I’m a big fan of front ratio type trades. I’ve written about my success with Broken Wing Butterflies and Broken Wing Put Condors. Taking this to a new level is the 1-1-2 Put Ratio trade. This is a new level of ratio trade, because it features naked options with a buffer of protection from a debit spread. The idea is a bit complex to grasp at first, and this is a trade only for traders that have a deep tolerance for risk. The trade involves buying one put and selling a total of 3 puts further out of the money to collect a net credit. Theta makes the value decay quickly, and over time, the purchased put can protect the short puts from most market moves.

I’ve written a separate post on the defined risk version of the 1-1-2 trade, the 1-1-2-2 Put Ratio, while the Broken Wing Put Condor, or 1-1-1-1 is a defined risk version of the 1-1-1, another ratio trade that is very similar. I don’t know of a named reference to a bird or insect for this trade, so I’m sticking with 1-1-2, although I’ve heard some liken the profit curve to that of a whale with a big profit hump and long tail.

I picked up the concept of this trade from one of my favorite traders, “Sweet Bobby” Gaines, who I have mentioned previously in at least one other page on this site. Bobby is a big proponent of the 1-1-2 trade, and has posted numerous videos on it on his YouTube channel, including his recent rising star appearance on Tasty Live. But really, these trades are the next level of evolution moving from broken wing butterfly to broken wing condor to “one louder” as they say in the mythical group Spinal Tap.

What all these trades have in common is selling an out of the money debit put spread, and financing by selling further out of the money puts. The combination delivers a net credit, but also sets up an interesting dynamic of extra rapid decay of the premium involved. The farther out puts decay faster than the closer debit spread, and often lead to the debit spread having more value than the farther out of the money put. This trade takes in a credit to open, and can possibly take in a credit to close. At least that’s how I set them up and manage them.

All these trades are a variation of a front ratio spread, where more options are sold than bought with hedges added to define risk. I’ve also written about back ratio spreads where more options are bought than sold. Front ratios are designed for maximizing decay, while back ratios set up multiple long positions paid for by a costly short position. So what is a 1-1-2?

1-1-2 Basic trade setup

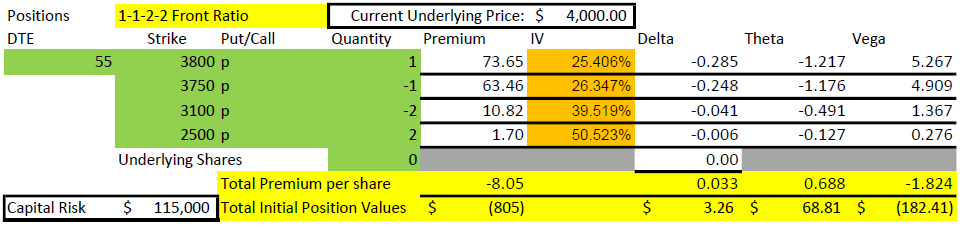

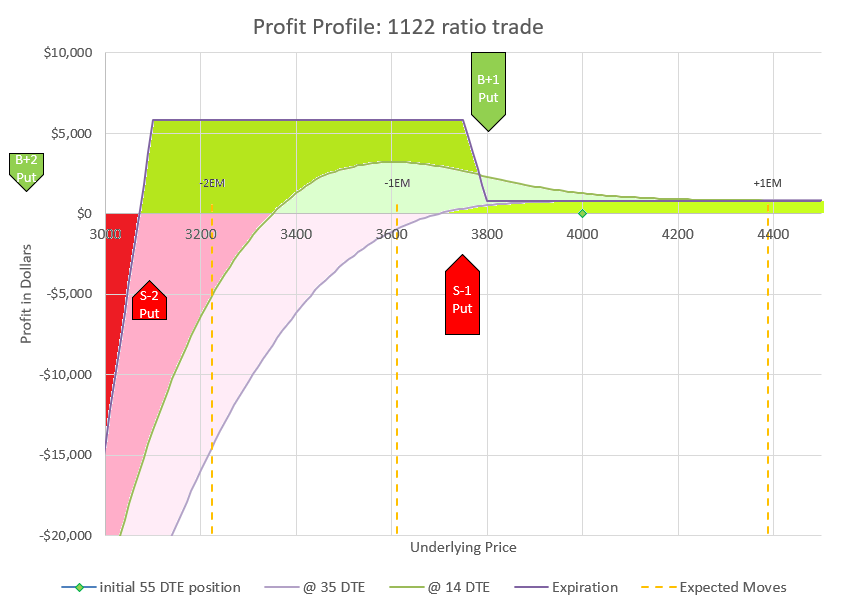

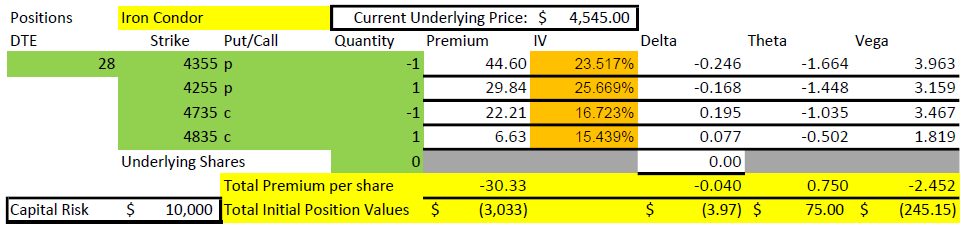

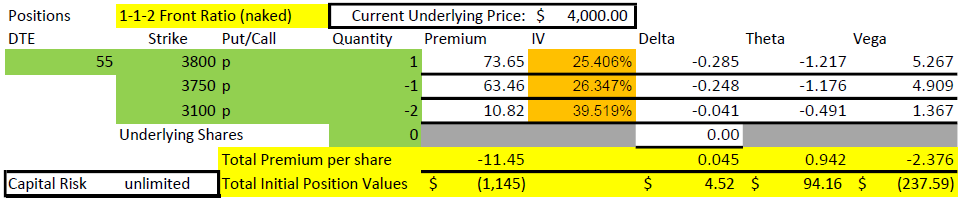

The 1-1-2 takes this a step farther than the broken wing butterly or condor, because we use two puts very far out of the money to pay for the debit spread. The 1-1 part is buying a put around 25 delta and selling a put around 20 delta. The -2 part is selling two puts at around 5 delta. The goal is for the 2 puts to sell for about twice what the 1-1 debit spread cost. I like to set these up with 50-55 days remaining to expiration, quite a bit longer than the other ratio trades I’ve discussed. The added time allows the naked puts to be extremely far out of the money, while still having some meaningful value. I know other traders that go out even farther to over 100 days to get the strike price of the two very far out puts 25-40% below the current underlying price. Like all trades, it’s a matter of personal preference once you know the trade-offs.

What is the advantage of this setup? Well, because each of the two short strikes are further out, we greatly improve the odds of being profitable, and increase the initial rate of decay of the total position. We end up with a big gap between the debit spread strikes and the two short put strikes. Lots of good things happen with this setup. The biggest upside is that there is no upside risk- if price goes up, the trade makes money. The downside of this trade is that it can consume a lot of capital and has significant tail risk, which we will get into before we are done. Let’s look at a typical example.

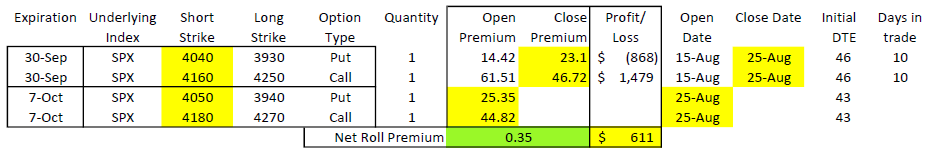

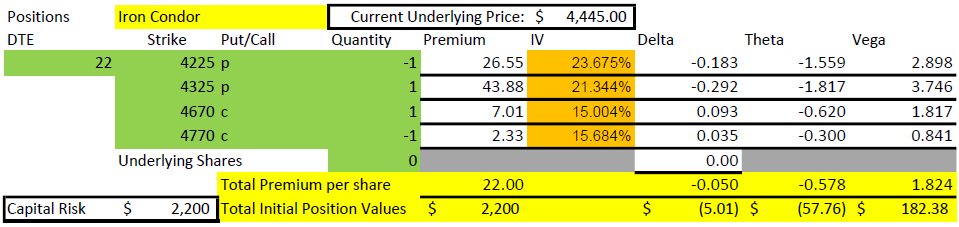

While this table shows the risk as unlimited, it is actually $618,855, the value of two 3100 puts if SPX went to zero by expiration ($620,000) less the $1,145 collected to start the trade.

Some accounts and some brokers require all trades to be defined in their risk. For example, retirement accounts generally aren’t allowed to use option margin and so any naked put would have to be cash secured. That’s why I’ve written the note about the 1-1-2-2 trade which defines risk to just over $100,000 with two even further out of the money long calls (which is still a huge amount). For this 1-1-2 trade, eliminating those two long puts would mean the max loss would go up to $618,855, assuming that SPX went to zero, while we are holding two short 3100 puts. SPX will only go to zero if we see modern society end, and in that case, we’ll probably have bigger problems than our option positions. But rules are rules, and so if you want to trade without the long puts in a retirement account, you would need $620,000 capital to make a likely $800-$1200, or less than 0.2% return in 55 days or less, probably not the best use of capital. We’ll discuss other alternatives after we review the details of the 1-1-2 trade.

