This most extreme diagonal trade pairs buying a very long duration put that has almost no time decay with the sale of a very short duration put that can be rolled on a daily basis as it decays extensively in value. The main goal is make significant income from time decay of the short duration short put, while using the long duration put as a hedge. However, as we’ll see, there is a lot to consider, and many choices on setup and management of this trade.

A strategy that contrasts the extremes of option trading

A more descriptive title of this trade might be “The very long long and very short short rolling covered put diagonal trade.” Or maybe a simpler name would be a “Poor Man’s Covered Put.” This trade strategy contains a little bit of everything and has so many choices to consider and possible ways to manage that I’ve hesitated to write about it. On the other hand, more than any other trade, it illustrates many concepts in ways that allows them to be highlighted like in no other trade.

I always want to give credit where credit is due. I learned about this trade from my trading acquaintance, Jim Olsen, a veteran options trader with a constant quest for a different edge. He became interested in this trade mainly because he saw an opportunity to take advantage of the fact that deep in the money puts have little extrinsic value, and in some cases negative extrinsic value, which he considers to be a measure indicating the put is on sale.

In almost every situation with options, any option that is in the money has a price based on its intrinsic value, the amount that it is in the money, plus the time value, or extrinsic value accounting for potential risk and growth in value over time. But there are exceptions, where the buyer can buy an option in the money for less than the amount that the stock is in the money. This trade, as it turns out, can experience it on both sides of the trade, both with the long, which is generally a good thing, and on occasion on the short side, which can be a big nuisance to manage. That’s the first mind-bender of this trade, which will be explained in detail, but far from the only one. So, put on your thinking cap and get ready to delve into a part of the option world that is rarely discussed.

Diagonal Spreads

This trade is a diagonal spread. The two options expire at different times and are at different strikes. Spreads with the same expiration and different strikes are vertical spreads, and spreads with the same strike prices but different expiration dates are calendar or horizontal spreads. So, a diagonal spread is a combination of calendar and vertical elements.

What is the point of this, you may ask? Well, long duration options generally decay slower than short duration options. So, if we sell a short duration option, while buying a long duration option, we expect the option we sold or shorted to decay faster than the option we bought or hold long. Excluding all other impacts, time should make this a winner for us. But of course, we can’t exclude all other impacts which is why we need to understand the ways the trade can go against us and what we can do about it.

If a little difference in expiration can help with time decay, this trade says, “let’s take it to the extreme!” Let’s sell a put that is a day or two away from expiration, and buy the longest dated option on the table, 5+ years until expiration. Our short option (that we sell) has a very short duration, and the long option (that we buy) has a very long duration. So, we have a very short short option and a very long long option, my very clever explanation that is probably more confusing than illuminating to most of you, but hopefully you get the difference in the duplicated use of the words short and long.

Diagonal Puts vs Diagonal Calls

A more well-known diagonal trade is one that many describe as the “Poor Man’s Covered Call,” which is written about elsewhere on this site. This trade typically buys a deep in the money call with a long duration as a substitute for stock, and then creates income by selling out of the money calls against it with shorter duration. It’s like a covered call, but the trader only pays a fraction of the cost of stock, thereby making it a “poor man’s” covered call.

One issue I’ve always had with the poor man’s covered call, and covered calls in general is that I’ve found the short call being sold isn’t a high percentage winner, in fact, in the majority of cases I’ve studied, the call loses more than it gains, because the stock goes up more than the premium collected, so while I like the idea of collecting premium against a long stock or long option, it just isn’t as good as percentages would predict. Additionally, skew impacts the poor man’s diagonal version by having significantly higher implied volatility on the lower strike long call than the higher strike short call, so there is less premium to sell and more premium to buy.

What if we turn the tables, and use puts instead of calls? What if we trade a poor man’s covered put? Just the concept of this takes some time to grasp. For this trade, we start by buying a deep in the money put, a bearish bet that the market will go down in most situations. We are also buying it over 5 years out. Wait, you ask, do I really think the market will be lower 5 years from now? Should I actually buy a put? Aren’t buying puts the worst probability option trade there is? All good questions, and you’d be right to ask them, except that we don’t plan to hold this option to expiration, and we aren’t buying this to be bearish. We are buying this as a hedge to protect us when we sell a put. We’ll tackle all the negative points of buying a put as we dig deeper into managing the trade.

If we sell a put naked, we are exposed to all kinds of risks, virtually unlimited risk. But, with the purchase of another put with more duration, we limit our risk substantially. We don’t eliminate risk, as we’ll discuss later, but we limit it.

The money maker of this trade is selling the put. As we’ve discussed other places on the site, selling puts is a high probability trade. It is a strategy that typically does better than probabilities would predict. But it comes with tail risk that needs to be accounted for. That’s what the long put is purchased for, to protect the downside. The details are in the Greeks and in the management of the trade. Let’s get to it.

