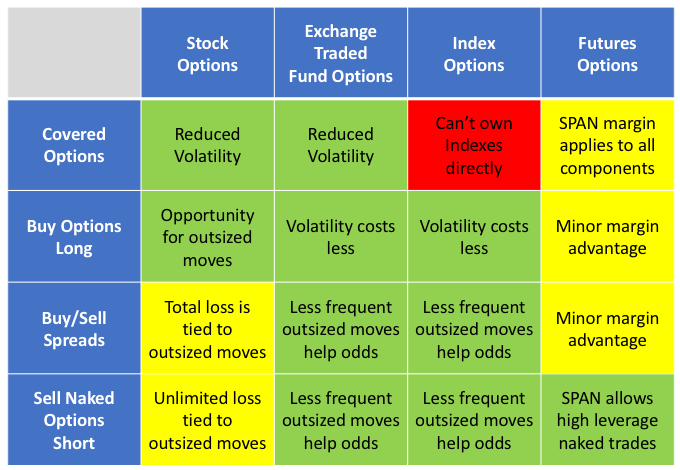

The Matrix

I made a sixteen square matrix to evaluate each combination. I rated each pairing based on how well the option risk matched with the characteristics of the underlying. My conclusions are simply my opinions, and I welcome discussion and other opinions backed by data. So here is my matrix and what follows is the data and logic behind it.

Let’s review the boxes one row at a time, by risk level.

Covered Options

Covered or secured option strategies include covered calls, cash secured puts, covered strangles, and the wheel strategy. These strategies use the full value of underlying shares either in cash or shares to protect against loss from selling short options. The options being sold are much less volatile than the value of shares, so covered options are the only option choice that is a clear reduction in risk compared to owning shares outright. All versions of this option trading strategy limit upside growth while allowing the potential of losses to zero, but most of the time these strategies outperform owning stock outright. So how does this type of transaction impact different underlyings?

Individual stocks can be very volatile. Positive or negative news about earnings or products or lawsuits or mergers or management changes can make stocks move way outside their expected moves. These outsized moves happen more often than normal statistical distributions would predict. Even so, individual stocks tend to have options with much higher implied volatility than the overall market. For stock investors that want to dampen day to day moves of their portfolio balances, selling secured or covered options is a great way to participate in individual stocks with less drama. Because of the crazy volatility of individual stocks and the high implied volatility of options on individual stocks, covered options are a great match for individual stocks.

I would argue that for both the covered strategy and the stock underlying type, this is the strongest match in this row and column. There is no better underlying for covered options than individual stock, and there is no better option risk level for individual stock. I know a lot of people will disagree, but as we look at the other combinations, I hope you’ll at least understand my point of view.

Covered options on exchange traded funds are fine trades. It’s probably the safest possible option strategy there is if we want to call any kind of trading “safe.” We combine a bunch of volatile stocks together into a product that dampens volatility down substantially. Then we sell options against that new product that will rarely see moves outside the moves that are expected. The options may not pay a lot, but they won’t lose often either. A very boring way to make steady gains (and I’m thinking of boring as a good word here).

An argument could be made that covered options on ETFs is perfect for both, because it’s a double volatility reduction, and for risk-averse traders that’s a great combination. I get that, but for me, I think it’s a little too much volatility reduction, and sacrifices too much option premium for safety. Be less volatile with stocks by selling covered options, or be less volatile with riskier option strategies by using ETFs, not both. But I’m generally a risk taker, so maybe I under-appreciate the double volatility reduction of covered option strategies with ETFs.

Covered options on indexes is the easiest combination to rate on the matrix, because it is the one combination that can’t be done. We can’t own an index outright, so we can’t sell a covered call. If we sell a put and get assigned we don’t get the index, we just pay up the cash we lost. So, there isn’t a real way to sell covered index options on the underlying index. This is the only red square in the matrix because it can’t be done.

Covered options on futures can be done, but it doesn’t really make sense. Futures and futures options are all governed by span margin, so really there isn’t an official way to sell covered options on futures, because there is margin being used on every leg of the trade. No piece is fully “covered.”

I almost made the covered futures options block red, but you can kind of do it if you set aside the cash that the full notional value of the future is worth when you sell a call against a future, or sell a put on a futures contract. The problem is that your buying power won’t show that you’ve locked up the full notional value, so you have to track it yourself. It just isn’t what futures are about.