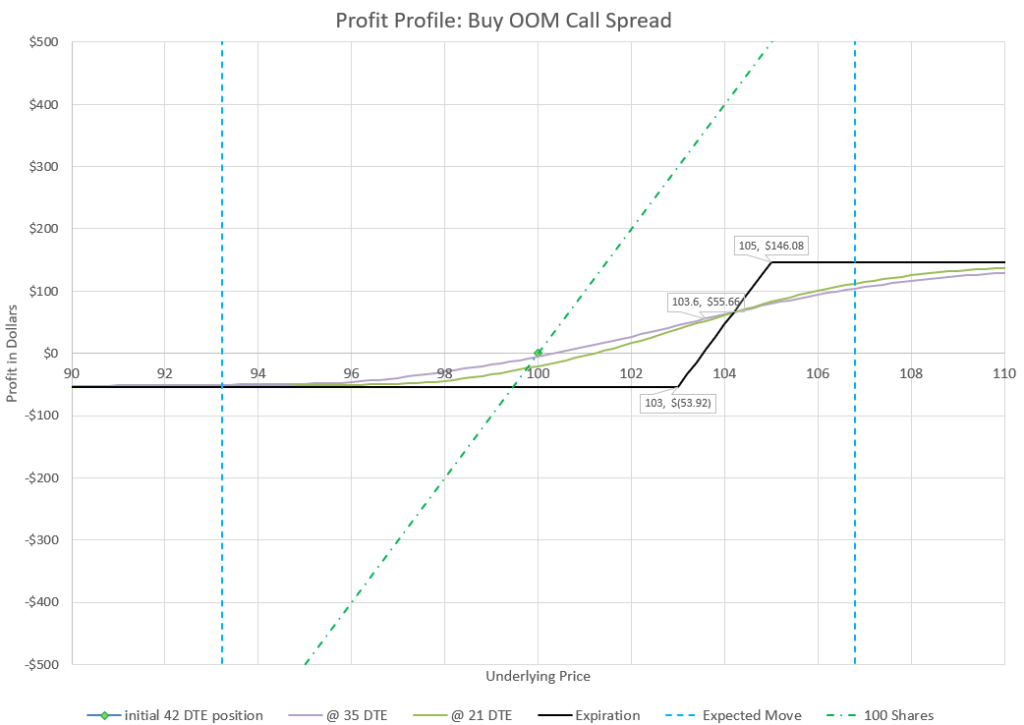

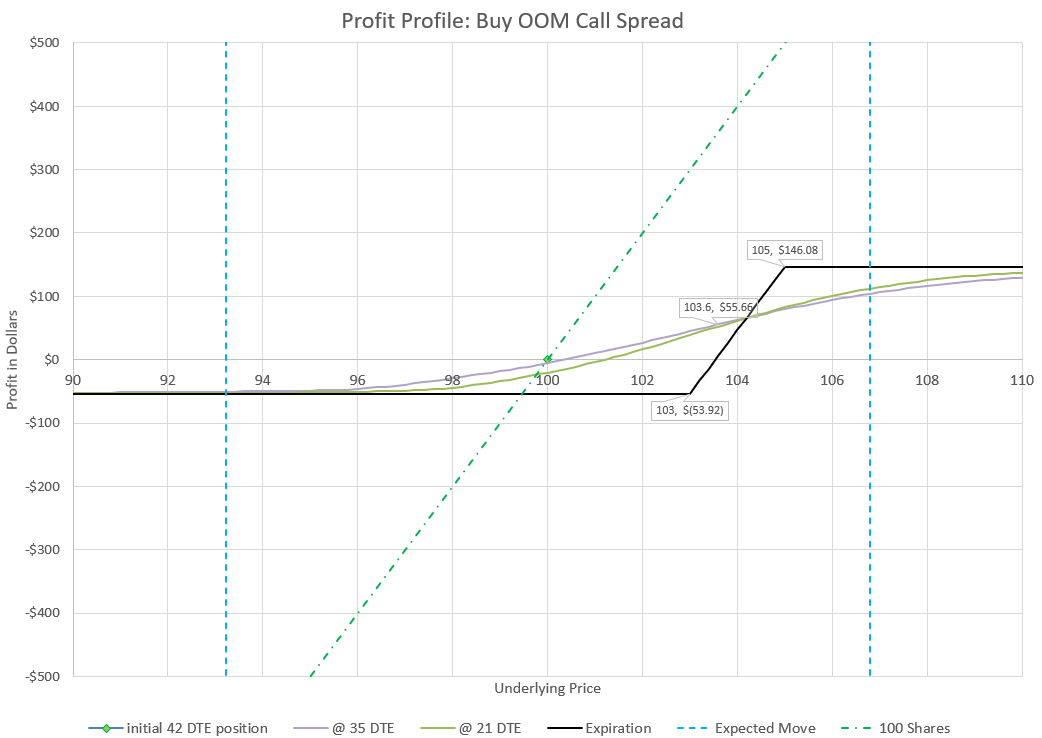

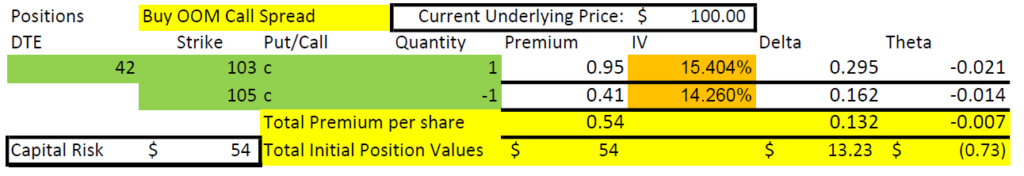

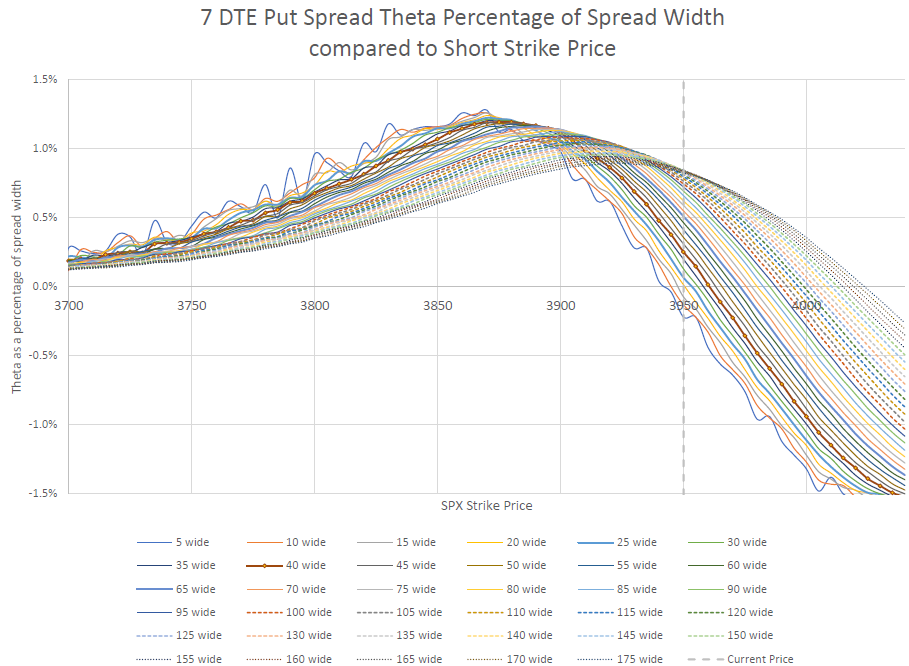

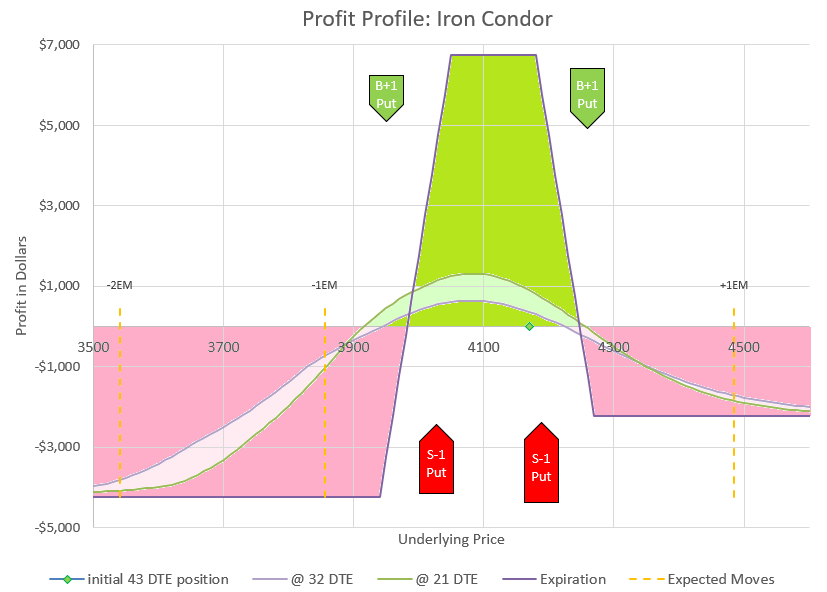

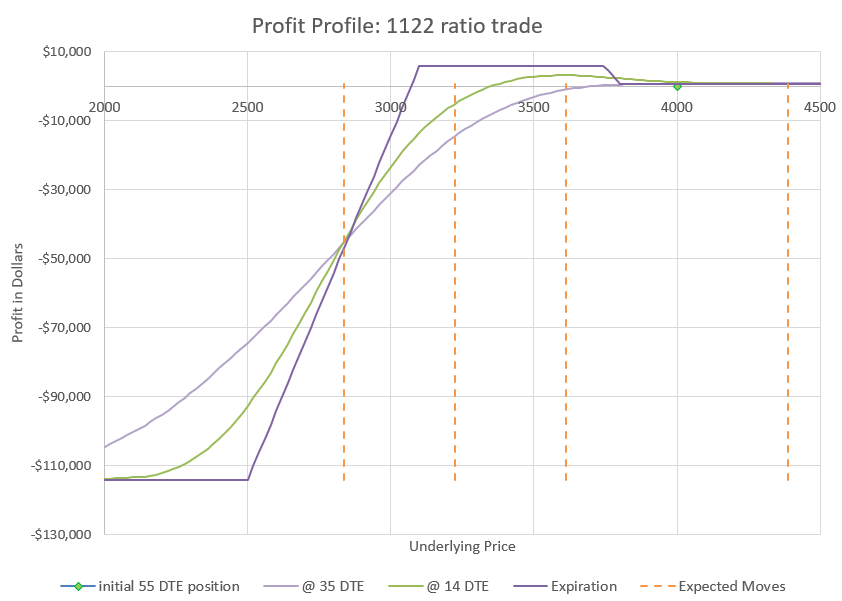

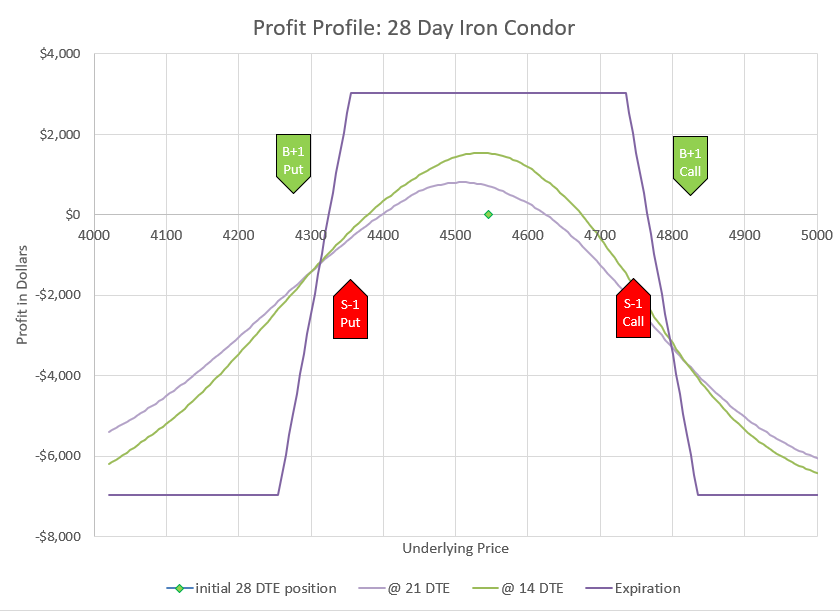

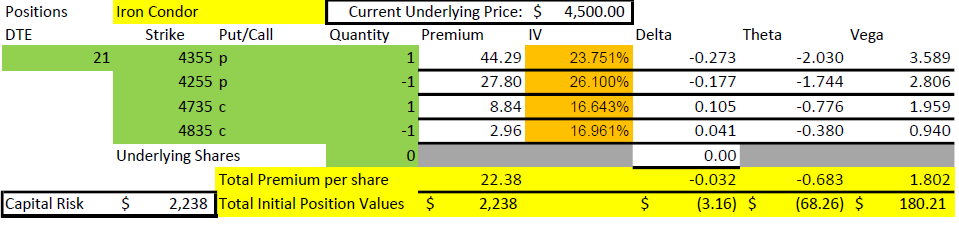

This chart shows how changes in the underlying price will impact the profit and loss of the trade. We evaluate at four points in time. The green diamond shows our initial position at 55 DTE, underlying price is $4000, and the P/L is zero. The curvy lavender line shows how price would likely impact the position with 35 DTE. The green curve shows the likely profit at 14 DTE, and the sharp purple lines are the expiration values. We know exactly what expiration values will be at any price, but the curves are estimates based on likely impact to implied volatility as time passes and prices change.