The Initial Setup

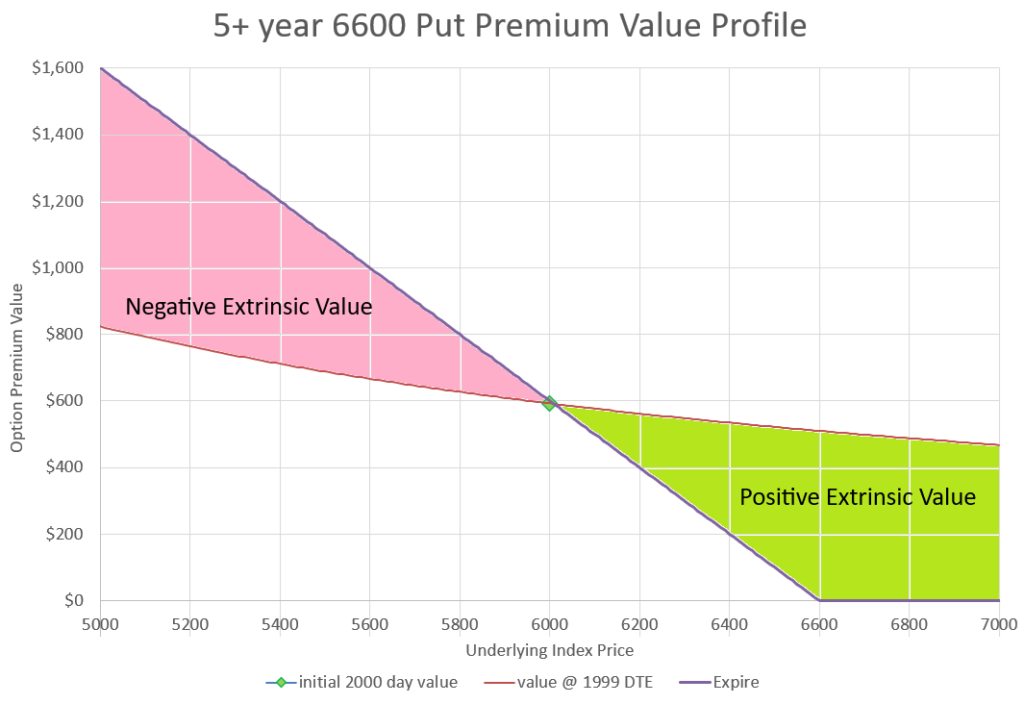

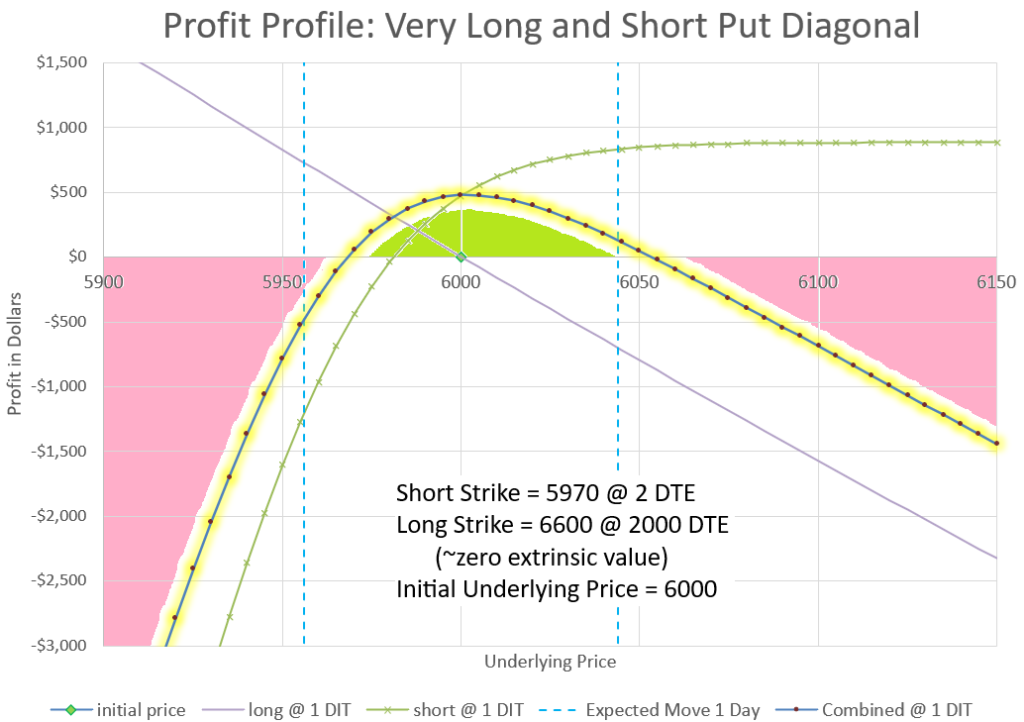

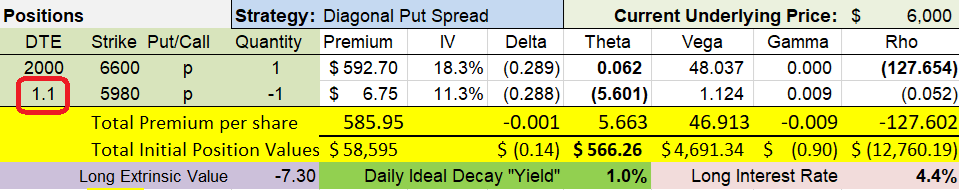

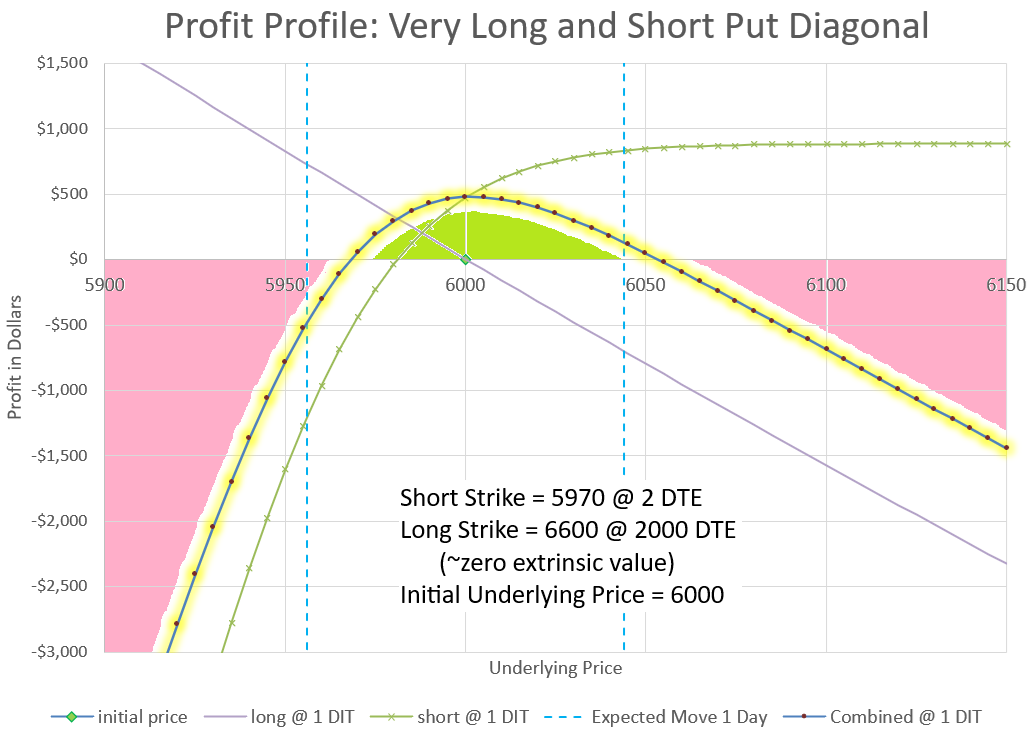

Let’s look at an example of this trade, looking at all the key stats of each of the two options that make up this trade. Here’s a trade set up for options on SPX, the S&P 500 Index, with the index trading at $6000. We will buy a 6600 put expiring in 2000 days (about 5 1/2 years away) and we will sell a 5970 put expiring in 2 days. We’ll talk about why these choices as we go.

The first thing that probably jumps out is that this is an expensive trade, you need almost $60,000 to open and maintain this trade, and that is for one contract. So, if that eliminates this as a choice for you, there are some ways to do this differently that cost less, all with trade-offs. Probably the simplest is to use SPY, the ETF, for 1/10th the cost, but there is assignment risk and dividend issues to be concerned with. You can use less expensive long strikes, either with lower Delta or shorter duration, which we will discuss in much more detail. So, don’t let the high price tag scare you away just yet- see how this trade works and why, then decide if there is another set up that you prefer.

Negative Extrinsic Value

This trade has lots of almost bizarre elements to it to absorb from the stats in the setup table. Let’s start with extrinsic value. The long 6600 put is $600 in the money, but it is selling for $592.70, less than its intrinsic value. How is this possible? There are a couple of explanations that contribute to this situation.

First, think about the fact that while the option’s strike price is 10% higher than the current price of the index, it is dated over 5 years in the future. What are the chances that 5 years in the future the 6600 put will still be in the money? Here’s a clue- the Delta of the option is 0.289, so the market says there is a 28.9% chance that the index will be below 6600, so buying this option and holding it for 5 years would mean a buyer expects the index to actually be below 6000 in 5 years. The market has to not move more than $7 up for this to be profitable at expiration. I don’t know about you, but this doesn’t seem like a good purchase if the plan is to hold until expiration. Call it optimistic, but surely the odds of the market going up more than 10% in 5 years are better than 29% probability. So to get someone to buy this, there needs to be a discount.

How much should someone be compensated to carry this option for 5 years? Part of the equation is the cost of money, based on long-term interest rates. For the last decade, and truthfully in most short duration options, interest rates have very little influence on option prices. Interest rates are part of the pricing of options and are in the Black-Scholes pricing model, but when rates were near zero or we are only talking a few days or weeks, interest is negligible. But when we are talking about interest accumulated over five years at 4-5% interest, the cost of money to tie up is substantial. Keeping money in cash over 5 years could earn 20-30%, so in the money puts have a big hurdle to get over.

The interest rate effect is usually so minimal that this is the first time I’ve ever needed to highlight it in a trade. The Greek for the impact of interest rates is Rho, which I’ve included in the table above. Rho represents the impact of a 1% increase in rates, a huge amount for the value of the long option. It also adds some complexity to the trade. Changes in interest rates actually matter in this trade.

With probabilities and interest rates dragging on the value of this trade, it almost seems like the price of the long option is too high, doesn’t it? But remember, the option is deep in the money and eventually the option will expire and settle out at its expiration price. There is no promise that the market will go up and there is always to possibility that the market could go down, or even go down a lot, so buyers have insurance for that possibility and sellers are compensated for that risk. In the end, options are priced based on differences in price, time until expiration, implied volatility, and yes- interest rates. And those factors calculate out to say that this option has -$7 of extrinsic value.

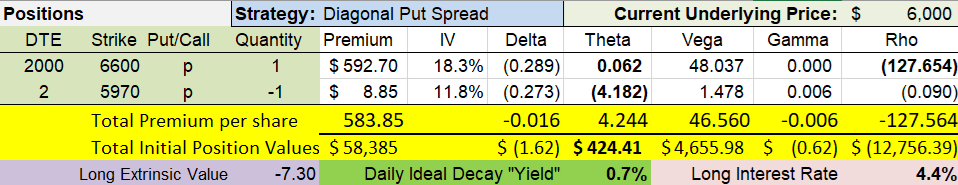

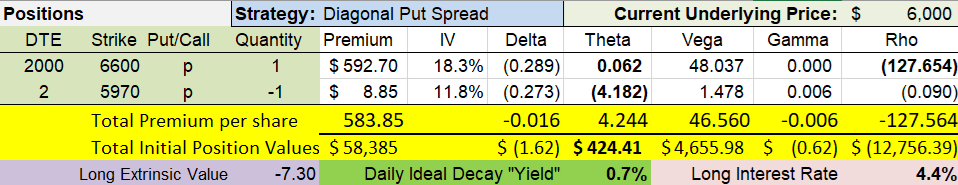

One reason to choose this long strike is to achieve negative extrinsic value. As you can see from the above chart, as prices change on the underlying index, the extrinsic value will change as well, potentially become much more negative or more likely positive if the market goes up. The chart shows the value of the option at different prices at expiration (the intrinsic value) and the premium that the option would currently sell for at varying underlying index prices. The difference is the extrinsic value of the option.