Let’s do a quick example to illustrate. Let’s say we have a futures product that trades for $1000 with a multiplier of 50. So the notional value of a contract is $50,000. If we buy a futures contract, the broker will use SPAN margin and only take away at most $10,000 of our buying power, even though we are on the hook for the full $50,000. If we sell a call on the same future, we’ll likely gain buying power, as we just reduced the volatility of the position. Maybe SPAN margin says we now only need $5,000 buying power, while we remain at risk for $50,000. So, our broker and SPAN margin don’t make us “cover” our options. You can keep $50,000 in your account to cover the trade yourself, but nothing forces you to, other than wanting to eliminate any risk of blowing up your account in a downturn. It’s fine to do this, but it technically isn’t a covered option, so it’s a yellow square on my matrix.

Buying options

When most people first learn about options, buying an option is the trade they can easily understand. You pay a premium to have the option to either buy or sell something. Margin is not a factor, because the risk is defined. The risk of the option is the cost, it can end up worthless, a total loss, but no more than what was paid to own the option. If the option ends up in the money, it may be profitable, maybe very profitable. Leverage comes from the possibility of virtually unlimited profit for a relatively low cost.

Buying puts or calls is like going to the security market casino. It’s a low probability bet that might pay off big, but often will lose what you gambled. But let’s not get all “judgy” against the strategy- lots of directional traders buy options to get the most out of a move they think will come. When implied volatility is low and the market is rolling up nice gains, it can be a very lucrative trade that exceeds its predicted probability. But which underlying security types are best fit to take advantage?

Individual stocks can make big moves up or down, and owning an option in the right direction when a big move happens can be great! But the market knows that individual stocks are prone to big moves so options are expensive to buy. A little move won’t cut it. A trader has to be very right on timing and direction.

But, if buying calls or puts is your thing, the biggest rewards are with individual stocks. So, I’ll give it a green square.

Buying options on ETFs is cheaper than stocks, but the likely moves won’t be as big. However, if the goal is to ride a trend that is going up faster than what implied volatility predicts or a slide going down, ETF long options are a good choice.

In a bull market, selling calls is usually a loser, which means that buying calls can be a winner. Buying calls on an ETF in a bull market will hit a lot of winners usually without a lot of capital required, so probably the best use of the strategy in this row.

Buying put and call index options is a very similar situation as options on ETFs. It’s really a matter of preference, depending on several factors. Some brokers restrict access to index options, so it might not even be a choice for some accounts. Most index options are bigger notional value, often 10 times as big as the equivalent ETF, so it might make more sense for a bigger account to use index options, while smaller accounts stick to ETFs. There are a lot more ETFs available than index options, so niche indexes either don’t have an index option or have such poor liquidity that the only choice is an ETF. Commissions per contract are often higher on index options, but per notional amount are lower. So, it depends on a lot of things. I’ve discussed the differences in much more detail in my write-up of different ways to trade the S&P 500. All the same trade-offs are true for the Nasdaq 100 and Russell 2000. So, for some traders buying options, the index option might be best so I’m coloring the combination green, but for most traders smaller, more liquid ETFs are going to be a better choice.

For futures options, the issues are similar as comparing index options to ETF options, except that buying futures options outright negates much of the advantages of futures options, but keeps the negatives. Futures options are a favorite of experienced and sophisticated traders because they can be traded with lower SPAN margin requirements, giving a trader more leverage, and also letting opposing positions reduce buying power. But, if a trader is only buying options, buying future options doesn’t gain much in buying power, but will cost a lot more in commissions and slippage from lesser liquidity than ETFs or index options. In my opinion the only time it makes sense to buy a futures option is to counter a bunch of short futures options or other futures position. I talked about this in my discussion of buying the 1 DTE straddle with futures options.

In the end, unless you have a really good reason to buy options on futures, it generally is a better trade to buy a similar ETF or index option product. So that’s why I colored this combination yellow.

Trading Option Spreads

Let’s define an option spread as buying and selling an equal number of puts or calls. There are a lot of ways to trade spreads, and many of my favorite strategies fall in this broad risk category. Option spreads have defined risk, but as strategies get more complex, understanding exactly how much risk a trade has defined can get a little tricky. It isn’t as obvious as the risk with buying an option, but the risk is known.