The first thing I want to point out in this example is that the 3100 short put is 900 points below the current price of $4000. For that strike to get in the money, it would take a 22.5% decline in the market in 55 days. That won’t happen very often. To be fair, this example uses values with VIX at 25, a historically higher than average value, but for the timeframe of 2020-2022, a fairly middle of the road level. The higher that implied volatility is, the farther away the short strikes can be and still collect meaningful premium.

The next thing to point out in the setup numbers is the Greeks. Delta is fairly flat at +4.5. For a credit trade, that isn’t much and means that the position can handle some movement in price. Theta is $94/day, and we collected $1145. So, the position is expected to lose 1/12 of its value each day. But we have 55 days, so how does that work? Quite well, I’d say.

Remember that our starting underlying price is $4000 and the trade is profitable at expiration as long as price is above 3100. The chart above doesn’t show losses all the way down to zero price, but just imagine zero price and -$618,855. Our probability of profit is 96% if held to expiration based on the Delta of 4 for the naked puts.

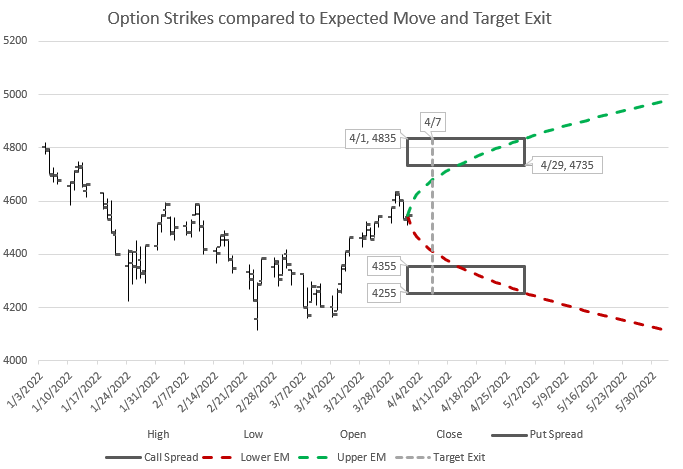

1-1-2 Trade Expected Move Analysis

I’ve put in dotted lines to show the expected move and multiple expected moves down. If you need a refresher, check my earlier post on expected moves. It is likely that price will end up inside of one expected move, the dotted lines on either side of the current price of $4000. There is approximately a 2% chance that price will move two expected moves to the second dotted line below the current price, which would still be max profit for this trade at expiration. And there is approximately a 0.3% chance of moving three expected moves to the far left dotted line. We can go further, but the odds keep dropping as we go to lower levels. However, as history has shown, moves down tend to have somewhat higher probability than theoretical probabilities once we get beyond two expected moves. The point is that this trade is very likely to end up profitable, but there is risk that an extremely big move down could lead to an extremely big loss. We’ll talk about ways to reduce exposure later.

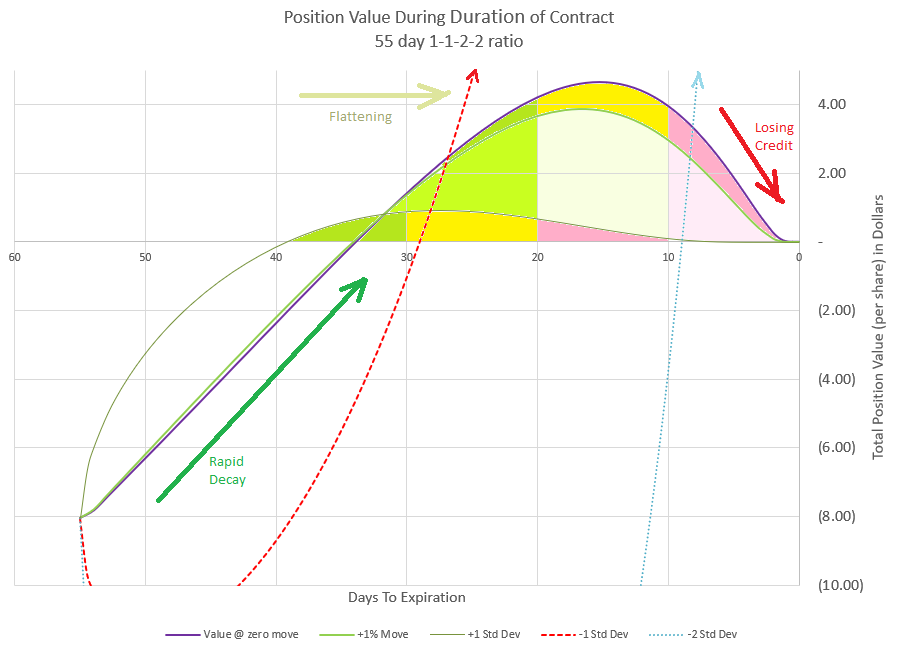

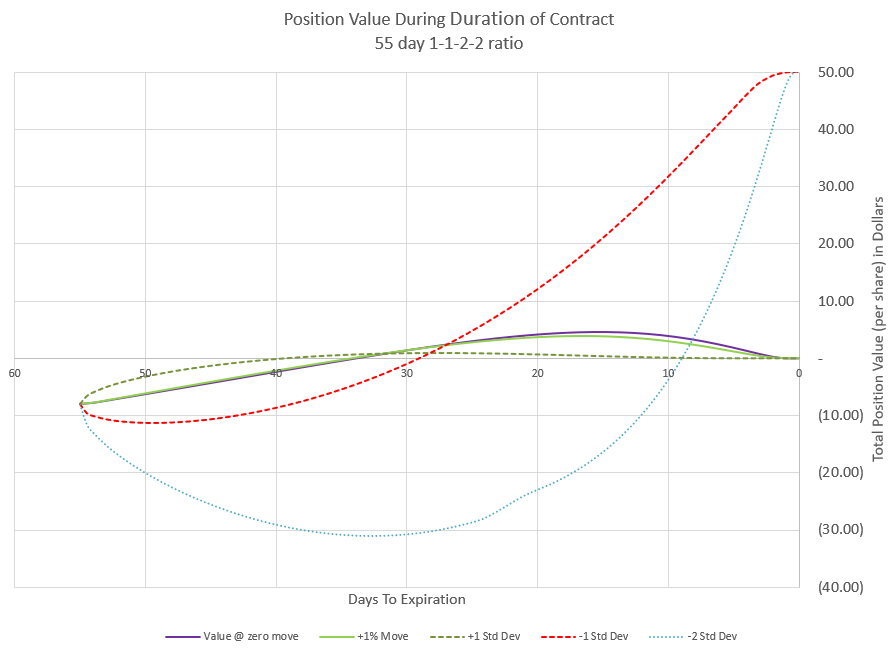

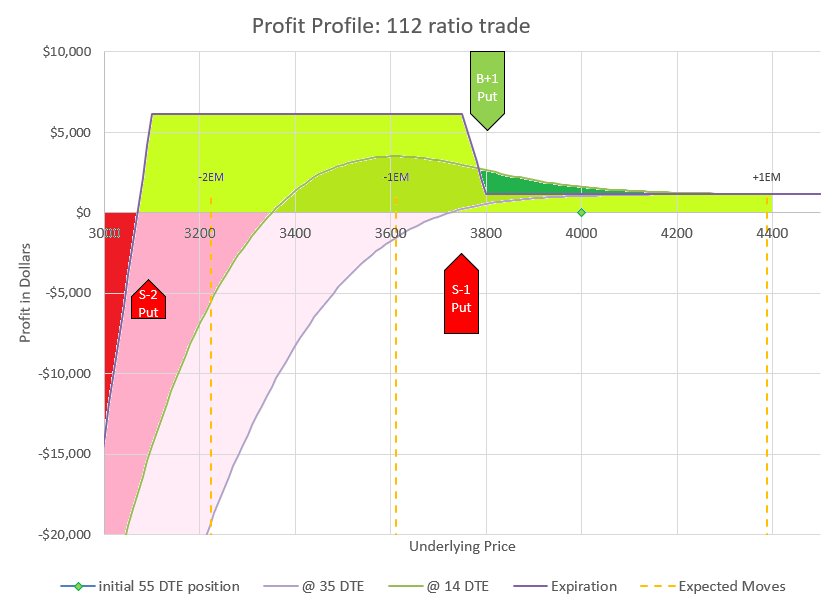

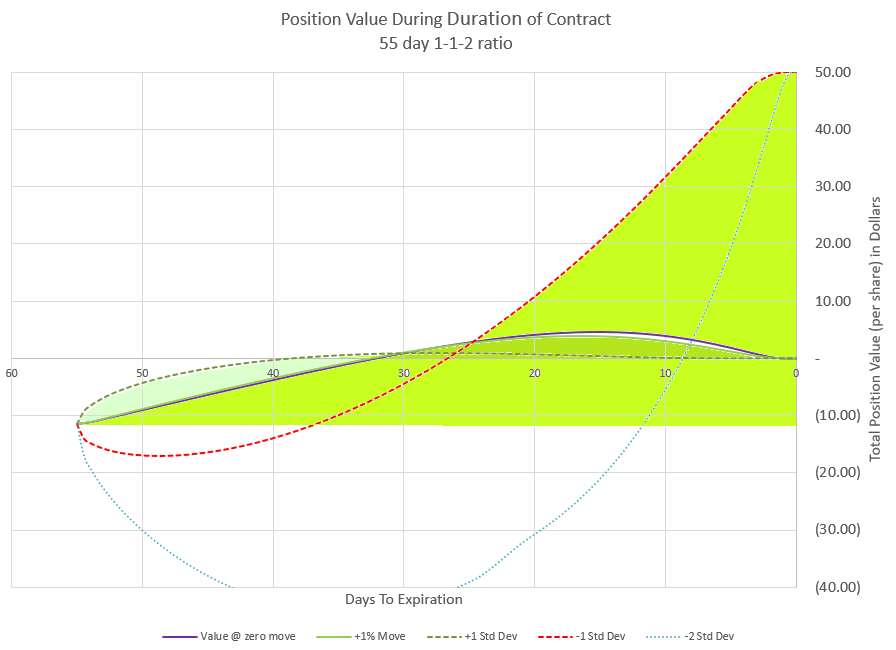

Let’s look at this another way. Prices don’t generally move immediately to a new level, but have probabilities of moves that get bigger over time. Again, going back to expected moves, let’s compare how we might expect price to move during the duration of the trade.