From the table shown earlier, we can see that price isn’t the only thing that impacts the value of the long option. There are two other factors that factor into the day to day changes in option premium- interest rates and implied volatility. Surprisingly (at least I think it is), interest rates play the next biggest role after underlying price movement in the value of the option. The reason is that interest rates can fluctuate up and down in our new environment of higher inflation and higher interest rates. It isn’t unusual for rates to move by 10 basis points or 0.10% up or down in a day. Looking at the value of Rho in the table, that would mean a $12 premium move or $1200, often more impactful than price moves in the underlying.

One would think that implied volatility would drive the premium value of the long option, as the Vega value is very high as well. The difference is that implied volatility of a 5+ year option doesn’t move that much. Most strikes in this area sit in the mid to high teens in implied volatility. After all, this option is looking 5 years into the future and whatever happens day to day has very little impact on the prospects for the range of movement the option will experience before expiration. Implied volatility does change, but maybe at 1/10 or less of the rate of changes in VIX. So if VIX moves from 25 to 15, the IV of the 5 year long put deep in the money might move from 19 to 18 in the same timeframe. Since the implied volatility doesn’t change that much, the large amount of Vega doesn’t really impact the premium that much.

When we pay almost $600 premium, you might think that there would be a lot of Theta decay. But remember, there is negative extrinsic value, so there is no extrinsic value to decay. In fact, if we get to bigger amounts of negative extrinsic value, we can even have some positive Theta on a long option. That’s a bit of a brain twister to consider.

Finally, notice that the premium curve for our long strike is very different from where the premium will be at expiration. The slope of that curve illustrates the Delta value, showing that at this point in time, the option premium will only change about 30 cents for every dollar in underlying price movement. Notice that the premium curve has very little curve to it, which means there is very little Gamma influence. Delta won’t change much until the underlying price moves a fairly significant amount. This should make sense as long duration dampens both Gamma and Theta.

The long put of this trade is mostly a buy and hold position. I’ve spent a lot of time analyzing it because it will behave in unique ways that most shorter duration options don’t experience. The key value that I’ve only mentioned in passing is the Delta value of just under 0.30. I’ve picked this to match up with the short strike Delta for a position that starts at Delta neutral. But we will see that while the Delta of the long is very stable, the other option in the trade is not.

Short Option Considerations

We will quickly see that the short option, the one that we sell with 2 days until expiration, behaves differently than the long option in almost every way possible. In many ways, that’s on purpose. With expiration just a few days away, we are trying to collect a nice premium, see a bunch of it decay, and do that over and over again, day after day.

Let’s look at the setup data again, this time focusing on the second option, selling a 5970 at 2 DTE.

We are selling an option 30 points out of the money and collecting $8.85 in premium. The Theta value says that we expect to have $4.24 of that premium decay in one day, so almost half should disappear over a 24-hour period. What we will find with this side of the trade is that the key Greeks that drive this option’s premium are Theta and Gamma. Vega and Rho generally don’t matter, there isn’t time for them to do much. Delta will change as Gamma changes, and throughout the day, Delta will drive the option price up and down as the underlying index changes.

If you trade this strategy, you will quickly learn that the amount of premium available each day can vary significantly, based on what is scheduled for each day in the future. If the Fed is making a rate announcement, IV for that day will be increased and there will be a lot of premium for the day of the announcement and the days following. Same for jobs numbers announcement days, inflation announcements, and sometimes other big events that are coming with uncertain outcomes. So, while I said that Vega has little impact, the implied volatility for each day can make a big difference in prices from one expiration day to the next. Vega, the change in implied volatility, on the other hand, doesn’t typically have much impact during the trading day, except at the moment where big scheduled announcements occur. For example, once the Fed finishes its announcement, expirations after that drop in implied volatility for the next several days of expirations. This may impact your choice of which expiration day to be in before or after the announcement, and when to roll out to a later expiration.

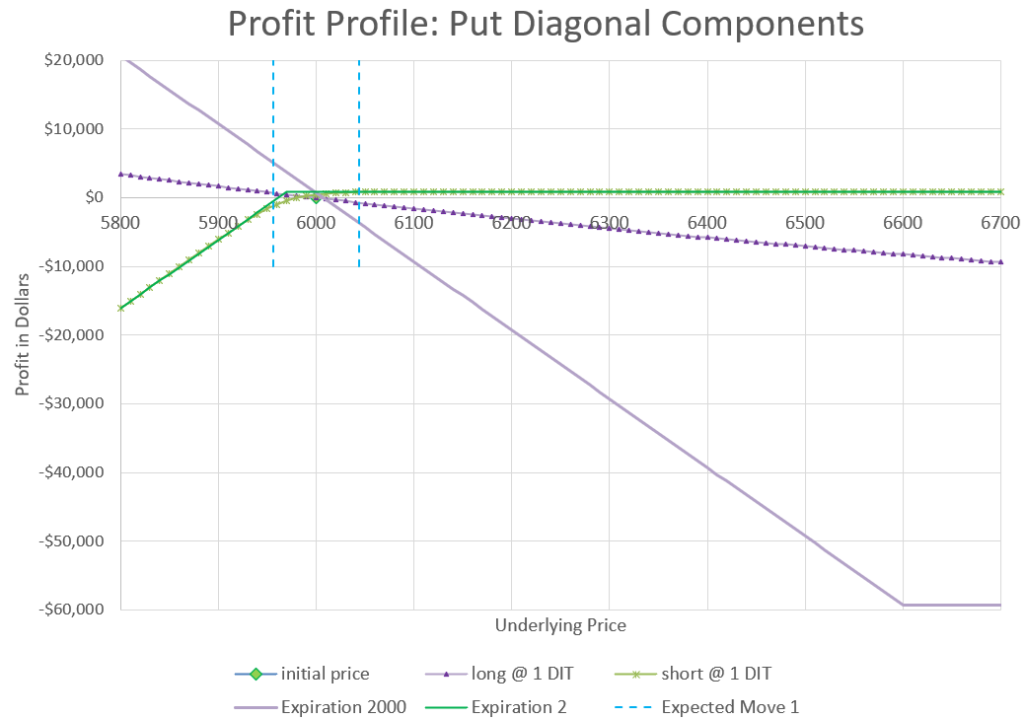

Another thing that is important every day is to understand the valuation curve of the short option and its relationship to the expiration value. While the long option seems to have almost no relation to the expiration value, the short option quickly hugs the expiration value with any significant move up or down in price. Let’s look at a comparison in this chart at prices near the money.

I’ve basically added the short put’s profit profile to the long put’s profit profile, both for a one day move, and at expiration. I’ve also added lines to show what a one day expected move is for the index. What should be clear is that the short put quickly matches the expiration values for about any move outside the expected move. Inside the expected move there are some differences as we are comparing a one day change to a two day change.

If we zoom in far enough and add a line to show the combined profit and loss of the trade after one day, we can start to see the appeal of the trade.

Now we can finally see how the profit and loss of each option combine into a strategy where we expect to profit very often. But, we can also see that moves that are bigger than expected can lead to very big losses. I’ve colored in the profit area in green and the loss area in red/pink. I’ve listed the current price, option strikes and expirations for reference, and again showed the expected move.

Next, we’ll discuss the basic mechanics of managing the trade, both on good days and on bad and very bad.

Basic Trade Management Day to Day

Because the long put is so far out in time and so far in the money, it requires almost no attention, even though its value fluctuates with changes in the underlying index, as well as interest rates. When buying a 5 year option, it can be left alone for a long time.

The action is on the short put of the diagonal. Because it is just a day or two away from expiring, it needs attention almost every day, if not twice a day. There are many choices of variant ways to manage, with trade-offs. Some trade-offs are comfort with a style of trading, while other choices have a big impact on results.

One question people often ask is what time of day should the position be rolled? It isn’t critical on inside days, days where the move is inside the expected move. But, it is good to be consistent, and there is more decay by afternoon than there is in the morning. Because we are rolling before expiration, we have some flexibility to work around other things in our schedule, especially on inside days. On big up days, it may make sense to trade in the morning and again in the afternoon, as we’ll discuss when we get to that scenario.

When I first came across this trade, it struck me as a way to essentially sell a naked put, manage it by rolling, but have a hedge to protect it. After trading this strategy for a while, I find that initial viewpoint holds true. For me, this trade works well for me in every preference I have for trading. For other traders, this trade might go against every instinct they have. So, let’s get to it, starting with the easiest situation to the hardest.

Inside the Expected Move

On the profit chart above, notice the dashed lines of the expected move. This is showing the one day expected move of the index at the Implied Volatility levels that were established when the trade was started. We expect to stay inside these lines 68% of the time. Notice that we have a nice green profitable area mostly inside the expected move. We’d like the market to stay in this area every day, but that won’t happen. However, 2 days out of 3 isn’t bad.