We can think of spreads in two main categories, debit and credit spreads. Debit spreads are trades where a trader pays to enter the trade, and credit spreads pay the trader to enter the trade. Credit spreads are often the highest leverage version of selling options, with the highest potential return on capital for many positions. With that potential high return on capital comes the risk of a total loss, often many times the amount that was collected to open the trade. How do these factors impact different underlyings?

With individual stocks having more likelihood of an outsized move, there is a bigger chance of a total loss on a credit spread, although that is somewhat balanced by higher premium from higher implied volatility. Debit spreads tend to limit max gain in exchange for improved probabilities compared to buying options outright. So, debit spreads on a individual stock miss out on big gains without a outsized increase in probability of profit.

Many traders favor spreads for individual stocks over naked options because of the defined risk limiting losses to a defined amount. My view is that both strategies have to contend with outsized moves and it’s a matter of picking which poison does the least damage. But because so many like spreads as a risk reduction for individual stock options and it is a viable strategy, I’ll rate this combination a yellow.

I’m going to lump ETF options and index options together for spreads. Just like with the earlier discussion on buying options, the difference between ETFs and indexes is a matter of preference and an individual’s account situations. Strategically, I like both for buying and selling spreads. Because ETFs and indexes are made up of many stocks, they have much fewer out-sized moves than individual stocks. This makes the leverage of spread trading work well, both in credit and debit type spreads.

In particular, selling put spreads on ETFs and indexes can be a high probability trade. I’ve written about this my page on selling put spreads. I’ve also written about the best delta for put spreads, and the best deltas for rolling put spreads. And in each case, I tend to stick to some version of a put spread on the S&P 500. I’ll add a call spread to turn the trade into an Iron Condor, which I’ve discussed in my post on rolling Iron Condors.

As for buying spreads, I’ll occasionally buy a call spread when the market is particularly bullish and Implied Volatility is low. Buying options in any style is usually a low probability trade, but there are ways to improve odds, and using a spread to have decay on the short leg off-setting the decay being lost on the long leg can be a big help. We can get more exotic with diagonal trades selling a nearer term option while buying a longer term option and actually having positive Theta for our trouble. In all these trades I like ETFs and indexes because the results tend to be more consistent.

Many of the ratio type trades that I do utilize two sets of spreads, like the popular broken wing butterfly trade. Again, I like ETFs and indexes because outsized moves are less likely than individual stocks.

You may be sensing a theme. Less outsized moves make using the highly leveraged option spread on ETFs and indexes my favorite choice for spread trades. It’s green squares for both, and my favorite use of ETFs and indexes, as well as my favorite way to trade spreads.

In theory, futures option trades with spreads should also be as favorable as ETFs and indexes. They work about the same and have the same type of probabilities. But there are two things that I don’t like about trading spreads on futures. One is a personal nit-picky concern, and one is a concern that virtually any trader would have.

Let’s start with the most legitimate concern. Futures options are less liquid than ETF and index options. They have wider bid-ask spreads, and they are harder to fill close to the mid price between the bid and ask. In many trades, the tick size, or the amount you can adjust your limit price by is substantially bigger than for the same trade on an index option on the same thing. For example, on $SPX index, we can adjust our limit orders by 5 cents up or down, but with /ES futures, we have to adjust our order in increments of 25 cents. To make it worse, often the volumes are much lower and even giving up 25 cents won’t get an order filled. So, it can cost a lot to get filled, and we haven’t even talked about commissions, which are generally also higher, both per contract, and even more so as percentage of the notional value of the position. Maybe someday these costs will get lower and it won’t bother me as much, but I just don’t like it for spreads with futures options.

But what about SPAN margin you might ask? Doesn’t that extra margin make it palatable to pay a little more so you can get that super-duper leverage for traders that like more risk and more reward? Well, this is my nit-picky problem with spreads on futures. SPAN margin isn’t that much extra buying power for spreads with futures options compared to indexes, ETFs, and individual stocks. Because spreads have defined risk, the two sides of the trade already have formed a hedge and SPAN margin doesn’t give much more buying power than the reduction from calculating the max loss of the total spread being wiped out. To be fair, futures traders get some additional buying power, but it isn’t enough for me to justify the higher costs of trading spreads with futures options.

I know there are traders out there that like futures with spreads that little extra buying power that comes from SPAN margin, but for me it makes more sense to go with an index option or ETF option where my risk is defined and doesn’t change. So, I’m giving this spot on the matrix a yellow. Proceed with caution.