In this chart I’ve shown several outcomes. The zero move is if price doesn’t change at all, a baseline. I’ve shown a +1% move which is in line with the positive drift of the market. There’s also a line for the positive expected move and the negative expected move, where price is likely to be within at any point in time. And finally I’ve shown a curve for a price move of two times the expected move down. Notice where the strikes are relative to the price curves are. The negative curves take time to get below the upper 1-1 put debit spread strikes, and never reach even the short put of the 2 further out short puts. This chart also shows where two even further out long puts would be placed for a 1-1-2-2 version, but that’s covered in the post for that trade. For most people trading this strategy, defining risk with deep out of the money puts doesn’t provide a lot of protection as it is extremely unlikely that those puts would ever be in a position to reduce the level of a loss as this chart clearly shows. So, let’s not dwell on them.

Now let’s look at what happens to the value of our premium if price were to follow each of these curves. This is a view that you don’t see much because it is based on lots of assumptions for the pricing models. Since implied volatility is not predictable in the future, we have to guess how it will change if underlying prices change and how that will in turn impact prices. Based on how price changes have historically impacted implied volatility, we can have a decent estimate of how it will likely change with future price changes. I’ve used a model to take all that into consideration for these position value charts.

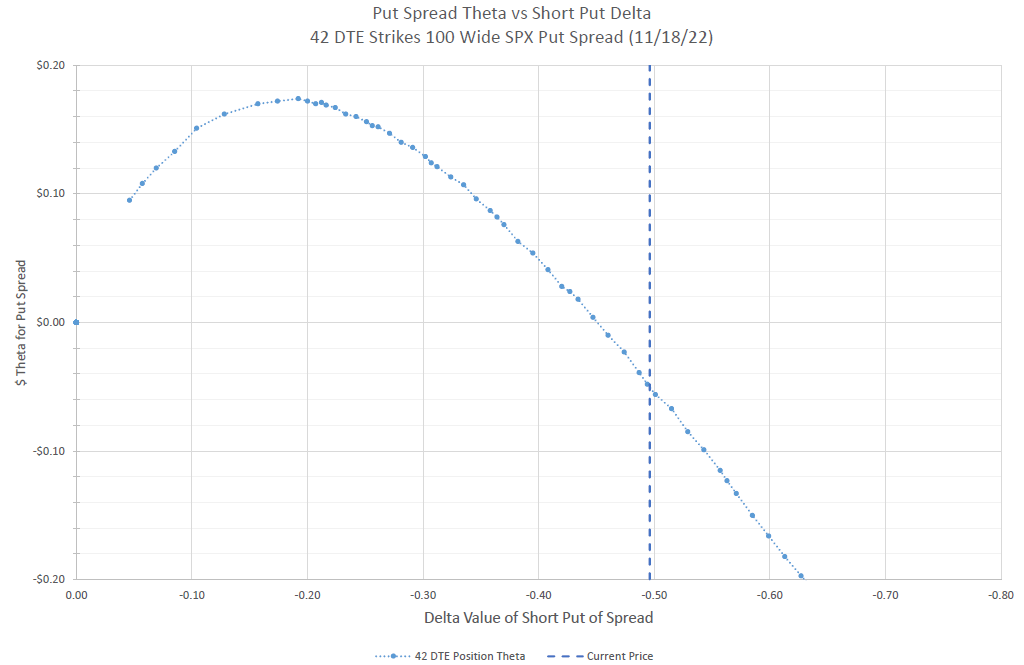

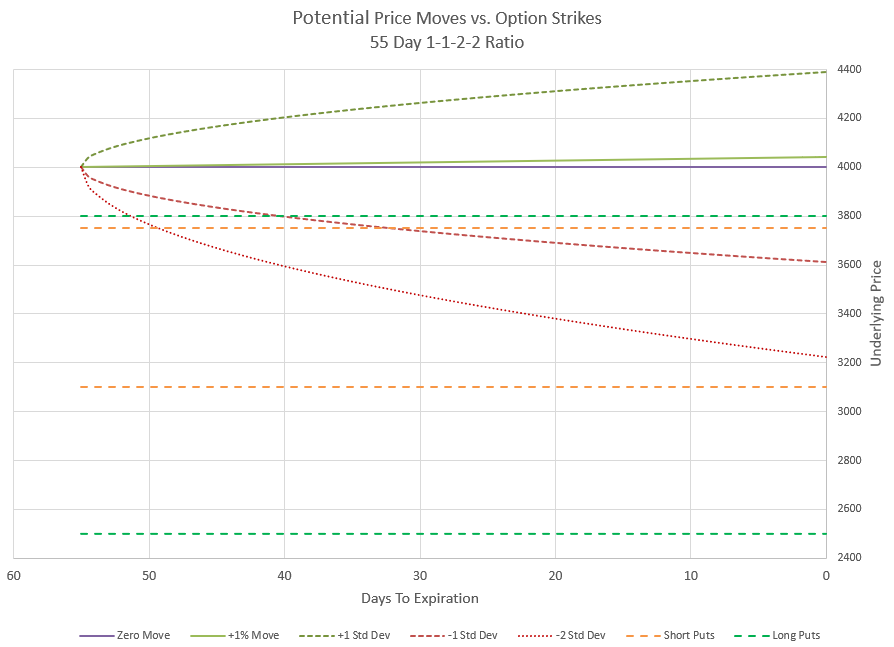

Looking at 1-1-2 values over time at the same price moves that we looked at for the expected move multiples, we can see that the premium changes are fairly dramatic and more positive as expiration approaches if the market is down.

Initially, this position collected $11.45 in premium, so we start with a negative or short value of -11.45. From there the price moves shown in the previous chart drive the premium up or down along with time decay. If price is flat or going up, premium decays and moves quickly toward zero premium. If the price goes down, the positive Delta pushes premium to more negative values. The price move of negative two expected moves really does a number on our premium initially, driving it down to below -40.

But, remember our profit chart at expiration? The flat and positive moves end up with a profit of our initial premium (all the puts have zero value at expiration, and the negative expected move and negative double expected move end up at maximum profit. Since our debit spread is 50 points wide, the negative moves would leave it fully in the money for a premium value of +50 points. And that’s in addition to the initial premium collected to open the trade. The challenge is that to get that max profit, we likely will have points in time where our position loses money.

The probability of getting to max profit is low because it would require a price drop between 6 and 22%. Based on our put strike Deltas we can estimate that we have about a 20% chance of that. Most of the other 80% is expiring with all strikes out of the money. So, it might be wise to zoom in and understand what happens with the vast majority of trades.

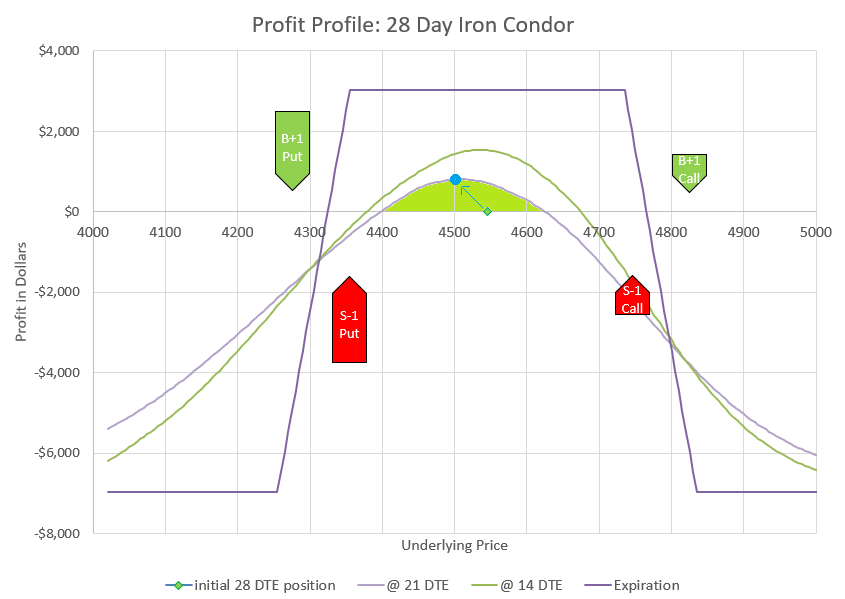

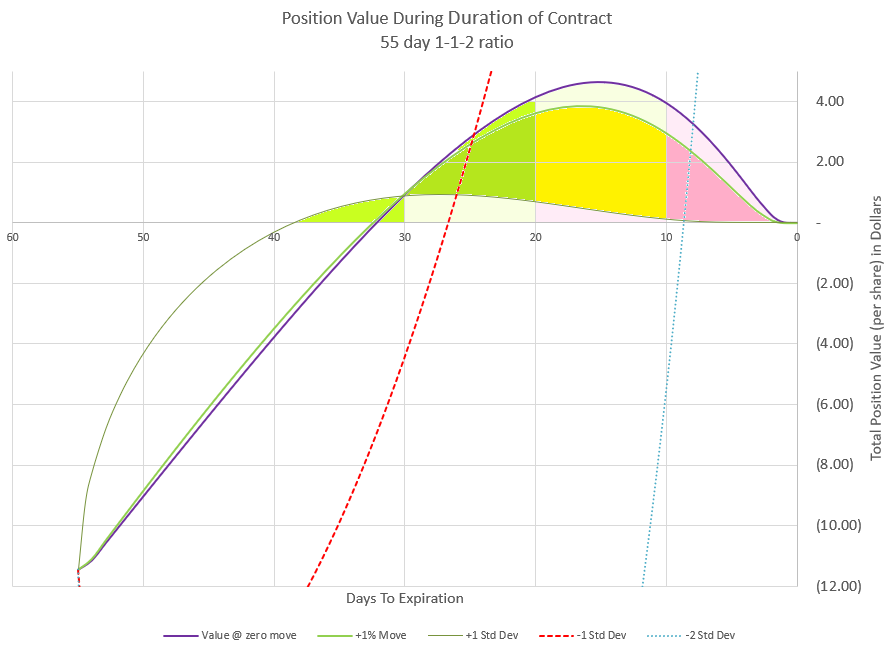

If we zoom in on the likely outcomes with the market being flat to up, we see that premium behaves very uniquely during the life of the trade.