What happens on these green days? Simply said, the short put decays and the long put doesn’t change much. You can see from the profit lines of each option, that small moves cancel each other out between profit and loss of the long and short. We start the trade with premium in the short put that will decay significantly in a 24 hour period if the market stays the same or goes up.

Managing on green days is easy. Just roll out the short put by one day. If we started at 2 DTE, we wait a day until 1 DTE, and roll back out to 2 DTE again. We should be able to collect a nice premium for the roll. So, let’s say we started with $8.85 as in our example at 2 DTE, and market barely moves. Let’s assume our short put is worth $4.00 after a day. For our roll, we buy the 1 DTE for $4 and sell a 2 DTE put for $9.00 to replace it. Let’s also assume that the long put didn’t change in value, so our net profit for one day is $4.85 premium, or $485 for the full contract. And we collected another $500 that we hope to lock in tomorrow. Since I have about $58,000 in capital tied up, my one day return is just over 0.8% on this ideal day.

Which option should we roll to? The market hasn’t moved much, so our strike price probably won’t move much. For the purpose of this trade, I’m trying to sell a put with approximately 0.30 Delta value. If the market went up a little, I might sell my next put at a slightly higher strike price, and if the market is down, I may need to see a slightly lower strike price. Why 0.30 Delta? Because the long put has a Delta of around -0.30, the combination is then Delta neutral. I’m not trying to predict which way the market will go, I just want my position to be affected as little as possible by moves in the market.

Days Up More Than the Expected Move

Normally, I’m excited and happy when the market goes up a lot. As discussed elsewhere on this site, the market has a normal upward bias, it tends to go up more over time than it goes down, so most strategies need to try to take advantage of that. One would think that since the “money-maker” of the trade is the short put losing value, and the short put loses value when the market goes up, we should make money on big up days. But we don’t. Because this is in reality, a bearish trade. Our long put is bearish and when the market goes up and up, the long put goes down and down.

The problem with big up days is that the short put only has a limited amount of premium to lose or for us to profit from. In our example, we start with $8.85 in premium with 2 DTE. That is all we can make from this contract leg. If the market jumps up 150 points over night, the market might open with our short contract worth $0.10 or $0.05, while our long contract went down in value $50 in premium. That’s a $4200 loss net. Worse yet, there really isn’t any way to get it back quickly. As I write this, I’m reminded of a recent event, the 2024 presidential election, where the market went up 15o points overnight. I had rolled down my short strikes the day before with huge IV and lots of premium in the market. The market was preparing for a long, drawn out vote count that would cause huge problems, but by early morning it was clear that Donald Trump had won the election decisively, relieving the market of all kinds of contentious scenarios. I was not prepared for the big upswing overnight. The move set me back, losing a month of profits in one night.

The good news is that big up days aren’t that frequent in nature, and often come at times that won’t hurt this trade, after a big downturn. We’ll discuss that more in the downturn section, so keep the big up day in mind for that.

How can I say that big up days aren’t frequent? The market is in bull market mode almost 80% of the time, and when it is, it sets new high marks all the time it seems. However, what we tend to see follows an old Wall Street cliche that the market “climbs a wall of worry.” What this means is that usually as the market is steadily climbing there is always an underlying concern that the market is too high and any number of things might turn it around, yet there is also a sense of complacency. The worry keeps the market from going up too fast, while the complacency can lead to big downturns without any notice. Markets crash down, not up. For this trade, a big move of 2-5% can feel like a crash- moves this big in a day or a week are almost always to the downside. The biggest up days are usually the day after the market hits rock bottom and with this trade, we should be ready and waiting for that to occur. Instead, let’s talk about how we deal with day after day of 0.5 to 1.0% gains.

One quick little stat to keep in mind- when the VIX is 19, that equates to an expected move of 1% a day up or down. As VIX goes lower, the expected move comes down as well. If you trade this strategy, you’ll quickly see that premium changes a lot day to day, along with the expected move for the next day or two. Sometimes the market is anticipating a big announcement, earnings from a major company, jobs or inflation data from the government, or interest rate announcements from the Federal Reserve. We will see short duration options have much higher premium anticipating these upcoming events. That’s good for us, because we can collect more before events that have the potential to move the markets a lot. On days when nothing big is expected, there is less premium and we have less of a move to anticipate. When trading this strategy, you’ll quickly learn to watch for these big events and be ready to make a quick roll to get more premium if there is a big move up.

Let’s say a monthly jobs number is viewed favorably by the market. The announcement comes on the first Friday of the month an hour before the market opens. We know the announcement is coming and generally in the hour after the announcement, we can see how the futures market is trending and can anticipate where the regular market will open. If the market is opening up 40-50 points and my strike was 15-20 points out of the money at the close the day before, I can be pretty sure that my short put will open with very little value.

If the market opens way above my short put, my goal is to collect premium and get into a position where I can have premium to decay. So, my standard reaction would be to roll up my strikes in the same expiration as I had to the strike closest to 30 Delta. Some traders may choose to sell a slightly lower Delta in case the opening move is over done so they can avoid be whip-sawed. If the option is still a day out, there’s plenty of time to continue to manage it. Another choice is to go ahead and also roll out in time when rolling up- that way there is no need to roll out later in the day to stay at the target DTE for the short position. There’s pros and cons to what you choose, and I’ve found that each trader will determine a level of comfort with their version of management. The key is to move from a single digit Delta value in the short put to something close to the Delta of the long put, neutralizing price movement for the immediate future.

This is probably a good place to remind traders of the Pattern Day Trader rule, which can be triggered with this type of maneuver. If you execute four or more “day trades” within five business days, you will be flagged as a Pattern Day Trader. A day trade is when you open and close the same position during the same day. Pattern Day Trader status is not a good thing to be identified as. Brokers have no choice on this, it is mandated by FINRA, a government agency in charge of these things and is intended to protect small investors from losing too much money. Any account with this status will have significant limits placed on the types of trades that can be done if the balance in the account is less than $25,000. You may wonder why I’m bringing this up for a strategy that requires $60,000 to do. The issue is that many traders may decide to do a similar trade that takes much less capital- we’ll discuss some alternatives before we are done with this. But the point is that if you start rolling in the morning and then roll again in the afternoon, that’s a day trade. If you do it four out of five days, you are tagged a Pattern Day Trader for that account, and brokers and regulators make it very hard to get untagged.

If a day trade is such a negative thing, why consider it? Well, with this trade, notice that the profit curve of the short put goes flat at price movements beyond the expected move while the long just keeps losing. The only way I know to combat this is to roll up the short as much and as often as is needed to keep adding premium to decay. One way to avoid some of this is to consider alternative short DTEs.

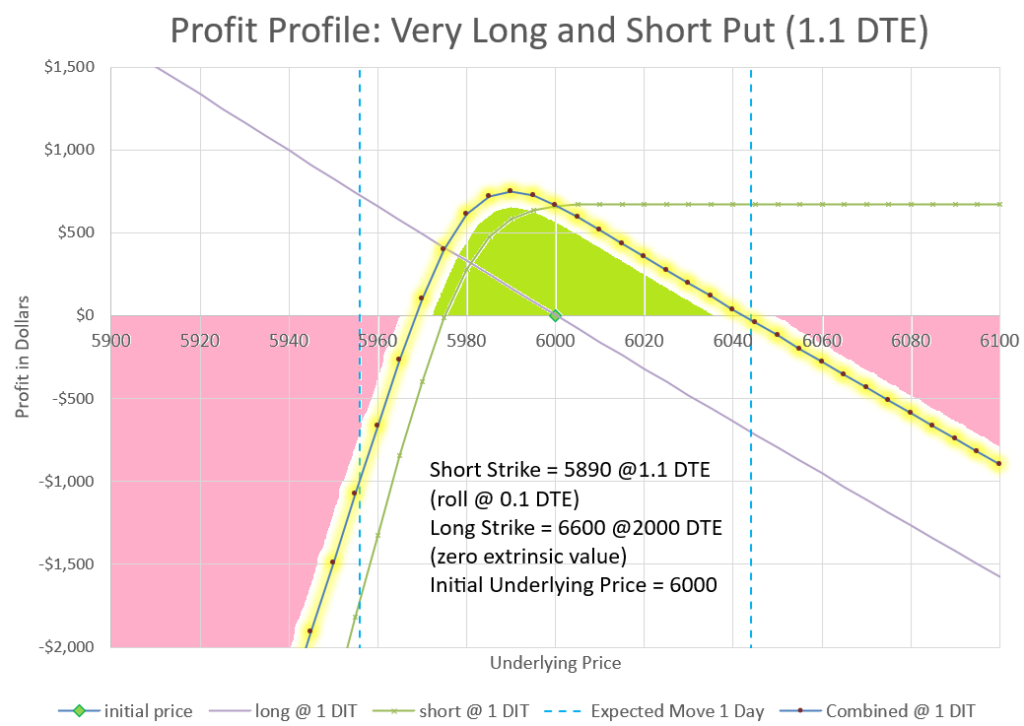

Notice that I have chosen 2 DTE. You may wonder why. If we are going to use the very shortest short, we should consider selling at 1 DTE and rolling right before the close just before the option expires. That should be the fastest possible decay, right? To simulate this, I’ll set up a trade with 1.1 DTE remaining with a plan to roll with 0.1 days left, a couple of hours until expiration. This pushes modelling a trade to a limit, because when options are this short, Implied Volatility is much less predictable, so don’t consider this very precise.