Selling Naked Options

Selling naked options is supposed to be the riskiest of the whole bunch of risky option trades. In one way it is in that maximum losses are essentially undefined, but even with margin, the leverage of Theta or Delta as a percentage of buying power is often less than what happens with spreads. So, as long as we avoid outsized moves (which we can’t, by the way) there’s a strong argument that selling naked options is not nearly as risky as it would seem at first glance.

Let’s be clear about what selling a naked option is about. With covered options, we can sell a call or a put and there is either cash or shares covering the short option positions. For naked trades, the broker lets us sell on margin. Often we are only required to have something like 20% of the notional value set aside for covering the option sale. That’s great for our account as long as the price doesn’t move against us more than that 20%. Actually, the broker will increase buying power requirements as price moves against a position, so the requirements are always in flux. But with plenty of extra cash as a buffer and markets not going crazy, it’s manageable.

So, we are selling options on margin. What underlying type does this work best with? Let’s check out our four choices.

Individual stocks are the most likely underlying to have an outsized move, so they are the most likely to get a naked option trade into trouble. It doesn’t take much, a change at CEO, a merger or acquisition, surprising earnings announcements, good or bad product news- any of these can trigger a move way beyond the expected move. With individual stocks, the probability of an outsized move both up or down tends to be greater that what Delta would predict, or it often just isn’t that great compared to the other products with diversified components.

That’s my reason for avoiding naked options on individual stocks. I know lots of people trade naked options on stocks all the time, diversifying their holdings to reduce overall risk. But for me, why not use an underlying that is already diversified? I know individual stocks have higher Implied Volatility to pay a seller to take on that added tail risk, but for me it just isn’t enough. I’ve seen too many situations where a trader has gotten a very nasty surprise and lost way more than they thought they could. It can happen with any naked trade, but it’s more likely with individual stock options. So, for me this is a yellow box- proceed with extreme caution.

Now, let’s not try to make the argument that naked options on the other types of underlyings are super safe. They aren’t, and you can lose big. Ask anyone who had naked puts on the S&P 500 (any version) when Covid hit in 2020. It was bad. But those kinds of moves happen much less often than negative moves in individual stocks. People that trade naked options take a lot of risk, and so the question for the remaining three underlying types isn’t which one is least risky, but which gives you the biggest bang for the buck? If you are selling naked options, you better know what the risk is, but how do you maximize return when you have a trade go your way?

Like the last two levels of risk, ETFs and index options have essentially the same pros and cons for naked options. While there is significant tail risk, it isn’t as high as individual stocks. So, naked options sales on ETFs and indexes tend to perform better than the expected move would predict. This makes these underlyings a better choice for underlyings on naked options. As a result, I’m giving these matrix squares a green rating.

Finally, we have selling naked futures options. On one hand this is a highly leveraged trade with ultimate tail risk due to SPAN margining. On the other hand, this combination gives a trader the potential for significant high returns on high probability trades that otherwise might not make sense.

I look at naked futures options as the ultimate “go big or go home” trade. If a trader wants to trade futures options, selling naked gives the ultimate amount of exposure for the least buying power. SPAN margin allows a trader to use a fairly small amount of capital to open a naked trade. And if a trader balances the Delta of both sides of a trade, buying power requirements become even less, as the total risk is considered in required capital.

SPAN margin also lets a trader have different sides of the trade be at different expirations and have the net exposure of each side be considered in the SPAN margin calculation. The point is that for the most agressive, risk-tolerant option trader, there is no higher leverage way to sell options than selling naked options on futures. For that reason, I really like futures for naked options.

Selling futures options naked still have the issue of poor liquidity and higher commissions, but the flexibility of SPAN margin finally makes it worth the cost for risk-tolerant traders. It is worth noting that the liquidity and commissions are significantly more of an issue for traders that trade “micro” versions of futures options, like /MES, compared to /ES. Whether it is a futures product on an stock index, a commodity, or a currency, the micro versions just have a lot less open interest and liquidity. So, if account size limits trades to micro futures, a trader has to watch which expirations and strikes can be entered and exited without huge price slippage, particularly when exiting early.

Despite the cost issues with futures options, selling naked futures is my favorite use of futures options, and my favorite way to sell options naked. I give it a green box on the matrix. I don’t rate it this way to suggest it is a safe trade, but that it is the ultimate use of options leverage.