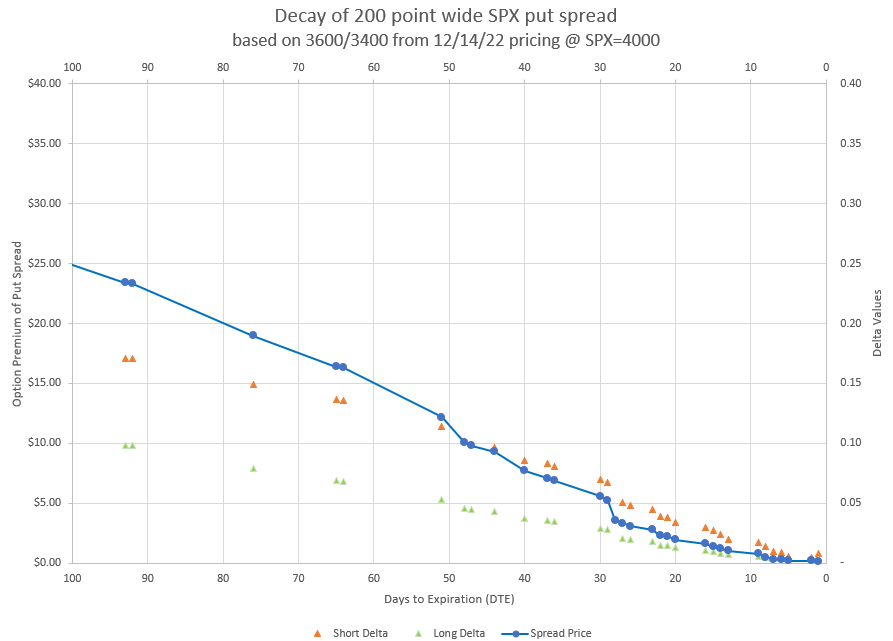

If price goes up or drops less than 200 points, we can keep our initial premium at expiration. We may be able to collect more. The profit curve at 14 DTE is actually above the expiration profit if the price remains the same. How is this possible? Because the 1-1 debit put spread decays slower than the 2 naked low Delta puts, eventually the 1-1 part is worth more than the -2 part, even though the -2 part started out with twice the value of the 1-1.

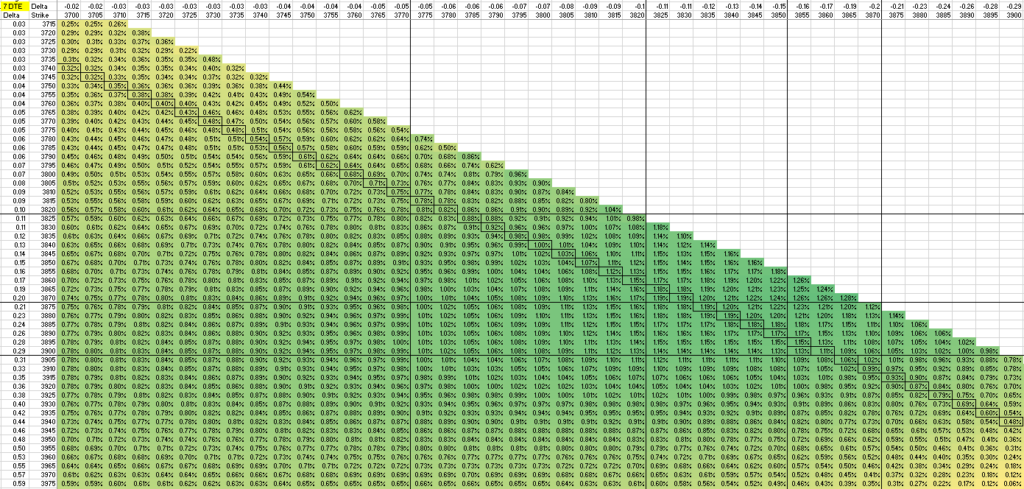

I used this chart as the featured image of this post because I thought it best illustrates how this trade plays out most of the time. If you remember when we discussed the Greeks, I pointed out that Theta is very high compared to the premium. From this chart we see that if price stays the same or is slightly up, premium will decay to zero by 32 DTE, or just 23 days into the trade. This is an example that Theta isn’t 100% accurate by itself as it looked like 12 days of Theta should move us to zero value. From the chart you can see that the curve is fairly consistent for no underlying price movement as the value of the 1-1-2 position approaches zero, but still we have very rapid decay that I don’t think anyone can complain about.

Like all ratio style trades we have discussed, this trade has the possibility of switching from negative to positive premium. The difference with this trade is that it is actually quite likely, and as such we need to plan for it and manage our profit accordingly.

I’ve colored in the area under our three flat-to-positive curves with three zones each. There is a green zone where positive premium is growing, a yellow zone where premium is topping out, and a red zone where positive premium is being lost. Notice that the curve of the 1% up move and no price move are fairly close together, and that’s because the price movement is relatively close to the same compared to the other moves we are analyzing.

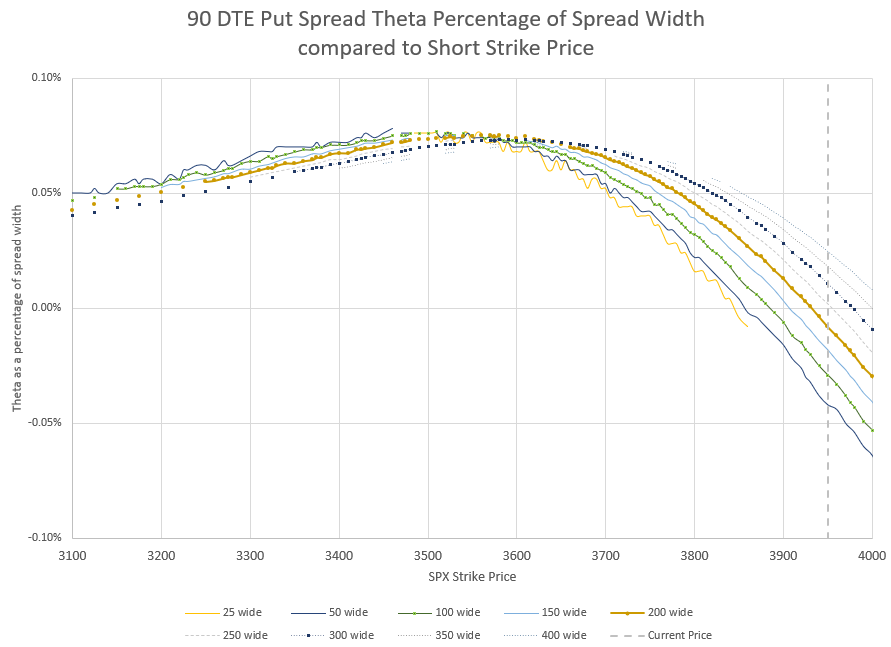

Let’s review how this happens. This trade essentially has two components, a slow decaying debit spread (1-1), and a fast decaying pair of deep out of the money naked puts (-2). The two naked puts decay faster because they are way farther out from the money, and have twice the value to start with than the debit spread. All these factors help decay happen more quickly. As long as the price stays fairly stable, this relationship will hold. Theta will be the primary driver of the premium value, and the low Delta naked puts will get to be worth less than the narrow debit spread.

The most likely scenario is that we stay inside the expected move and travel somewhere close to the no price move or 1% up move. Let’s realize that the market doesn’t move in equal amounts every day like this chart, so think of it as a smoothed out version of what premium would do. In the real world, premium would bounce up and down with price. However, if our price is close to where we started with 20 days until expiration, we would expect that the premium switch to positive has about maxed out, and it is probably a good time to close out the trade. Hopefully,your trading platform has a analysis feature that lets you look at your position and see how profits are changing day by day to help determine when the position is as high as it can go.