To get to 30 Delta on our short strike, I had to move from 5970 (2 DTE) to 5980 (1.1 DTE), so 10 points closer to the underlying price. Our Theta and Gamma have increased, but our premium collected on the short has gone down. But now, when we look at the profit profiles, we see that there is almost no curve left because when we are ready to roll, there is virtually no time/extrinsic value left, even zoomed in.

If you look back and forth between the two charts, you can see that this 1 to 0 DTE has a higher maximum profit, but the profit curve is narrower. This plays out when there are big moves, but really the difference isn’t that much, so many traders I know prefer this shorter short option. I’ve found there to be less urgency to act on the 2 to 1 DTE version on an up move, but again the difference isn’t that much. If we went out another day to go between 2 and 3 days, the curve flattens and spreads even more.

With this 1 to 0 DTE version, notice that the profit for the short side flattens out at 6000, for a strike that was closer to start with. So, much of a move up beyond where we start at 6000 will decay quickly, and we would see that on expiration morning. I don’t have a hard and fast rule (I probably should), but if the premium is below $2.00 in the morning of expiration, then it is time to roll because there just isn’t much left to decay.

If we roll in the morning, should we roll out and up, or just roll up in the same expiration? If we are rolling an option on expiration day, we are guaranteed to need to make a day trade later in the day to roll our newly sold short put into the next day. So, if this is a concern, the prudent thing is to roll to the next day and save the day trade for another time. If you plan to never have less than $25,000 in your account or your account is already flagged for Pattern Day Trading and you have over $25,000, then day trade away. For me, when I’ve managed this trade using 1 and 0 DTE options, I rarely hold my 0 DTE into the afternoon- I would rather get my roll in early, but I know that means I’m often leaving some decay on the table.

The point of all this back and forth on which DTE to use and when to roll is that like all things in option trading, there are pros and cons to using different mechanics. Each trader can find their own way to manage these positions, but the key is to understand what advantages and disadvantages the choices made have compared to alternative mechanics.

I’ve traded the short side of this trade several different ways to see how each way works out from a number of factors including profit, risk, stress, and timing. Slightly longer duration is easier, but less profitable, which is probably a common theme for most every trade discussed on this site, especially when you read the comments of readers who seem to always want the shortest duration and can’t understand why that isn’t what I have shared.

What kind of profit can this trade make? What I’ve found is that in generally up trending to flat markets, I can make around $600 net profit per week per contract trading between 2 and 1 DTE, and make around $700 per week per contract trading between 1 and 0 DTE. These are averages over months of trades, considering both the long and the short side of the trade. The long side loses, but the short side gains more. Some days and weeks hit close to the maximum, but some days and weeks are losers.

However, when the market goes down, profits essentially stop, and management gets more challenging. It can be a little challenging when the market is down for a few days, or it can be very challenging when the market goes down a lot for a long time. We’ll dig into these scenarios next.

Down moves slightly in the money

If we start at any point in this rolling trade with our strikes sitting at our ideal 30 Deltas and we have a move down outside the expected move, that means our short strike will end up in the money with a Delta of over 50. Theoretically, this should happen 30% of the time-remember that Delta serves as a probability among other things. So, this is going to happen on a regular basis.

The good news is that sense we are treating this short strike like a naked put, we should be able to roll out for a credit. In many cases, we should be able to roll down and out for a credit. So, my goal in this situation is to roll down as far as I can for a credit to get my Delta down to as close to 30 as possible. If I don’t get to roll down much or at all, that’s okay, I’m just trying to bide time until the market comes back, and collect what I can. Remember that when the short side loses, the long side is gaining, so even though the value of the short put may start climbing, the long put is also climbing. To be fair, the short will quickly start losing more than the long is gaining, and that can be painful, especially if this happens when the trade is first opened or when adding an additional contract.

Generally, this continues to be fairly easy to manage, rolling out, or rolling down and out each day while the underlying is within 1-2% of the short strike price or 60-120 points in our example trade. I find it easier to make rolls earlier in the day rather than waiting to the end, but it isn’t a huge difference. The further in the money, the more challenging to roll down and out for credit, and eventually it can be challenging to just roll out for credit if we get too deep in the money with our short.

Moves deep into the money

You’ve probably heard it said, and you may have even read it on this site somewhere that you can always roll out a short option in time at the same strike for a credit. Here is an exception to this “rule.” This exception is a bit difficult to comprehend and will force us to choose between a few less-than-optimal ways of managing the trade when this occurs.

The problem is the issue of negative extrinsic/time value. I mentioned this earlier and explained how this was very cool to be able to buy 5 year puts for less than their intrinsic value. That can be nice if you are buying, but not if you are selling. And this situation occurs with deep in the money puts. It’s always there, but it gets worse when the market is down and Implied Volatility rises. At that point you may find that a put $200 in the money with 2 DTE is priced at $196 or so, and a 1 DTE strike is $198. Remember, at expiration all index options have to settle for cash, so the price for an expiring option 200 points in the money has to be $200. What gives?

When the market has taken a big drop, there is some anticipation of a rebound, so option buyers don’t want to pay full intrinsic value for a deep in the money option, even one that is expiring in the next day or two. Additionally, as the options get deeper in the money with short duration, trading volume is lower, and bid/ask spreads grow, making good fills hard to find. It’s just a bad combination. This situation should occur less than 20% of the time, but when it does, there has to be a plan.

So, what to do? I’ll present two choices, roll down for a debit, or go further out in time to get a credit. Both choices have significant downsides, but there is a silver lining in each. The long-term view is to realize that eventually the long strike that is only gaining 30 cents for every dollar the index goes down will have to be cash settled as well, so if a trader is patient and can avoid paying too much debit on the short side, eventually the money will come back. But let’s hope we don’t have to wait for 5 years for that, and in most cases we are looking at weeks or a few months of tough rolls until we are back in profit mode. Let’s look at how each choice helps us get our short losses back, and you can decide for yourself which strategy is best.

I should probably mention a third choice-one that many would consider a first choice- fold the whole position. Because the long put is interest rate sensitive, there is the dynamic that when stocks fall, bonds often go up lowering interest rates. If this happens significantly, there is the possibility that the long may gain as much value as the short, which could provide the opportunity to get out with a profit even though the short put went deep in the money. Even if the long doesn’t gain nearly as much as the short side loses, many traders may decide that the prudent thing to do is close out and avoid the two choices I’m going to detail out. After all, the market may stay down for a long time, and as you’ll see, fighting to get to a position to make everything back on the someday upswing may be more effort than many want to take on. There’s nothing wrong with folding a position and looking for a better opportunity.

For traders that are up for a fight with this position, I present two competing choices of reasoning. One concept is that rolling down, even for a debit moves the short position closer to getting out of the money and more quickly gets the short to strikes that can collect and roll premium every day to make up those debits. Since we don’t know how long it will take for the market to recover, getting our strikes at least close to the money can allow us to roll for credits that actually have daily decay. So, pay to re-position and then start making money again.

Another concept is that the goal with the short side is to always collect money from a roll, and that eventually all that premium on the short side from being in the money will be eliminated when the market comes back. Earlier, I said that markets don’t crash up. The only exception is when the market bottoms out and comes roaring back up. It’s virtually impossible to predict when a correction or bear market will end, but one characteristic of down markets is violent moves both down and UP! One of the worst moves would be to be positioned out of the money on the day the market jumps up 2-3% overnight because of some event that shows the worst is over. As we’ve discussed, when the short put of this trade is out of the money it has a limited amount of premium to contribute as profit, while the long side has almost unlimited amounts of capital to lose in a short period. Chasing the market down with this diagonal style position could end up a big loss going down, but a bigger loss coming back up. By finding ways to collect premium while the short is deep in the money, a trader will not get whipsawed at the bottom- all that premium sitting in the deep in the money short put can be gained back, eventually.

There’s pros and cons to each choice, so we’ll talk through the mechanics of each. There’s no right or wrong answer, just choices that are quite imperfect.