Bonus sections

There are a few option strategies that don’t fit neatly into the four categories of risk that I think deserve a special mention because I talk about them in other parts of the site.

Bonus #1 Ratio Style Trades

Ratio style trades are a more complicated type of strategy where there is an unbalanced number of contracts sold vs bought- a lot of times a 2:1 ratio in some variation. If there are more contracts sold than bought, the trade becomes a level 3 naked trade, like the 1:1:1 or 1:1:2 put ratio trade that I discussed in other pages. But often, I use a level 2 defined risk version of the trade by adding long options to equal out the short options, usually creating a wide credit spread along with a narrow debit spread, like a broken wing butterfly (1:2:1), broken wing put condor (1:1:1:1), or 1:1:2:2 put ratio.

These trades are technically either a group of spreads (level 2), or a spread with a naked short option (level 3), but is there a difference in what underlyings are best for these kinds of trades because of the ratios and odd ways of managing these types of trades? The short answer is not really.

For level 2 defined risk ratio trades like butterflies, condors, and 1:1:2:2 trades, I like ETF and index options for their liquidity and reduced volatility. This is the same logic as with spread trades in general.

For level 3 naked versions of ratio trades where there are more short options than long, my preferred underlying is futures options due to the reduced buying power of SPAN margin. These trades tend to be fairly highly probability of profit, but with significant tail risk from black swan type events. SPAN margin considers this risk and allows a trader to use a fairly small amount of capital to enter this kind of trade. Anyone trading this way must consider the significant tail risk into their management strategy.

A trader can use ETF or index options for these naked ratio trades, but they consume a lot of capital with standard option margining. Traders with portfolio margin accounts might find this more acceptable. For understanding of different types of margin in options, see my post on the topic.

Bonus #2: 0 DTE trades

0 DTE trades have special considerations because of their short time frame. Let’s throw in 1 DTE and any options trade that has just a few days until expiration. All these trades focus on either last minute moves or the extreme decay that comes in the final days or hours of an option contract.

Individual stock options don’t have daily expirations, so expiration day trades are usually limited to Fridays or end of month at most. That essentially eliminates them as a candidate, but it gets worse.

With options near expiration, assignment at expiration or near expiration is a big concern. Individual stock options and ETFs in the money can be unexpectedly assigned into shares in the days before the options expire. And if options are held to the end of the expiration day, assignment can happen even if the market closes with options out of the money. A late after the market news event could trigger option holders to exercise their options on individual and ETF options, so you never know.

So, that leaves index and futures options. Index options are settled to cash at the market close. Futures options expire into futures contracts at the market close. A trader doesn’t have to worry about after market events impacting an expired position. The only exception to this is monthly index options that settle on the open of the market, but stop trading at the market close of the previous day. These contracts have AM expiration, where almost all other options expire in the PM, at the market close. The ticker symbols for index options expiring and settling at the market close generally end with a “W” for weekly, which originally was for the weekly expirations that happened every week, but now happen every day. The monthly options, which are the very original index options, don’t have a “W” at the end of their ticker indication.

Settling to cash vs settling to futures contracts or shares is a big difference. Most expiration day traders don’t want to deal with the underlying securities ending up in their account and the significant notional value that comes with them. Because of that, index options are far better choices for trades approaching expiration.

Traders with small accounts can choose between micro index options, like $XSP, micro futures options like /MES, or ETFs like SPY. They have different pros and cons. Micro index options have fairly poor liquidity with wide bid/ask spreads and big tick sizes for poor fills, but settle to cash at expiration. Micro futures options have worse liquidity and bid/ask spreads, plus high commissions, and settle to futures contracts, all negatives, but are usually half the notional size of the other two low capital choices. ETF options tend to have good liquidity, but settle to shares at expiration, or after expiration. None of these are ideal, but if a trader wants a small option stake on expiration day, these are the choices to consider.

Conclusion

So, there you have it. A fairly exhaustive analysis of the various combinations of trade types vs underlying security types. Some of the factors I consider most important in this analysis, may be less important to other traders, and some accounts at certain brokers may not even give a trader a choice to have some of these types of underlyings available. Others may not have some risk permissions available.

In any case, my hope is that whatever level of risk or underlyings a trader has available, it is clear what combinations make might more sense from a viewpoint of risk, potential reward, capital usage, and trading costs.

One thought on “Underlying Security vs Risk Permission”