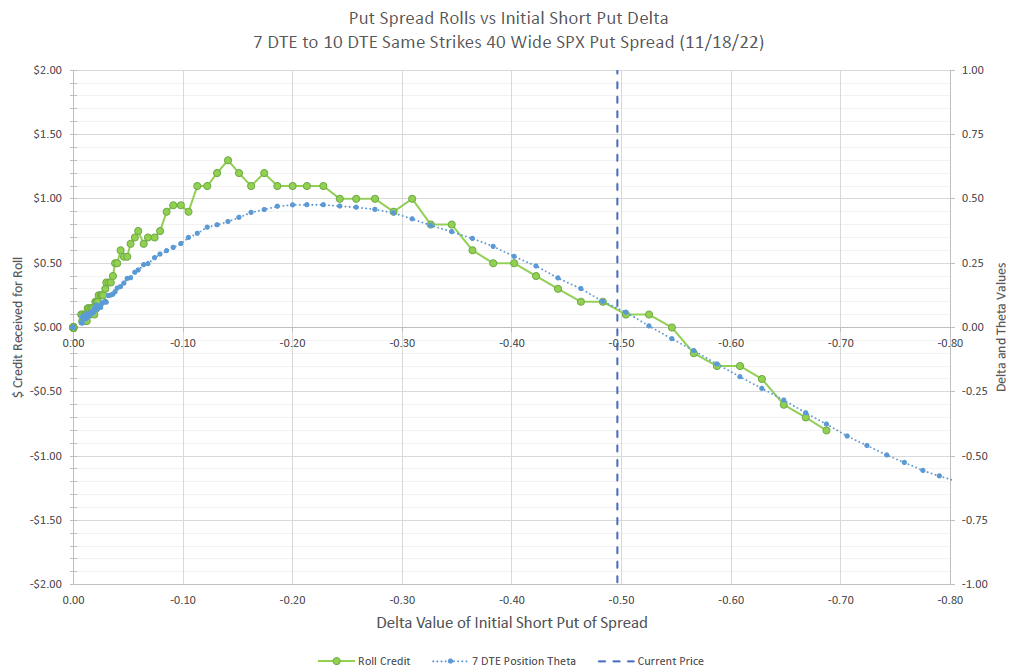

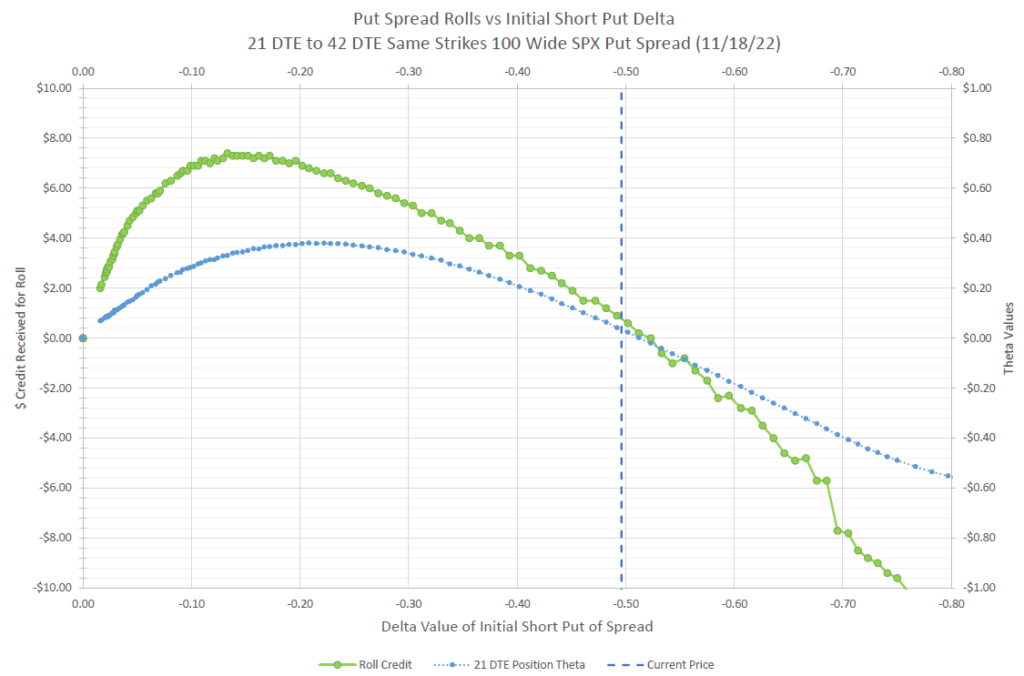

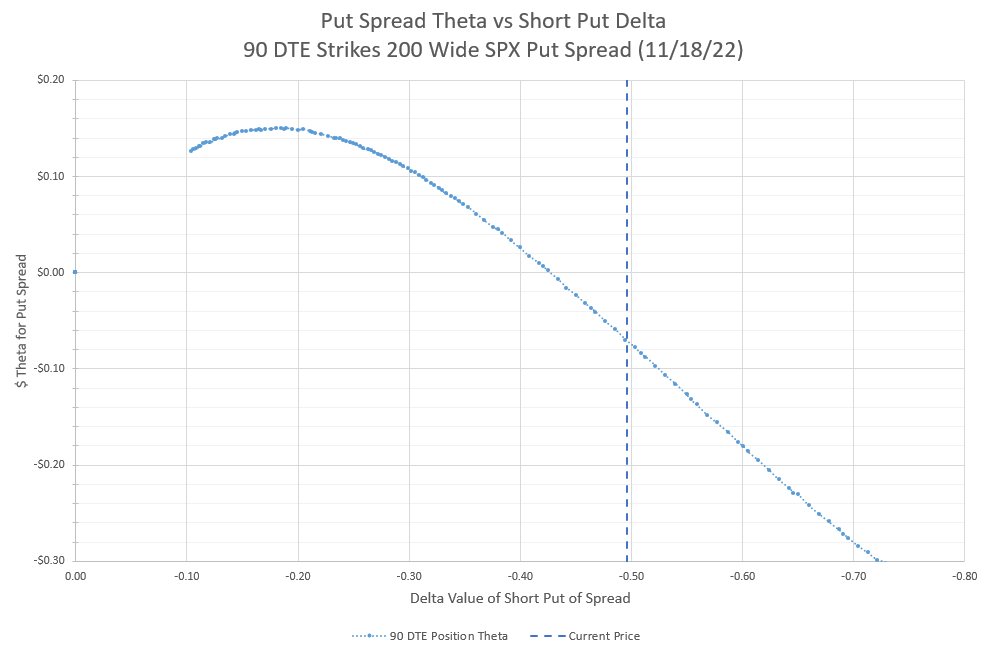

Without a chart, another way to determine how close the trade is to switching direction is to watch the position Theta. At the beginning of this trade, Theta was 0.942, or $94.16 for the full contract per day. As the trade progresses, Theta will decrease and at some point when the premium goes positive, Theta will turn from positive to negative. As it gets close to zero, that is the peak premium value. I generally try to exit the trade a few days before Theta is projected to turn negative. A big up day for the market could quickly change my very positive premium to not as positive premium, so it isn’t a time to get greedy.

So that brings us to the curve for the positive expected move. This is the curve that assumes that the price follows the one standard deviation move up. The good news when this happens is that premium decays very quickly because Delta and Theta team up. The not so good news is because the price move gets so far away from the strikes, the total position won’t get to a very high positive value. This is because all the options will drop in value quickly, approaching zero, and the upper debit spread won’t have much value. A big move up means that the probability of any of the strikes going into the money will be very low, so there is very little premium. As a result, it is likely we won’t be able to get out for much positive premium if any at all, but we will be able to keep most, if not all the premium from the opening trade. This is the least stressful outcome of the trade. If the price moves up faster than the expected move, premium will likely drop to very close to zero and may not ever go positive. So, if price is up a lot and the trade can be closed for a credit, I take the money and run. I’m happy to have a quick, winning trade.

As the trade progresses another helpful element is that Delta tends to reduce to zero or even become negative as time goes on if the underlying price stays close to flat. If a trader adds on many of these trades with different expirations, the overall position tends to be fairly low Delta and trades that have been in place for a while can buffer more recent positions. This is true until a really big move down hits and tests the naked puts. Then Delta grows quickly making losses pile up quickly as down moves continue.

The risky negative outcomes of the 1-1-2 trade

Looking at the position vs time value chart, there are two lines that represent what happens if price goes down. One is the move down one expected move and the other is down two expected moves. Interestingly, in this example, both end up at max profit by the end of the trade. So, it would appear that the trade can’t lose, which is far from true. Notice that these premium values may go very negative if prices drop quickly after opening the trade. This is because the narrow debit spread doesn’t pick up as much value from increasing delta as the wide credit spread does in a down move. We know that if price stays above our credit spread short strike at expiration, we will make money, but when price moves quickly down, it isn’t clear that price will level off.

So, as a trader, we are left with a choice when the market drops, We can take a loss and get out of the trade, or wait to see if the market quits dropping before it tests or violates the credit spread strikes. If we are a week or two into the trade, a decent down move will not make a huge impact, but initially the trade can take a big hit from a down move. The longer we are into the trade without a big down move in price, the less the risk is of a loss. On the flip side, a big move down opens the possibility of additional big down moves that can lead to a very big loss. We reviewed the odds earlier- about 4% of the time the trade will lose based on the far short puts having an initial Delta of 4. If this trade is done enough times, there will be some losses. Let’s look at some management actions that could be taken.

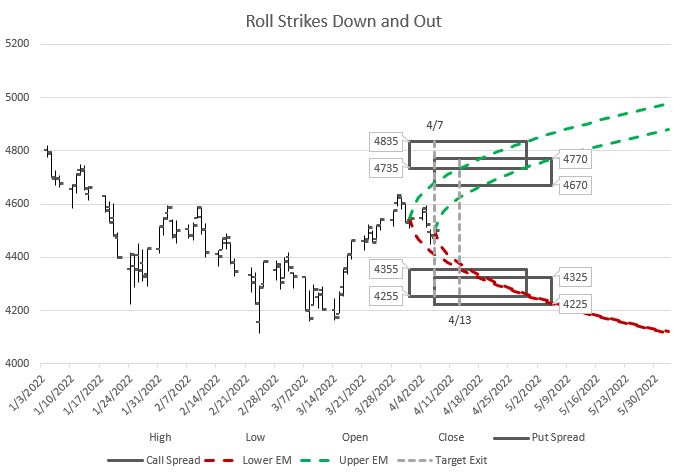

1. Set a stop based on premium price. In this example, we collected just over $11 premium to open the trade. So, we could set a stop to avoid losing twice ($22) or maybe even three times ($33) our initial premium. This would mean a stop loss if premium climbs to $33 or $44, given that $11 premium is our starting break-even point. This is the simplest risk mitigation strategy. Using this will lower the overall win rate as many negative scenarios would end up fine if not closed, but this management technique will prevent huge losses that might impact the account dramatically.

2. Close the trade if the underlying price goes below a trigger point. We know this trade has a lot of cushion. We can handle much more than one expected move and be profitable. But if the move is much more than expected, we have to consider that the move is very unusual and dangerous for us. Perhaps our point to get out is when the debit spread is in the money, or when we are half-way between the debit spread and two naked puts. Or maybe it is the strike of the short naked puts that is the final trigger to get out. The further down we allow price to go down, the more we stand to lose. Pick the underlying price where it gets too uncomfortable and use that as the trigger point to get out of the trade.