Rolling Down for a Debit

This is actually the easier choice to understand. It’s pretty simple. Every day that your position is in the money, roll out to the next day and roll down your strike 10 points. That’s 50 points in a week or just under 1% at current SPX pricing of approximately 6000. Most days this will cost around $10 debit, some days a little more, some days less, mostly depending on the market and how it impacts very short term Implied Volatility. Depending on how far down the market is, this may take a while to get the short strikes down to the current price.

You may find on big up days or days when an announcement is coming that you can roll down more than 10 points for a credit, if that’s possible, take advantage. The goal is to steadily get the short strikes down to the current price of the index.

Once the short strikes are close to price of the index, we can go back to managing like normal. If all goes well, the short position can be ridden up and down with the market.

With market volatility high and prices down, my preference is to avoid getting very far out of the money, so I don’t mind being in the 40-60 Delta range in a down market. I wouldn’t pay a debit to get below 60 Delta. Remember that there is a possibility of a big upswing at any time and one has to be ready to aggressively roll up in that case, like we’ve already discussed.

So to summarize, the mechanics are to steadily roll down strikes, paying what is needed to get the short strike close to current prices. We don’t want to overshoot down. We have to always be prepared on the other hand, to aggressively defend any up moves. The difference is that on down moves, our premium serves as a big buffer for moves back up until we get close to the current price. When we have no premium buffer, we have to generate premium.

Finding a Credit to Keep Collecting

Ideally, we would like to just roll out each day and collect a little premium until the market brings the underlying price back up to our strike price. When we are less than 100 points in the money, this is usually fairly easy to do. But as we get deeper in the money, we start running into the nasty impact of negative extrinsic value. When this happens, the premium of a day longer option at the same strike is actually less expensive than the one we already own. So, rolling out would require a debit. This isn’t something we want to do day after day, as it is a losing proposition and the whole goal was to make money off of the short side of this diagonal position.

To give a sense of how this plays out, here is a snapshot of the data from actual option prices of puts at different DTE and different strike prices.

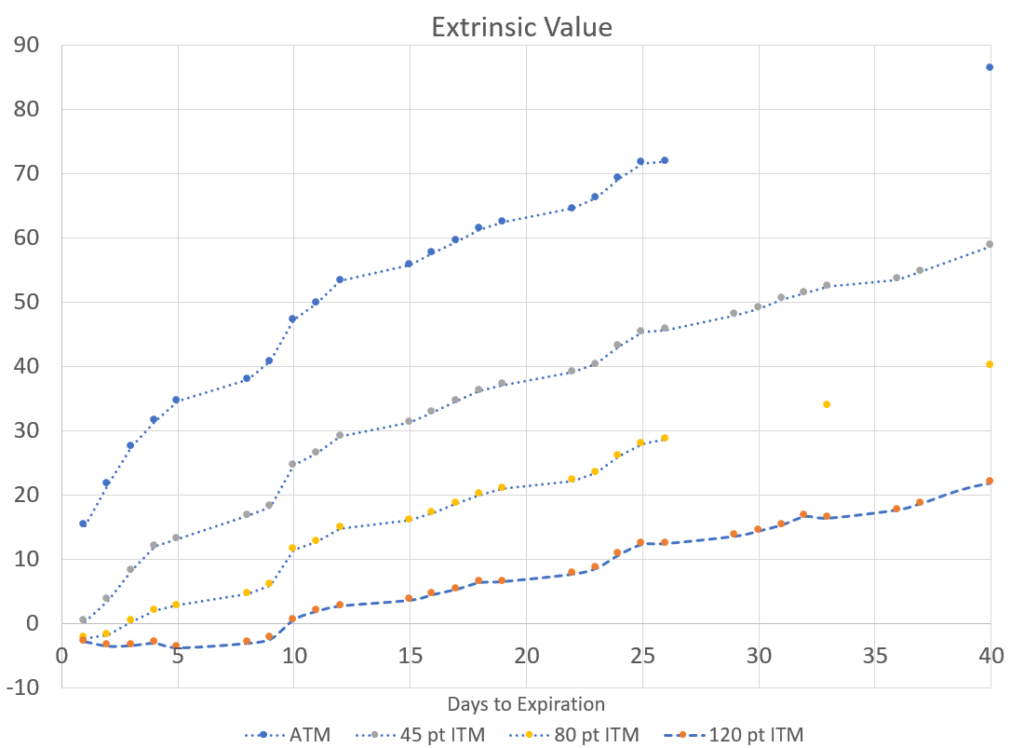

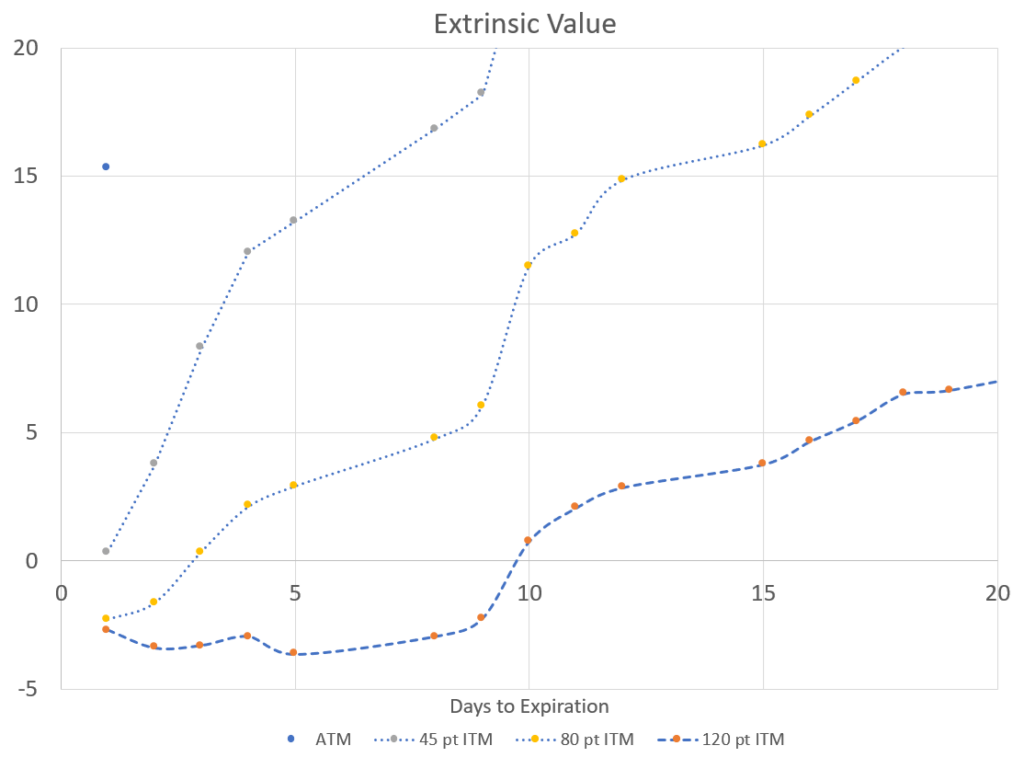

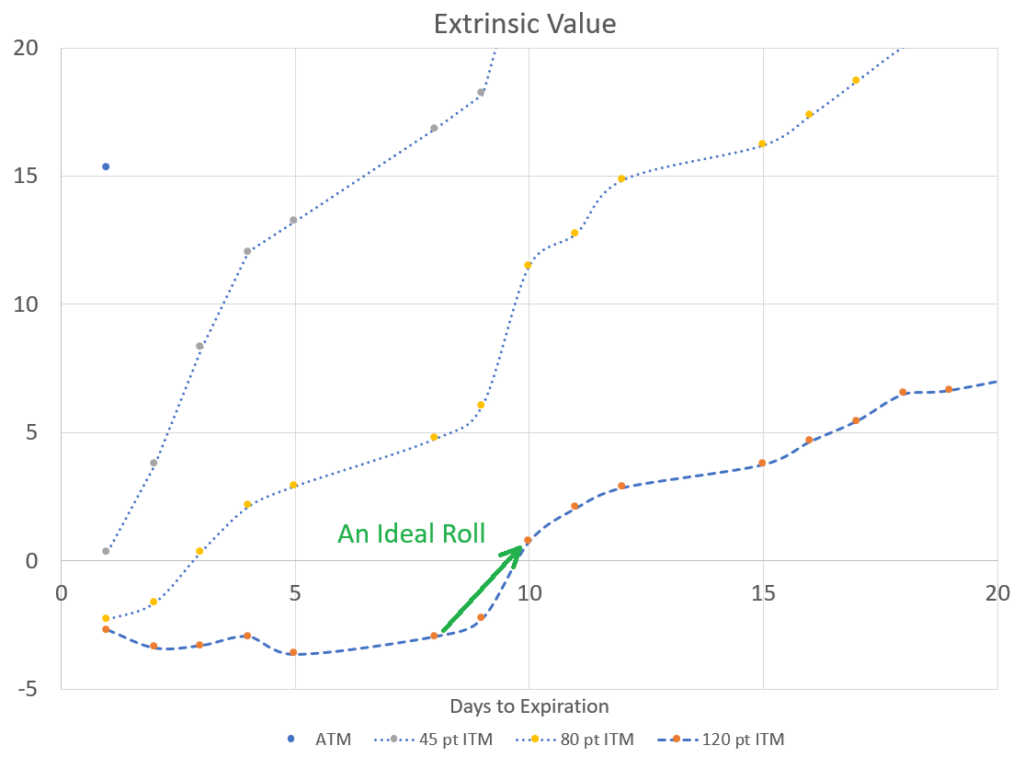

Notice that strikes at the money and a little in the money still have positive extrinsic value at all expirations, but once the strikes are 80 points in the money we start to see some negative values. Let’s zoom in for a closer look:

The further the strike is in the money, the more negative the values are, and the longer they stay negative. However, the situation we want to avoid is to hold from a negative value to a less negative value, so in this example if we sold the 5 DTE version of the 120 ITM strike and held a few days, we lose money. However, if we sold the 10 DTE strike and held until 5 DTE, we’d see decay that would be a profit for this short put.

We can see that the 80 point ITM put bottoms out at 1 DTE, while the 120 point ITM put bottoms out at 5 DTE. The deeper we go in the money the later the bottom point is for negative extrinsic value.

If you are still with me, our plan is going to be to roll our position to the earliest date that we can find our current strike with some positive extrinsic value, no matter how little. Then we will wait for extrinsic value to go negative and then roll back out to a positive extrinsic value. Doing this, we can collect a credit for the roll.

The goal is to roll out in time, collecting premium with each roll and avoiding being in the time frame where the negative values are starting to move toward zero for expiration. At expiration, the extrinsic value has to settle at zero as the option will be settled at its intrinsic value, no matter how negative the extrinsic value was days before expiration.

When the market is down and moving further down, the negative extrinsic value is amplified, and when the market is moving up, the negative extrinsic value is muted somewhat, so the best chance to roll out and collect a premium is finding a time during the trading day when the market is moving up. This makes this activity more of an art than a science.

The goal of each roll is to collect credit and whenever possible move from negative extrinsic value to positive. We want to avoid getting to days earlier than the point where negative values bottom out. Doing this approach may roll the strikes out days or even several weeks in time. If the market stays down, we just lose the opportunity to collect credit on a daily basis. If the market makes a quick recovery, we could end up with strikes that are a long time from expiration that we will have to wait out.

The advantage of rolling for credit is that we never give up any premium that we have collected. Meanwhile, we know that eventually the long end has to close at its intrinsic value and cover the full amount of the downturn. But how much patience does it take to hold on for perhaps months or even longer. Assuming the market eventually bounces back, we’ll get all the premium back that we’ve ever collected and hadn’t had a chance to bank. We also don’t have to worry that our strikes will get overtaken by a huge up move from the bottom because our strikes are deep in the money far away from that bottom.

Having traded this trying to collect premium while deep in the money, I can tell you that this isn’t an easy task. One possible help is to get an idea of the roll trade you want to make and enter a limit order for the amount you think is reasonable to collect. Set up the order and go on about your day. If it fills, you win. If it doesn’t fill, re-evaluate your trade assumptions and look for perhaps a later expiration for your next roll.

Maybe this chart will help you visualize what we are trying to do. We want to move from a negative extrinsic value strike to a positive one, then wait for our new strike to turn negative and roll again to a positive one.

How do we know whether our strike is negative? Just look at the difference between the strike price and the current index price and compare to the premium for that strike. Then, when rolling, look to roll to a strike with more premium further out in time.

Example: Let’s say I have a short strike of 6000 at 10 DTE and the market is at 5800. I find my strike is priced at $190, which is $10 less than the intrinsic value of $200, so I have $10 negative extrinsic value. A quick look at other expirations for 6000 strikes, and I see that $190 is the lowest value available, so my premium will likely go up as expiration gets closer, which will lose money since I’m short on this put. It’s lost all the value it can unless the market moves. So, I want to trade for something that has a relatively higher price that can decrease. Looking through my choices I find that the 17 DTE 6000 strike is priced at $201, $11 more than my position. If I roll to that strike, I can collect $11 to stay at the same spot and have decay work for me for the next several days.

You may wonder, if I can collect $11 to roll out a week, should I instead roll down 5 or 10 points to get a credit and get a little closer to the current price? The answer is yes. Let’s say I could sell a 5990 strike at 17 DTE for $193, I’d collect $3 and also get closer to the current price. Win-win if I can find it.

If all this makes you head spin, I understand, it was a lot for me to absorb, going through downturns holding this trade. I followed this second approach of trying to keep collecting credit and ended up rolling out a bit farther than I probably needed to because I didn’t really understand the curves of extrinsic value and I was impatient and just wanted to kick the can down the road.

Which approach is better?

I have some trading buddies that also trade this strategy and we’ve compared notes on how we managed large downturns. Our comparisons could be a little flawed as we all were making up rules on the fly (never a good plan), but the traders that rolled down steadily regardless that they needed to pay a debit seem to have done slightly better than fighting to always get credit. So, to me it is just a matter of preference, assuming one knows the pros and cons of the mechanics being selected.

Alternatives- underlyings, different DTE?

Okay, so if you are still with me, you may be asking things like how important is it that this trade be done with SPX? Or can we use a shorter duration long put, or a different duration short put? Can we use strikes with different Deltas? The short answer is you can do whatever you want, this page is just an explanation of one version of this kind of diagonal trade, intentionally extreme to show how many factors can come into play. But let’s briefly look at some of these put diagonal alternatives.

Why SPX? What else can be used?

I’ve chosen SPX options for this trade for several reasons. If you aren’t familiar with SPX as the S&P 500 index, check out my explanation about all the different ways to trade the S&P 500 index. Options on SPX are extremely liquid, have expirations every day, are cash settled, can’t be exercised early, and have relatively low commissions and fees as a percentage of the value of the options being traded. Additionally, the S&P 500 in general is very diversified as an index and has relatively low volatility compared to almost every alternative, with less outsized moves than almost any other underlying.

There are two other indexes that currently have expirations every day, the Nasdaq 100, or NDX, and the Russel 2000, or RUT. There are micro versions of those indexes with daily expirations, but they don’t have a lot of volume and can be very hard to get out of positions at good prices. If daily rolling is what you want to do, these three are probably the best. There are also Futures options on all these indexes. They can be used with a little less capital, using SPAN margin, and can be traded almost around the clock. You pay more for commissions, and liquidity is less in off market hours.

We can do diagonals with virtually any underlying, stocks, ETFs, you name it. But, most currently can only use weekly expirations at most, so no daily rolls. That’s less stress and less trades, so maybe it is a benefit to you.

Individual stocks have higher IV, so more decay to work with. If you can deal with occasional crazy moves, a diagonal on a stock can be very lucrative. I have some trading friends that make this the majority of their trades and do very well.

5 Years, Are You Serious?

For this trade, I picked 5 years for the long put for a couple of reasons. First, it is the most extreme length available, so it has the least amount of decay, along with some unique variables you don’t see in shorter durations, so it is a great study. Second, with the right strikes you can have negative extrinsic value, which in theory is buying at a discount.

I’ve been a part of groups that all decided to trade this trade “their own way.” Just pick a different strike and duration and go. I was skeptical as well, so I’ve tried other things. Here’s what I’ve found.

The further out in time you go, the more expensive the long option is to buy. A two year option is way less expensive than a 5 year option. So, if doing this trade for less is a consideration, less time helps. Tying up less capital also may improve the return on capital. The shorter the duration, the less impact interest rates have on the long premium. Swings in interest rates can really move the premium of five year options. A two year option sees much less impact, and a two month option virtually none at all.

The trade-off is that shorter duration options don’t tend to have negative extrinsic value at Delta values that are favorable to trade. So, if that is important, longer duration is needed. Is negative extrinsic on the long put important? Some people like it, but I could easily argue it is down the list on important features of a successful diagonal trade.

Shorter duration options have more Theta (decay) and more Gamma, meaning the Delta tends to change more over time with price movement in the underlying security. The very long long put can maintain almost constant Delta over a long period of time and price movement.

While very long duration has a lot of Vega, or impact from Implied Volatility changes, the actual Implied Volatility of those options barely change, even when we see VIX change significantly, because VIX is a measure of 30 day Implied Volatility. So, if you trade long puts with less duration, Vega may actually come into play.