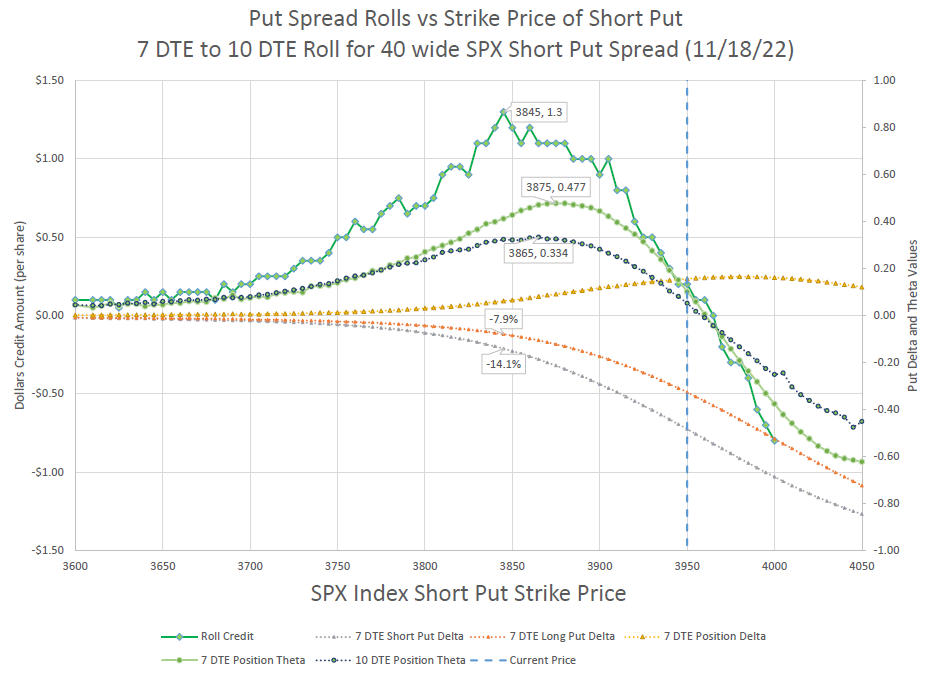

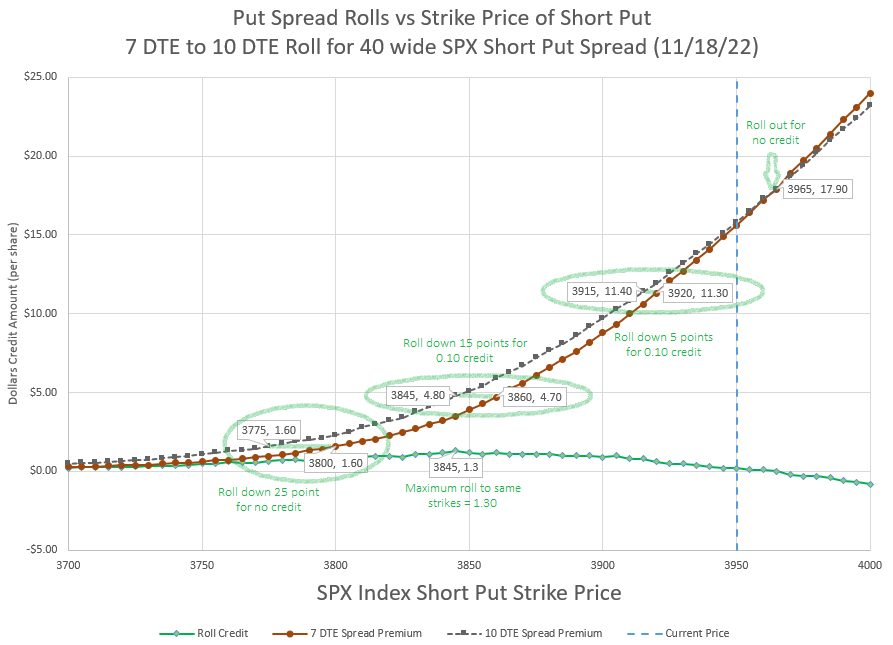

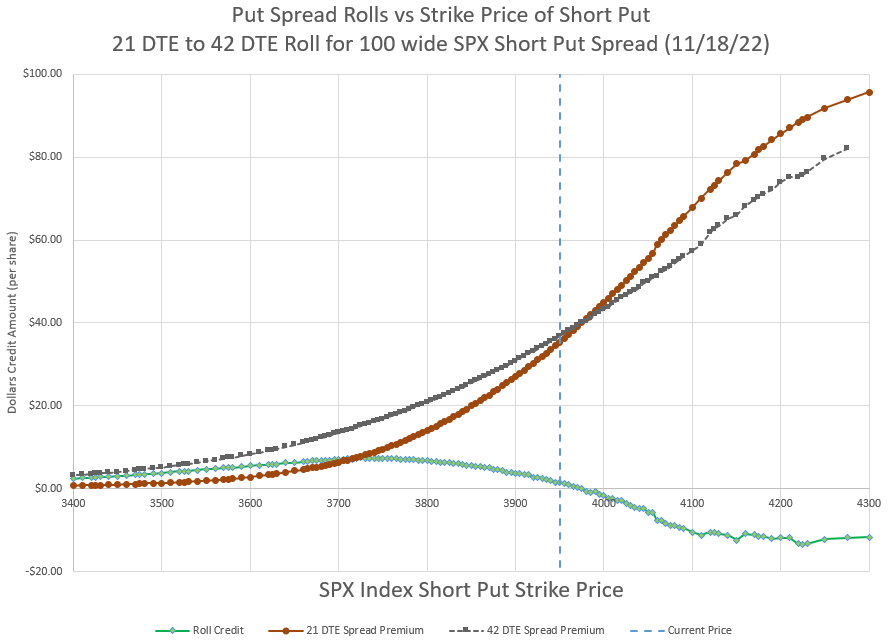

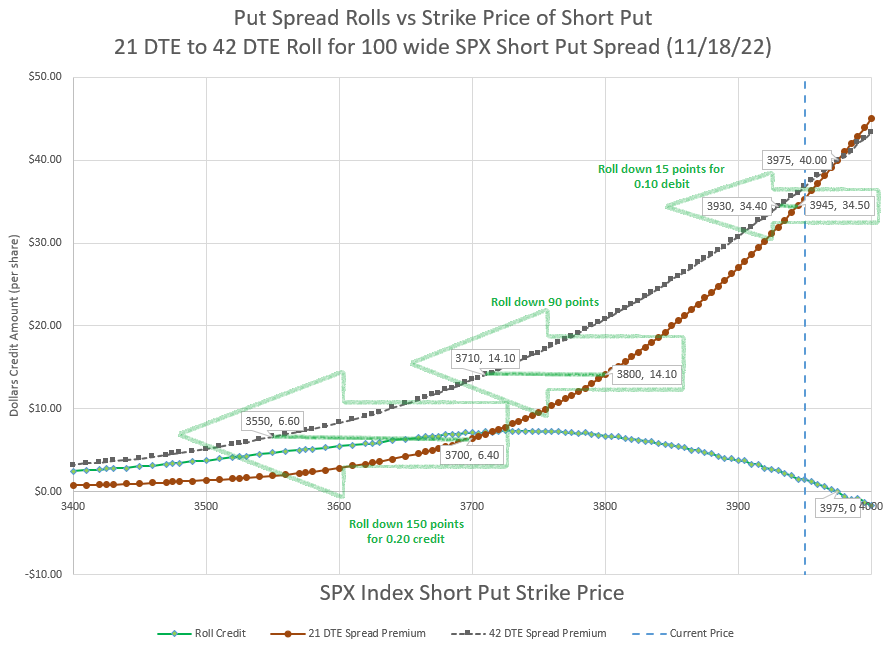

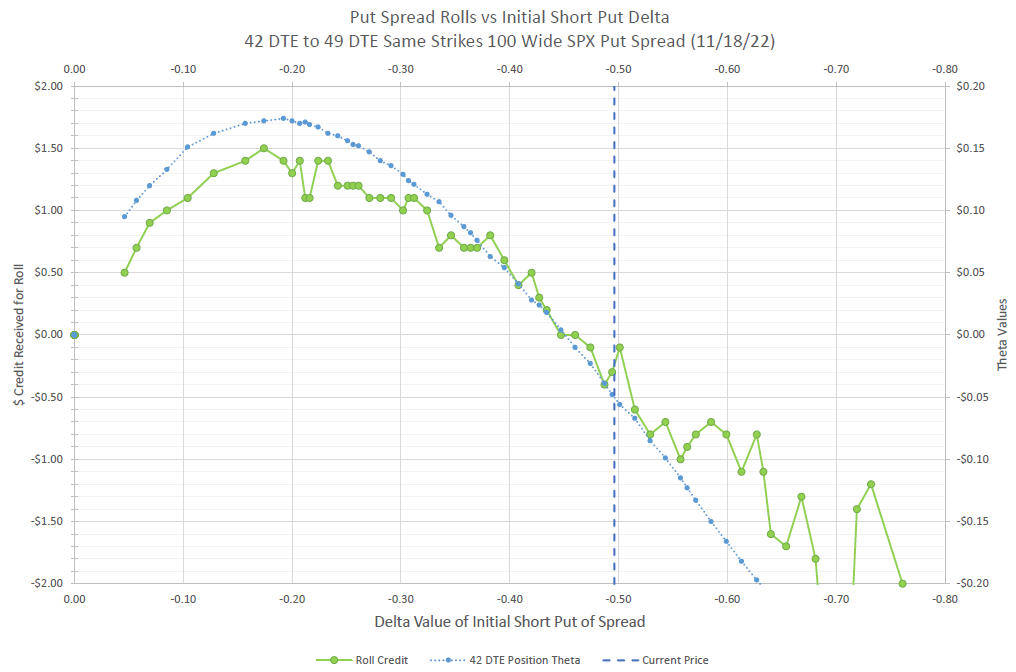

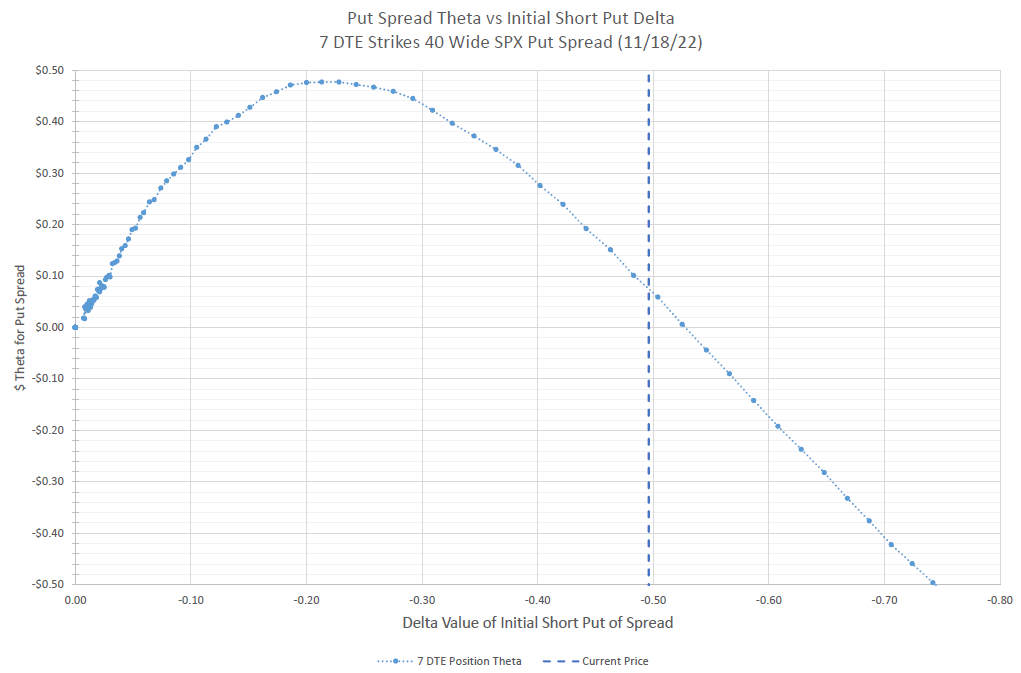

3. Roll out in time if premium or price triggers are hit. If the position is rolled, it can be rolled out for a credit. This gives more time for the market to turn around. However, it gives more time for a losing trader to lose more, because we likely can’t roll down much lower and still get a credit, and we will likely have to pay to roll the debit spread. If the price move continues down, there will be much less room to maneuver going forward.

4. Simply hold on and hope the probabilities play out. With 55 days in the trade, we just need to move down less that two expected moves by expiration. If the capital is available, and the conviction is there, holding can bring max profit with a big down move. Note that as time passes and the naked puts stay out of the money, the premium has to go away, so the value can evaporate very quickly with very high Theta as expiration approaches. This can be observed in the value vs time graph for the -2 EM curve. It can also result in a very large loss. As expiration approaches, the difference between max profit and a much bigger loss is just a few percentage points of price movement and the potential loss is much more than max profit.

In this example we can see that a move down of one expected move really doesn’t challenge our position, while two times the expected move is playing with fire. So, one approach might be to hold as long as the move stays within the expected move to the downside and switch to closing or rolling once the move exceeds that or some other multiple of expected moves. In any case, a trader has to know their risk tolerance and have a management plan for both winning and losing trades.

What about calls?

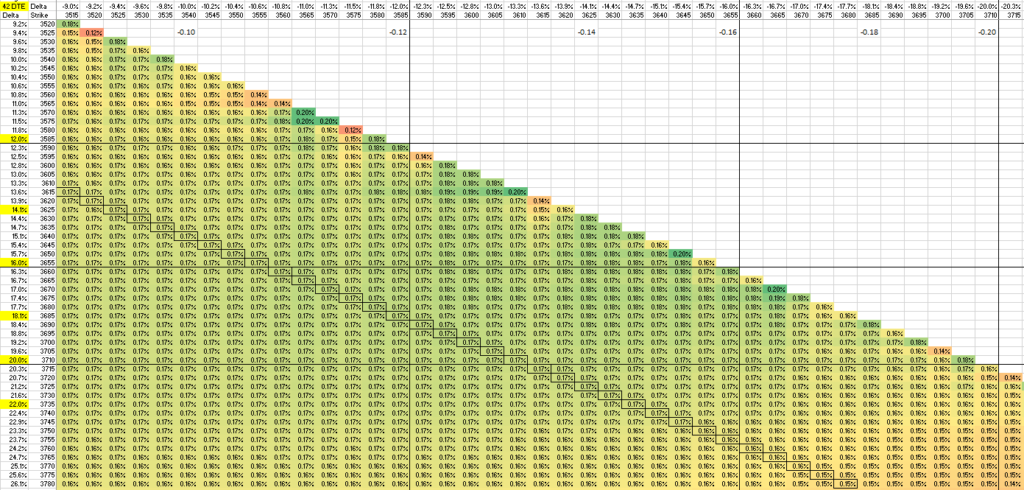

A logical question might be- if this works so great for puts, why not double up and do it for calls as well? Well, there’s one problem- skew. On indexes implied volatility is higher as strikes go to lower values and declines for higher strike prices. As a result, out of the money puts have higher implied volatility than out of the money calls. More importantly, far out of the money puts have higher implied volatility than puts closer to the money.