Another thing to consider is that with a five year long put, you almost never need to adjust it. Maybe once or twice a year you decide to roll the strike up a bit or out to the next year, but mostly you can just leave it alone. The shorter the duration of the long, the more often it needs to be adjusted, either to stay at the target duration, or to adjust for changes in pricing that have changed how it pairs with the short side. For example, when doing a diagonal with a 60 DTE long, I find I need to adjust as much as four times a month for various reasons. So, for longs with less duration, both sides have to be actively managed.

So, yes, you can trade less duration. I’ve done a write-up of another version of this trade with less duration, the Daily Diagonal Covered Put, that shows what is different and the advantages and disadvantages of lower time in the long side of a diagonal spread.

1, 2, 3, 4 DTE? A few weeks?

Is there magic to the length of the short put in a diagonal? As we’ve already discussed, the shorter the duration, the greater the decay or Theta, but the lower the premium is, so the closer the monitoring of the position needs to be. As I mentioned selling a 1 DTE and rolling back out each day on expiration day before expiration gives the best return on the short side. The challenge is that this means the trader has to deal with this every day, and maybe multiple times in a day and always be alert to not have the market run away to the up side.

With each day extra of duration, you get a little less decay per day, but a little less urgency to manage the trade as closely. And if you are trading a diagonal on a stock or ETF that only has weekly options, you can only trade options that are 7 days apart and you don’t worry so much about each day’s decay, just the watchout to make sure that there is always premium available to decay.

You can change the number of days the short is out in time for a number of reasons. Say you go on vacation or you have a day you know you can’t trade. Just roll out the short side as many days as you need to be away for a bunch of extra premium and hope things stay reasonable while you are away. Or, as we’ve discussed, if you want to collect a credit when the short put goes way in the money, you may have to roll out several days, or even weeks, to keep collecting credit.

The bottom line is that each trader can choose the duration that works best for them, just understand what the implications are of that decision.

Why Delta matters

Here’s maybe the most important point of trading diagonals- the Delta of each side matters more than almost any other factor in setting up and managing the trade. The Delta values of the strikes you pick determine whether the trade is bullish, bearish, or neutral, and by how much. The examples I’ve shown in this write-up have tended to have both sides of the trade with 30 Delta in each direction, making this a mostly neutral trade. You can see that I’ve tended to tweak it slightly to the bullish side, the short has more delta than the long. This is because there is more of a penalty to the upside, in that the lost decay from the short can’t be recovered, than there is on the downside where you can roll and wait to get your lost premium back.

Where I’ve seen people really underperform on this trade is when they’ve looked at the big negative extrinsic value of very deep in the money long puts, puts with 50 Delta or higher. Couple this with a short Delta of 20 or less because the same person wants to avoid having their short get in the money, and you have a very bearish trade that does badly in any kind of uptrend, which is the majority of the time. If you are setting up for a bear market, maybe this will work, but most people I’ve seen do this set up do it without understanding how powerful the impact of Delta is on the performance of the diagonal.

So, this brings up another way that a trader can modify the trade to match their outlook. By intentionally adjusting the Delta values, you can make this setup either bullish or bearish by picking strikes at different levels on either the short or long side. I tend to not try to predict the future, so I’m more inclined to be close to neutral, with perhaps a very slight bullish setup, but to each their own.

If -30/+30 Deltas work, how about -40/+40, -50/+50, or other semi-neutral combos? Sure, I see a lot of people trade these types of strikes, especially if the long put isn’t a very long duration. Maybe someone is trading a diagonal with 1 week on the short end and one month on the long end, so they pick both strikes at the money with about 50 Delta on each put, which if the strikes are the same, it is no longer diagonal, but a calendar trade. On our much longer setup on the long side, higher Deltas mean the position will be in the money more often on the short side, which can be manageable as we’ve discussed. There can be more premium to decay at higher Deltas as well.

A somewhat related issue comes up with lower Deltas when the duration gets less than a few years. To have equal Deltas, the long strike ends up needing to be lower than the short strike, which adds an additional form of risk. Now, instead of a true debit spread, we have a spread that has the risk equal to the width of the spread less the difference in premium. And with every roll you make on the short side, the buying power changes as the spread width changes. For example, if your short is at 5980 for 1 DTE and the long is 5800 for 60 DTE, you need the 180 point difference times 100 or $18,000 buying power in addition to the cost of the long put itself minus the short premium you collect. So, the idea of doing this trade for a lot less capital has some limits that may not be obvious. If you are looking for the sweet spot, that isn’t it.

So, as you plan how you want to set up a trade like this, pay attention to the Delta values as well as buying power requirements for the strikes you end up with. There are lots of combinations that work, but if you ignore Delta, you can end up with some really poor trades that just lose. I’ve known a number of people that ignore this and can’t figure out why this kind of trade rarely works for them, and they just don’t get it.

What kind of results can this deliver?

My experience with this specific version of diagonal is that I tend to average around a 1% gain per week, taking into account the net profit of both sides of the trade compared to the capital required.

I think it is important to pay attention to the performance of both the short and long side of this trade. In most cases, the short will make money while the long loses. If you only watch one side or the other, you can get a very skewed view of how the trade is performing. One trader that I know that was doing a version of this was very proud of how much premium he was making on the short side, but couldn’t understand why his account wasn’t going up. He was trading fairly low Delta shorts that he could roll every day and they were nearly worthless when he rolled, so it looked great. But, on days when the market went up, his longs were losing more money than his shorts were making because he wasn’t aggressively rolling up his shorts when the market went up. He missed that part of the management of the trade and his results showed it. I’m a proponent of logging all trades for ongoing analysis, and I think it is especially true with this type of trade. If you see that the trade isn’t making money when it seems like it should be, it is a prompt to go look at the mechanics of how you are managing the trade day by day, and look at how each side is contributing to the result.

I will add that as I’ve mentioned several times, I’ve chosen this trade partially as an extreme example of a diagonal trade. As such, I can also say that there are better returns on capital, arguably with less overall risk with somewhat lower duration on the long side. However, there is also a higher amount of volatility on a day to day basis on a percentage basis with less duration on the long side. What I’ve seen trading this at different durations is that the gain on both the short and long side is nearly the same with each variation, assuming that the Delta is mostly neutral. The difference is the amount of capital tied up which can also be a bit of a buffer against big percentage moves day to day. Pros and cons for every decision.

Final Thoughts

This is by far the most complicated trade to explain that I have taken on in options. There are a lot of layers of detail that aren’t immediately apparent at first glance. I’ve tried to present the good, the bad and the ugly of this.

In the end, the appeal of this trade to me is that it allows me to simulate being free to sell naked puts at short duration without the true consequences of actually selling naked. This is also a trade that continuously rolls a short option (my favorite way to manage a trade), with lots of protection on the downside, which you can’t get in other trades. Everything else is just a lot of details to enable this. Those many details are all the crazy peculiarities of option trading, kind of summarized like you don’t see in many other option strategies, so it is a great learning opportunity. So for all those reasons, I hope you can understand why I felt compelled to write this and in so much detail. Happy trading!

Updated perspective

After trading this strategy for nine months, I have decided that I really don’t like it as an ongoing strategy. This strategy can be very profitable in slow moving markets, but the management strategies for down markets have turned out to be very difficult to actually do.

While profitable, this trade consumed a huge amount of capital as discussed. All the while trading this strategy, I was testing other strategies that required much less capital and realized there were many down sides to this very long and very short diagonal spread trade.

The problem starts in that in a down market, the short put quickly can get to a Delta of nearly 1.0, while the long put stays firm at -0.30. This leads to significant losses that can be recovered if the market comes back up, but in extended downturns, this is a big problem and there is no guarantee of a quick recovery. Additionally, most brokers will not recognize this the long put as a hedge if the short put gets over 5% in the money, and then categorize it as a naked cash-secured put, requiring over $500,000 in capital, or an expensive debit roll-down of the short strikes to get within 5%. Finally, if the time comes to close this out, the long put is not very liquid and can be hard to fill at a reasonable price, and the short put if deep in the money is also not liquid, so closing on both sides creates a lot of slippage.

My take-away from this trade is that it is very interesting as a concept, but not practical as a real ongoing strategy. Trading this exposes a lot of concepts in options that are very useful for understanding how different factors impact option pricing in the extremes, so it is a great learning tool.

I’ve since migrated to other versions of diagonal trades that can be rolled daily with much shorter durations. By rolling both the short and long side of the diagonal regularly, the diagonal can be kept close to Delta neutral and less susceptible to huge losses from market downturns.

Thank you for taking the time to provide such a thorough analysis of this strategy. I have implemented this strategy in the past with great success, but I encountered challenges with its day-to-day management. I attempted to roll out for credits while trying to keep the same strike as before. However, as you mentioned in your article, you ended up extending the duration during multiple down days. I also appreciate the use of the two-day approach you described, as it offers more flexibility for management.