Look at our setup for this example. Implied volatility of the single long put is around 25, while the two short puts have implied volatility of 39. This helps two ways. The short puts have more of their premium tied to volatility, bumping up their price compared to the long put. Also, the higher implied volatility pushes the strike price further down to get a matching premium to the debit spread, making the trade a higher probability of success. We are selling more of the higher implied volatility and buying lower implied volatility, a key reason to use front ratio spreads.

A similar setup for a 1-1-2 call trade would reverse the dynamics. The long call closest to the money would have the highest implied volatility and the two short calls would have the lowest. To collect similar amounts to the put trade, the call strikes would be much closer between the debit spread and credit spread, and the difference in the deltas of the strikes would also be closer together, meaning a narrower window of max profit, and a higher probability of max loss. While still a trade with positive probability, it generally isn’t as attractive as the put side.

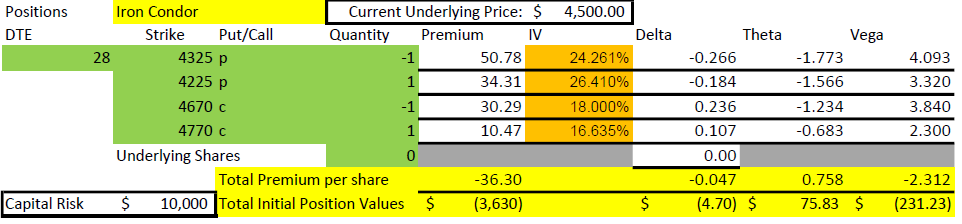

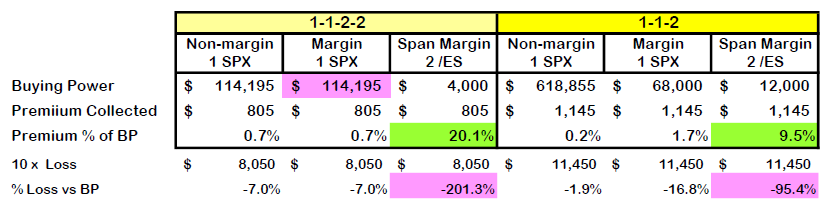

Buying power requirements for 1-1-2

I usually don’t spend much time talking about buying power because most trades I do are defined risk credit trades where the amount collected is a significant portion of the capital at risk. This trade is not so much, as it is a naked ratio spread (1-1-2). In non-margin accounts, we collect 0.2%, which isn’t much.

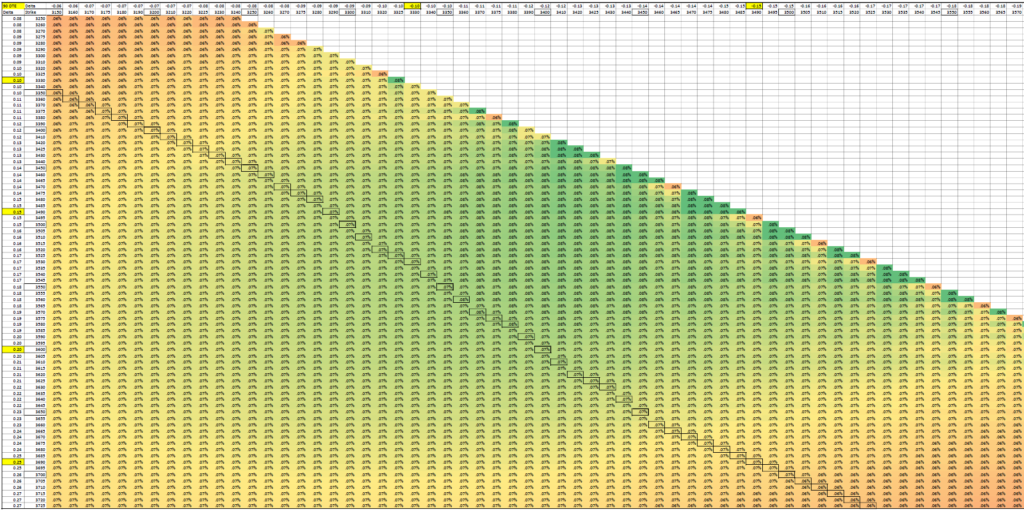

Below is an analysis of different possible ways to trade. I looked at trading each of these strategies three different ways. First, I looked at a cash secured account, like a retirement account. Next, I looked at an account with margin for naked options. Finally, I looked at a much different approach, trading futures options with span margin. The margin and span margin amounts came from entering this trade into the tastytrade trading platform. I’m also showing the defined risk 1-1-2-2 version for comparison as well.

I highlighted some key takeaway points. First, is how leveraged span margin with futures options can be for this trade. Our most capital efficient trade would be doing the 1-1-2-2 on futures span margin where we would collect 100 times the premium as a percentage of buying power (20%) than the non-margin account of the 1-1-2 trade (0.2%). Of course, with leverage comes much more risk. I chose to consider a loss of 10 times the initial credit as a practical worst-case scenario. The span margin would end up costing huge amounts more in a disaster and could potentially wipe out an account if the trade used a high percentage of the account’s capital. Span margin isn’t static, when a trade moves against a position, the span margin is re-calculated and the requirements can quickly explode in a big market move.

A couple of weird margin anomalies to point out. In my margin account, the defined risk 1-1-2-2 trade required almost twice the buying power as the undefined 1-1-2, which is weird because clearly there is more risk in the naked 1-1-2. I think it may be that the calculation for defined risk is normally much less than undefined and the software may just assume that margin is not useful in defined risk. On the other hand, defining the risk on the futures version cut the buying power by 1/3. Different brokers may calculate their margin requirements differently, so don’t take this as universal truth. Similarly, remember that while defining risk usually increases the return on capital, it makes outsize losses more likely, especially when scaling up. Notice that the highly leveraged futures 1-1-2-2 would lose twice as much as a percentage of capital that the futures 1-1-2 setup in a 10x loss. I discussed this phenomenon in detail in my post on comparing risk.

Remember that margin and span margin change as the trade progresses depending on the market behavior. Span margin is subject to big swings when prices go against a position. A broker may force a position to close much earlier than a trader would want to get out due to expanding capital requirements. So, while initially the position is cheap to enter, a trader needs to limit each position to a fraction of the overall account size.

But the good side of this is that this trade can be entered for a very small cost. The trade is very high probability. We can also make more than the premium collected. I didn’t include it in the chart, but maximum profit for the most leveraged choice above would be $5,805 profit on $4,000 buying power, a return on capital of 145%. And there is over a 20% probability of that happening.

One final note on the buying power analysis table. To keep the quantities an apples-to-apples comparison, I used double the number of /ES futures options because futures options only control half as much value as SPX index options. So, technically, those futures options trades listed are 2-2-4-4 and 2-2-4 because they use twice the number of contracts to get the same notional exposure. I reviewed differences between index options and futures options in detail in my post about different ways to trade options on the S&P 500 index.

What about small accounts?

Readers looking at this may be thinking, “Gee, this is great for multi-millionaires, but what if the account is too small to consider any of these buying powers?” Great question- there are other alternatives. First off, a trader could use half the buying power listed by just trading options on one contract of the Mini S&P 500 futures (/ES). The 1-1-2 example would only take $6,000 buying power for $572 premium received. But, if that is still too much, we can make it a lot less.

Many traders are more familiar with options on the SPY exchange traded fund, which trades at approximately 1/10 the value of the S&P 500 index. For futures options, there is also options on the Micro S&P 500 futures contract (/MES), equal to 1/10 of the /ES contract size, or 1/20 of the size of an SPX option. By using SPY or /MES, we cut the size of the trade down by 1/10 compared to the above table. If the account is taxable, another choice would be the $XSP index, a 1/10 value index of the S&P 500 with favorable tax treatment, but much lower liquidity with few options that far out in time. Again, all these alternative versions of S&P 500 options are discussed in my post on different S&P 500 choices.

So, for an account with futures trading capability, this trade could use /MES futures options and get into the 1-1-2 trade for just $600 buying power. An account with options margin could use SPY or $XSP and get into the 1-1-2 trade for $6,800 buying power. A trader doesn’t need a million dollar amount to trade this.

Concluding thoughts on 1-1-2 trades

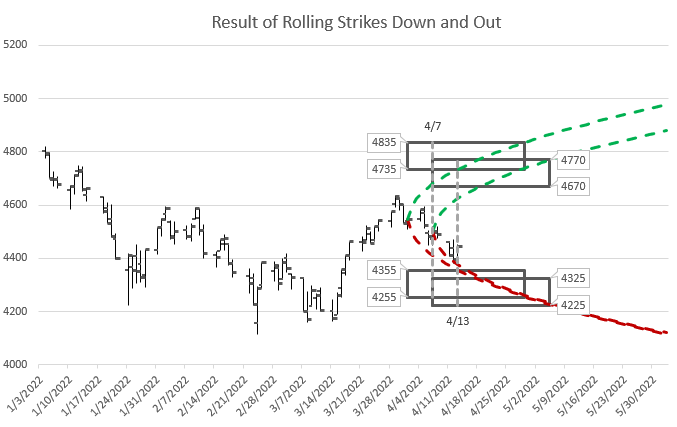

I know a number of people who have traded versions of this trade during the bear market of 2022 without any issues. One trader I follow and interact with had one of their best years in 2022 because of this trade and the bear market that moved the market down, but not fast enough to ever drive the naked puts into the money. In fact, it could be argued that this trade, like most trades that collect credits from selling puts, works best if entering when the market is already down and implied volatility is high. Bad scenarios are already priced into option premium and there is a lot of cushion between strikes. This trade is most dangerous when volatility is low and prices are high- the probabilities are not as good, because a move of more than two times the expected move down is not nearly as far.

While not for everyone, the 1-1-2 trade provide a very high probability of success with a nice payout when used with leverage. The trade requires monitoring to maximize profit and to prevent catastrophic loss, so it really is not a set it and forget it trade. The key is to have a plan to manage the position if the market goes against the trade and stick to the plan.

For real life results of this trade, see this more recent post on 1-1-2 trades in the first half of 2024.